Growing up, road trips were a fairly common phenomenon. My parents and I would usually drive at least once a year between Chicago and Kansas City, and vice versa after we moved from the Windy City to the City of Fountains. In the 2000s we’d fairly often make the 3.5 to 4 hour drive east from Kansas City to St. Louis, and every summer in the first half of the 2000s we would drive across the Great Plains for a weeklong vacation at a dude ranch up in the Colorado Rockies. Road trips, then, were a pretty regular sort of thing to do.

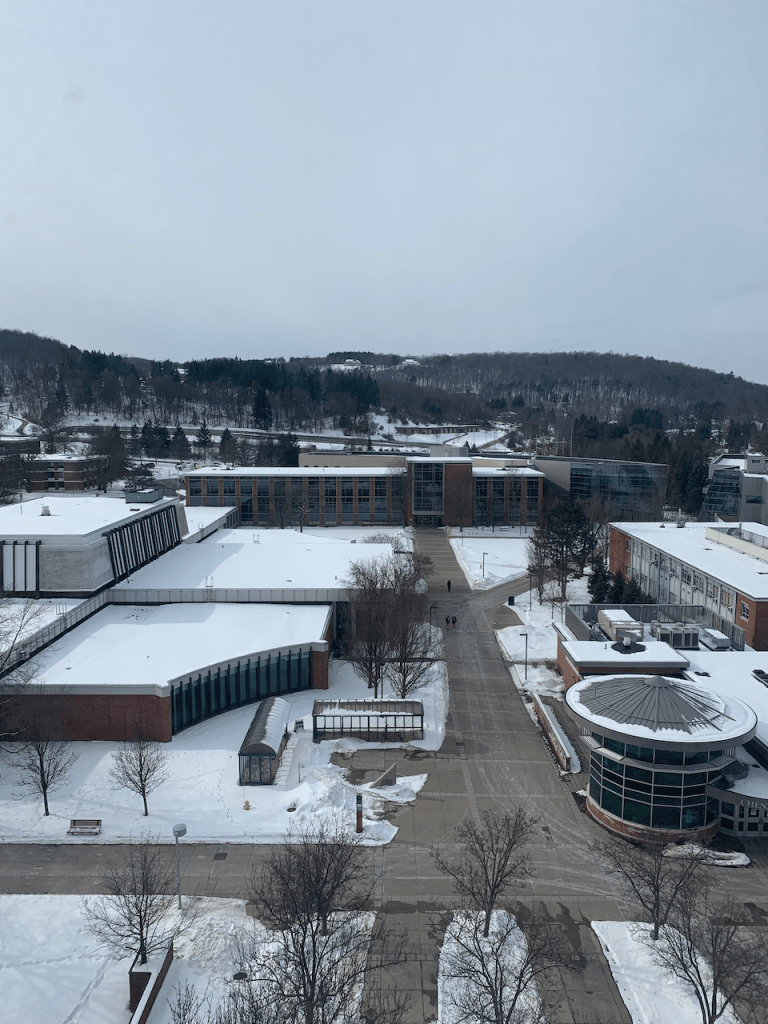

However, in the last decade or so, our adventures beyond Kansas City have tended to be less on the highway and more on the rails or in the skies. It got to a point that the few road trips I’d end up doing would be rare instances that would increasingly become frustrating for how long they seemed to take. So, in February 2019 when I got accepted into the History PhD program at SUNY Binghamton in the rolling hills of New York’s Southern Tier, I knew immediately looking at the map that I’d have to make at least a couple road trips just to get there and back again.

Endurance

The thing is, as long as a 7.5 to 8 hour drive to Chicago or a 9 to 10 hour drive to Denver might seem, any drive to Binghamton was going to steamroll past those regional drives. Binghamton is 1,000 miles (1,609 km) as the crow flies from Kansas City, and on the road, the trip can be anywhere from 1,100 miles (1,770 km) to 1,500 miles (2,414 km) in length. This usually means that in full the drive itself will take between 18 and 21 hours, which itself requires an overnight stop. For me, when I was first sketching out how I was going to make these long drives, it was clear from the first moment that this was no small undertaking.

A transcontinental drive on any continent is something to be proud of. It requires a lot of planning, a good knowledge of your own endurance, of your car’s capabilities, and of the regions you’re going to be driving through. At the time of writing, it’s only just becoming possible to make such a drive in an electric car, meaning that most such road trips are going to be producing their own carbon footprint. I haven’t calculated exactly how much CO2 I’ve produced so far on these, but that is one big problem with road tripping that I’d like to resolve. Beyond the things you can control, before going on any such road trip you have to bear in mind the road conditions themselves.

In the next few days, the Biden-Harris Administration is supposed to be announcing a $2 trillion infrastructure plan as a part of their American Rescue Plan. The plan covers a wide range of different initiatives, all of which badly need more funding. Road repair is one such initiative, and trust me when I say the roads in many parts of the US that I’ve driven through need help. There are a number of places along the routes I use between Kansas City and Binghamton that have been so badly potholed and worn down that you have to be constantly vigilant for trouble. There’s even a stretch of I-88 in New York (not the same interstate as the tollway in Illinois) that has permanent signage warning drivers “Rough Road” ahead. Whoever is driving at any given moment can’t take their eyes off the road for a second, because you never know what could happen next.

Weather

Another big issue to keep in mind is the weather. I usually will start monitoring weather forecasts in a couple of key cities I usually go through about a week before my planned departure date. Covering all the possible routes, these cities are Binghamton, NY; Erie, PA; Scranton, PA; Harrisburg, PA; Pittsburgh, PA; Columbus, OH; Indianapolis, IN; Chicago, IL; St. Louis, MO; and Kansas City, MO.

In the winter months (October to April) if there’s any chance of lake effect snow along Lakes Erie and Michigan, I’ll reroute further south, staying on I-70 after Columbus and eventually taking the Pennsylvania Turnpike to Harrisburg, PA before turning north on I-81 towards Binghamton. If there’s also really bad snow in the Appalachians in Pennsylvania, and lake effect snow in Chicago, Cleveland, or Erie, I might end up postponing the trip for a day or two to let the weather calm down again. In January 2020, midway through my long drive east I got caught up in a whiteout blizzard on US-22 east of Pittsburgh (you can read more about that here) in the predawn hours of that Sunday morning.

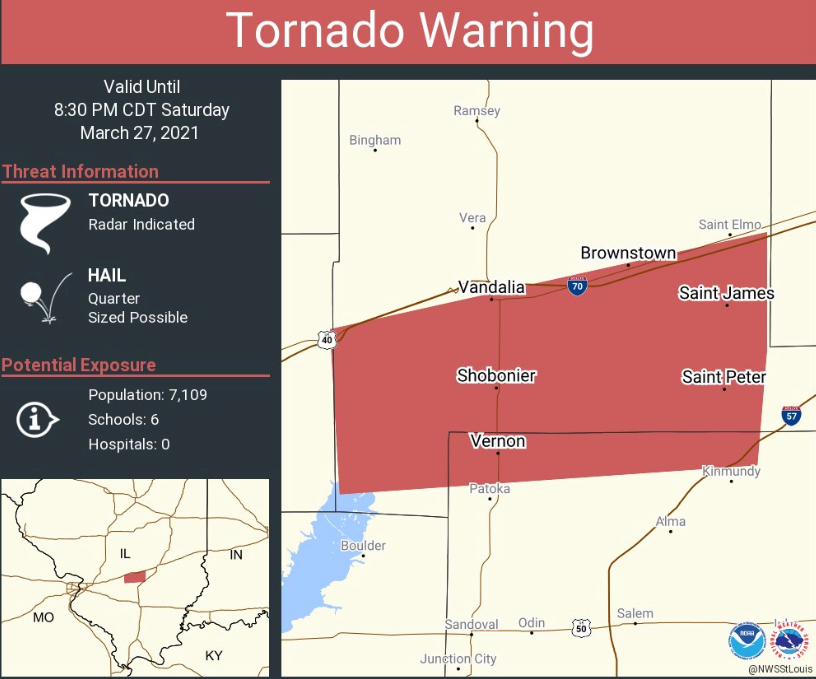

Snow and ice are worse problems for driving than rain is during the rest of the year. I’ve been lucky a couple of times. In August 2020 I had a near miss of a big derecho that wrecked widespread damage across Iowa, Illinois, and Indiana. I could actually see it off in the distance in my rear-view mirror when I was getting dinner in Indianapolis. And on day 1 of this most recent long drive west, 27 March 2021, I was less lucky with my timing, and drove right into a powerful thunderstorm with reported tornado activity between Mulberry Grove and Highland, IL.

As terrifying as the January 2002 blizzard in the Pennsylvania mountains was, this thunderstorm was worse. I made it out okay, with only 15 minutes added onto the total drive time, but to quote my favorite Lando Calrissian line from Return of the Jedi, “that was too close.”1 It was reminiscent of my first time doing a cross-country drive in August 2009 when on the way back from Dubuque, IA I was at the wheel when my parents and I hit a powerful late-summer thunderstorm an hour east of Des Moines. We ended up pulling over in Altoona, IA at a Culver’s until the storm passed.

Entertainment

When I was still too young to drive, and kept my place in the back seat of whichever car my parents owned at the time, I often found various ways to keep myself entertained. Among those that I haven’t carried over into my current long drives are watching movies on DVD. We had a screen and DVD player that could be strapped to the back of the front passenger seat’s head rest with velcro. As a driver, it’s not safe to be looking at much of anything besides the road. As I’ve gotten older I’ve found that I tend to get motion sickness whenever I try to read in the car, so on the rare occasions when I’m a passenger these days, that’s out of the question. Instead, the tried and true classic remains satellite radio, music, and audiobooks.

Generally, my first choice will be to listen to a good long audiobook, something that will keep me awake the entire way, a true page-turner. In the first two years of these drives to and from Binghamton, I’d listen to a lot of Star Wars books on Audible, which were usually action packed and entertaining enough to keep me going. On the most recent pair of drives (January and March 2021), I’ve been listening to President Obama’s new memoir A Promised Land. It’s a really fascinating book to listen to, narrated by the guy himself even, but as much as I enjoy hearing about economic or foreign policy (and I’m not being sarcastic there), after a couple hours on this most recent drive I noticed I was starting to get tired of it. So, at that point I’d switch over to what I call my “stay awake” playlists: a good combination of ABBA, Elton John, and more recently Hamilton.

I first compiled that particular playlist in the preparation for a 2 am departure from Binghamton to make a 5 am flight out of Wilkes Barre/Scranton Airport an hour south of Bing in NE Pennsylvania. It’s been especially helpful on the nighttime legs of my long drives, and formed much of the soundtrack for the last 2 hours of Day 1 of my most recent Long Drive West, and a good portion of the predawn hour of the drive on Day 2. On other occasions, like a shorter road trip I took in my first couple weeks after moving to Binghamton in August 2019, I’ll switch to satellite radio and listen to NPR, the BBC World Service, or maybe catch the Cubs, Royals, or Sporting KC if they’re on. As much as I want to listen to whatever it is I’m playing, the primary goal of that audio is to keep me awake and going. And, if all else fails, and I know it’s a good time, I’ll call my parents or a couple of really close friends to chat for 15 or 20 minutes.

Conclusion

Looking ahead, I anticipate I’ll continue to make these long drives at least until I’ve finished my PhD in Binghamton and to wherever my next job takes me. The COVID Pandemic has only heightened the need for these road trips, with most other modes of travel not really being as safe as I’d like in the last year or so. My original plan when I left for Binghamton in 2019 was to make these long drives at most four times per year: on either end of each semester in January, May, August, and December. The main reason for driving rather than flying or taking Amtrak is that I need the car on either end. In the future I’d gladly fly, make the trip in 4 to 8 hours instead of 18 to 21, or even take Amtrak once they’ve resumed dining car services on their transcontinental lines.

Moreover, I really want to help reduce my own carbon footprint, eventually replacing my 2014 Mazda 3 with an electric car, maybe in about 4 or 5 years. By then though, hopefully I’ll be in a situation where either I’ll be working here in Kansas City again and won’t need to drive cross-country to see my family, or I’ll be in a city with a strong enough public transit system that I won’t need to worry about having the car in one place or another like I do now.

All of that said, these road trips are fun. They’re adventures pure and simple. I never really know what’s going to happen on the road or on the stops I make along the way. In November 2019, I reached what I’d call a pretty special milestone when I drove my Mazda to within sight of the New York skyline and the Atlantic Ocean beyond. I cheered, I, a guy from flyover country, from the middle of the continent, had driven to the ocean. One of these days, I’ll complete the entire transcontinental drive, make it to the Golden Gate, and maybe even drive down the Pacific Coast Highway. On its own, the bragging rights involved, to be able to say that I’ve driven the same car from Atlantic to Pacific will be worth the trip.

Notes

1 Someone should really make a GIF of that particular line. I’ve been looking for one for a couple years now.

Corrections

Amended 1 April 2021 to reflect a more accurate dollar amount for the Administration’s Infrastructure Bill.