This is a rare blog post that deals directly with my day job. For those of you who aren’t aware, I’m currently a PhD Student in History at Binghamton University. I study sixteenth century French natural history discussing Brazil, drawing particularly from the works of André Thevet (1516–1590) and Jean de Léry (1536–1613). As such, my main primary sources are pretty straightforward: Thevet’s Les Singularitez de la France Antarctique (1557) and Cosmographie Universelle (1575) and Léry’s Histoire d’un voyage fait en la terre du Brésil (1578) form the backbone of my work. But beyond those sources is another layer of source material that those two authors used to ground their own writing. In the case of natural history, Renaissance Natural History is largely founded on Pliny’s Natural History (published 77–79 CE) and Aristotle’s works on natural philosophy and zoology, in particular his History of Animals (4th c. BCE).

Thankfully, I came into this project already fairly familiar with Pliny, having used his Natural History in a project on classical geography and the legacy of the voyages of Pytheas of Massalia (c. 350–306 BCE) in my undergrad. I’ll admit I’m less familiar with Aristotle outside of his works on ethics, but luckily for me and all other scholars there are plenty of resources available today that can give you everything from a quick citation to a thorough discussion of Aristotle. My two favorite are the Loeb Classical Library side-by-side Greek-English translations and the Perseus database provided by Tufts University. These are often the best resources I’ve found, and have in a sense made buying copies of these classical texts unnecessary, which my budget appreciates.

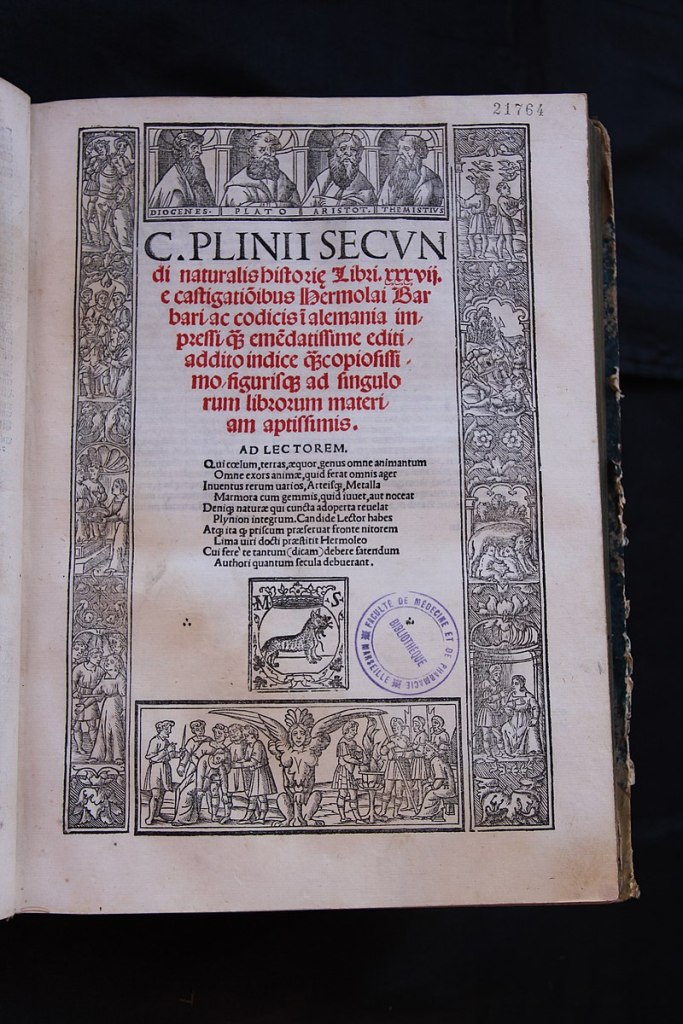

That said, in the context of Renaissance Natural History how much should I really be using these twentieth and twenty-first century editions of these classical sources? If I really want to be accurate to the period I’m writing about, I ought to be using sixteenth-century editions of both authors. The easiest and most accurate way to do this would be to figure out which editions were used by my authors and look for copies of those that have been digitized and are available online. But more often than not it’s not that easy to figure out which editions exactly were used. The secondary literature about Renaissance editions of Pliny and Aristotle provide some clues as to how the early printed editions differ from our modern edited ones, both in the original languages and in translation, but those articles and books don’t quite take the runner to home plate.

The best guide then seems to be using the examples and patterns set by other books that I know for sure were owned and read by these authors and use those to guess at which editions of Pliny and Aristotle they would most likely have known. One good lead for Thevet at least appears to be the fact that he had a connection to the court of François I (r. 1515–1547) who like Thevet came from the provincial city of Angoulême. This means if there’s a specific edition noted as being present in François I’s library, then that might be a good lead to follow to see what Thevet was reading. Looking at the nine books known to have been owned by Thevet, curiously all of them were in French, none in Latin. Generally, I’ve taken this to mean that he probably preferred to read in his native language, so he may have preferred a French translation of both Pliny and Aristotle rather than reading editions in Latin and Greek.

At the end of the day as much as I see a profound benefit in using these sixteenth-century editions of Pliny and Aristotle to really establish my research in the natural history being written in the Late Renaissance, I’m still going to keep my modern edited versions of those same classical works handy. After all, they’re much easier to search than any sixteenth-century version, so if anything the modern editions will continue to prove to be good road maps to help me navigate through their centuries old forbearers.