How Space Exploration Can Unite Us – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

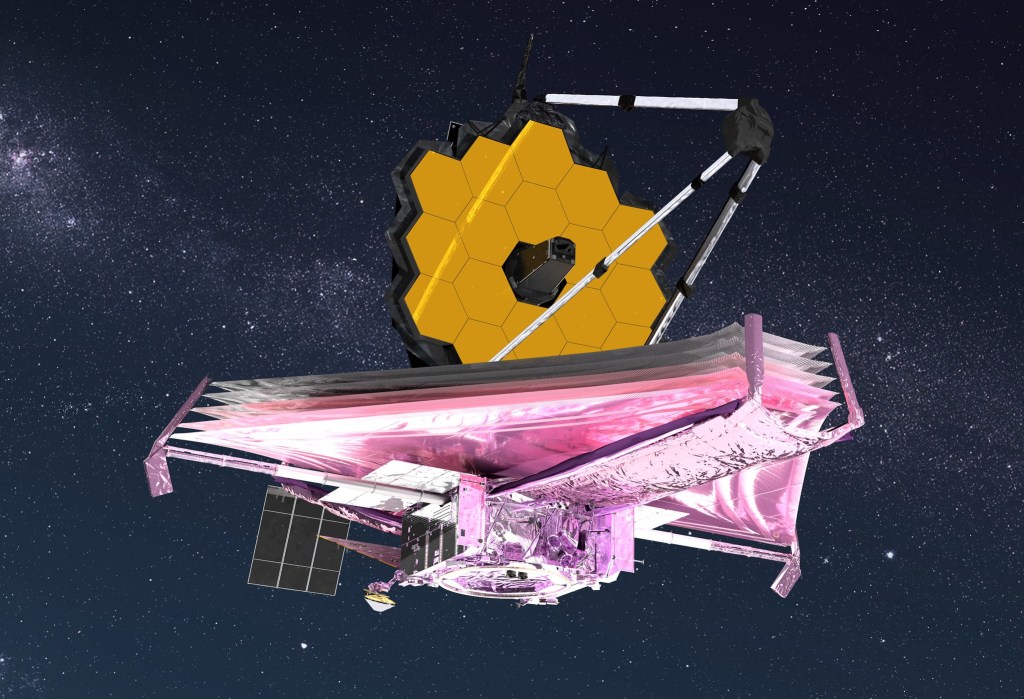

My Dad woke me up just before 6 am on Christmas morning to watch the long-anticipated launch of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) from the European Space Agency’s spaceport in French Guiana. Over the past few months, I’d heard and read a great deal about Webb, the engineering behind it, and the mission it has been sent on to travel to the Lagrange 2 point about 1 million miles, or 1.5 million kilometers, from Earth. Once there, Webb will serve as our newest set of eyes on the stars and planets far removed from our own. It will even be able to detect the chemical composition of the atmospheres of distant exoplanets, which could provide us with far better leads than ever before to finding life on distant worlds.

In this last week of 2021, during the Christmas season, a generally happy time of the year, I’ve got to admit there are a lot of problems facing us that are sure to dominate the year to come. The COVID pandemic continues and has recently flooded humanity with a new wave powered by the omicron variant, leaving us scared and worried during the holiday season. The tensions that have boiled over in the last few years in this country, social unrest born out of decades of dissatisfaction, disenchantment, and the pressures of our lives in this Second Gilded Age have brought we Americans closer to the brink than we’ve been in quite some time. Globally, we can’t bring ourselves to do enough to combat climate change, the greatest existential threat humanity has yet faced. Still, the familiar tempo of the drumbeats rises quicker and quicker as the Ukrainians prepare for a potential invasion from Russia, and tensions continue to simmer in the waters between China and Taiwan. Both of these regional wars could well draw my country, the United States, and our allies in, cycling further and further until that simmering pot comes to a boil in the form of another world war.

Meanwhile civil wars, famines, and the other children of fear torment people around the globe in nearly every country, some worse than others. The 2020s have thus far proven to be one of the darkest decades in recent memory, with many of its woes being fruits born from the troubles of the 2010s, 2000s, and the century prior.

Yet alongside all of this, I still have hope that we, humanity, will see ourselves through these threats, that somehow, someway we’ll survive as we have now for so long. It’s interesting to me how the same story, human history, can be told in so many different ways. I was brought up learning the story of human progress, of ingenuity and invention from the Promethean discovery of fire to the digital age in which we now live. It’s a story that has a happy ending, that believes we will eventually overcome our sins and the ghosts that have haunted our waking days as much as our dreams of a better tomorrow. The question I’m left with now, as an adult prone to daydreaming rather than a child without a responsibility to make something of myself, is how do we achieve that future? How do we make tomorrow better than today or all the yesterdays in our collective memory ever have been?

I suggest we look to the potential of what Webb can tell us about the Universe around us. We are after all made of stardust, as Carl Sagan was famous for saying, and at the end of the day it is to that stardust that we will return. The exploration of Space has the potential to be truly revolutionary to our story. If done right, it could be the catalyst that pushes our boulder over the hill, letting us the eternal Sisypheans we are, out of the Hadean turmoil we’ve been in for as long as we can remember. By realizing we are not alone in the Universe, that there are others out there who like us have struggled and fallen time and time again yet still found the strength within them to rise up and build civilizations in their own images, to leave legacies for others to remember them by. We have the potential to overcome our troubles: war, hunger, poverty, ignorance. Let’s set those drums aside and sit down and talk to one another, get to know one another, and learn from each other. Let’s realize that we’re more alike than different, no matter who we are, where we’re from. We may speak different languages, and by extension think in slightly different ways, we may have different incentives for our actions, but at the end of the day we’re all still human.

On the Sunday of Christmas weekend, a date I know as St. Stephen’s Day, I read a thoughtful editorial in the Washington Post by the conservative columnist George Will called “National conservatives and racial identitarians have a common enemy: Individualism”. While I didn’t agree entirely with his argument, and while in general Mr. Will and I only agree on a small number of things (in particular our mutual love of baseball) the main thesis of this column made good sense to me, that here in the United States individuality and the ability of the individual to express their self has fallen by the wayside in many circles in favor of a degree of collective identity on both sides of the political spectrum. The focus has fallen so much on what divides us that we’ve lost sight of how we are really so alike.

We are all Scrooges as long as we stay in our camps and refuse to venture out into the no man’s land between them. There are past wrongs that need to be delt with, crimes that have yet to be punished, I would be naïve to deny that. At the same time, we need something to bring us together, to break these circles of violence that have been carried out since the time immemorial, embodied in stories like the primordial Fall from Paradise described in the Abrahamic religions. At this point, it’s fair to say we’re in a time when revolutions and counterrevolutions born out of a spirit of vengeance are far more in vogue than any belief in a common humanity. Yet through the fog of war that we allow the dragons of our imagination to breathe out into our world, there are still those among us who send missions beyond Earth with hopes that knowledge will broaden our horizons and increase our knowledge of not only the Universe around us but of ourselves as well. This Second Age of Exploration offers us the chance to unite around a common purpose of bettering ourselves, of elevating humanity above that fog and into a new age in our history when we can achieve all those lofty ideals we continue to set ourselves from each generation to the next.