A Return – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

This week on the Wednesday Blog, some words about a trip just completed.

My world is one of open borders, the international scholarly republic of letters, and friends far and wide in this country and across the oceans. All of that shook to its core in 2020 when those borders closed, and friends grew apart with the pandemic we all experienced. I attempted to keep my life going in 2020, in those last few weeks before COVID-19 changed everything with a quick trip to Munich to see some university friends. Thereafter, for the last three years I kept to our own shores. A part of my wariness to travel far was a lingering worry that those borders could close again, that as I feared in 2020 so too even now there was a chance of getting stuck far from home.

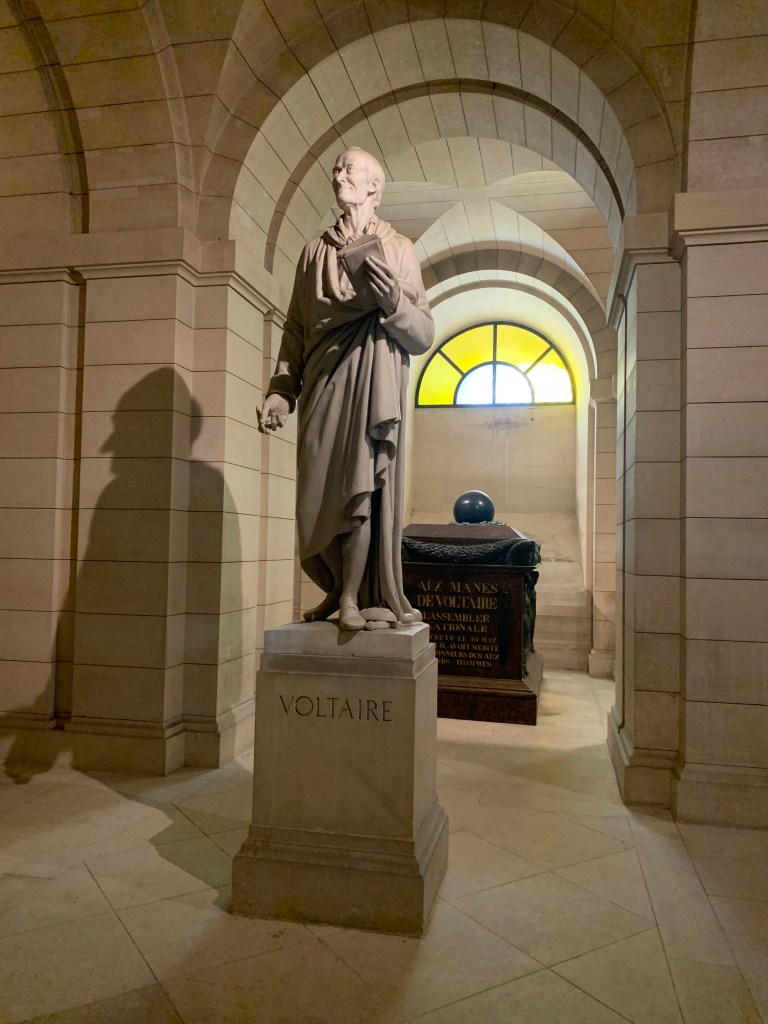

Over the last two weeks of October, I saw past that worry and made a joyous return to Europe, visiting Brussels, Paris, and London not just as an American tourist but as a historian hoping to realize dreams of walking the same streets as the humanists whom I study who lived at the end of the Renaissance 450 years ago. I arrived in Brussels on Sunday the 15th with an ease and lack of concern for doing or seeing everything I wanted to that betrayed a confidence that I’d return again in the future. And as I write this, I’m continuing with the research that will guide me back to Paris again.

In the stress and emotions of my daily life, I’ve learned to embrace the quiet moments, in which the sonorous radiance of the most joyous resurrections can be heard. That silence makes a return to places so close to my heart as wonderous as hearing Mahler’s great Resurrection Symphony in person. Why limit myself with worry when there’s an entire world out there to experience?

On this trip I found my favorite thing to do was to walk around and experience the city I was in. I did this most in Paris, when I arrived there around mid-day on Sunday, 15 October I ended up walking from Gare du Nord all the way to Notre-Dame, via Place de la République, the Marché Bastille, the Canal Saint-Martin, and Île Saint-Louis. The route took me about 6.4 km (3.7 miles) and lasted from around 11:30 until close to 14:30 when I descended into the Métro to make my way to the studio apartment I’d rented near the old Bastille. I loved returning to Paris in all its busyness, its sights, sounds, yes even smells. I was agog walking through the Marché Bastille and seeing whole fish lying on ice in the seafood stalls, there was even a shark with an apple in its mouth. If I lived in a place like this, I’d be sure to visit an open-air market every so often, if only for the experience of life that it offers. This entire walk, all 6.4 km of it, was done with a heavy backpack hoisted behind me as I didn’t think to look at Gare du Nord for the luggage lockers in the basement; use those, dear reader, if you have a long delay between arriving in a city and checking into your lodgings if the place where you’re staying doesn’t have a luggage room.

All in all, I walked 197 km (122 miles) on this trip across all 15 days. My feet are still sore, and my shoes need new insoles, yet I’d gladly do it again. Life on foot out in the open is much more personal than life behind the wheel of a car traveling at speeds at least 3 times my average walking pace. Whether in Paris, Brussels, or London, I took time to enjoy my surroundings, and to live as much in the moment as I could.

I found Brussels to be gloomier, the Belgian capital felt tired and like Paris well lived in. I was staying near the European Quarter in Ixelles, to the east of the city center and on my frequent walks back to my lodgings after dark I’d remark on how low the horizon felt walking those streets. Unlike many other cities I’ve visited, the high apartment buildings seemed to block off the lowest reaches of the night sky and the overhead glow of the city lights which illuminated the streets shaded my eyes from seeing up towards the heavens. It was like some of the stories I remember seeing as a child, stories told on the screen which were set in this sort of world where the mysteries of the skies above are darkened by a radiant yet feeble attempt at letting there be new light which makes the world all seem smaller and more confined. Far from utopian, for this light tells me I am somewhere, it still left me wanting for more and grander visions of the Cosmos far from those streets.

Returning to London felt as though I was returning to a long lost home. I strolled down the platform at St Pancras when I arrived beaming a broad smile after days unsure what I’d find or think arriving in that city. I soon found my way around the capital with ease, much of what I’d known during my life there in the middle of the last decade was as it had been. I returned to most of my old favorite places––the museums, the streets & squares of Fitzrovia, Bloomsbury, and Mayfair––and to the place where I once lived on Minories just beyond the old city walls. On my last evening there I sat for a while in the garden behind my old flat, the one my window looked out onto, and thought about all that had happened since last I was there.

I returned to Europe a different person from who I was when last I crossed the Atlantic. The Pandemic and my years of doctoral study shaped my youthful optimism just as it sculpted my ever-receding hairline. I returned to Europe less worried about losing something I had in the present and more appreciative of that moment I was in, of the places I was walking, the people I was seeing, whether for the first time ever or for the first time in years, and still hopeful that one day again I will return to these places. I do hope it’ll be sooner, whether just to visit or to live remains to be seen.

As much as this trip felt like a return to a life I once knew well, it also felt different from my past when I lived across the water because I’m a different person now. If any experience in my life could feel like a “return to normalcy” to quote Warren G. Harding’s campaign slogan of 1920 it would’ve been this; yet there is no real returning to an old normal, for we are never the same. I felt this when I returned to Kansas City after living in Europe; I was gone for just under a year, yet it felt like I had missed so much. Some things remain yet eventually all things must change. For the first time in my life, I’m happy to accept that, and to embrace that change as a good friend.