A Keepsake – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

This week, I take you along on an investigation I undertook recently into a family heirloom from World War II.

Of all the bad things that came out of the flood which struck my family home two weeks ago, there were several intriguing finds in old boxes, chests, and crates that hadn’t been opened in several years. Two days after the flood, I finally got around to opening my Donnelly great-grandparents’ blanket chest, which held most of the surviving physical records of their lives. It was deeply dolorous to lose these pieces of their memory, and to know that while we will have photographs of these artifacts going forward, most of the artifacts themselves were ruined by the sewage that flooded into our basement.

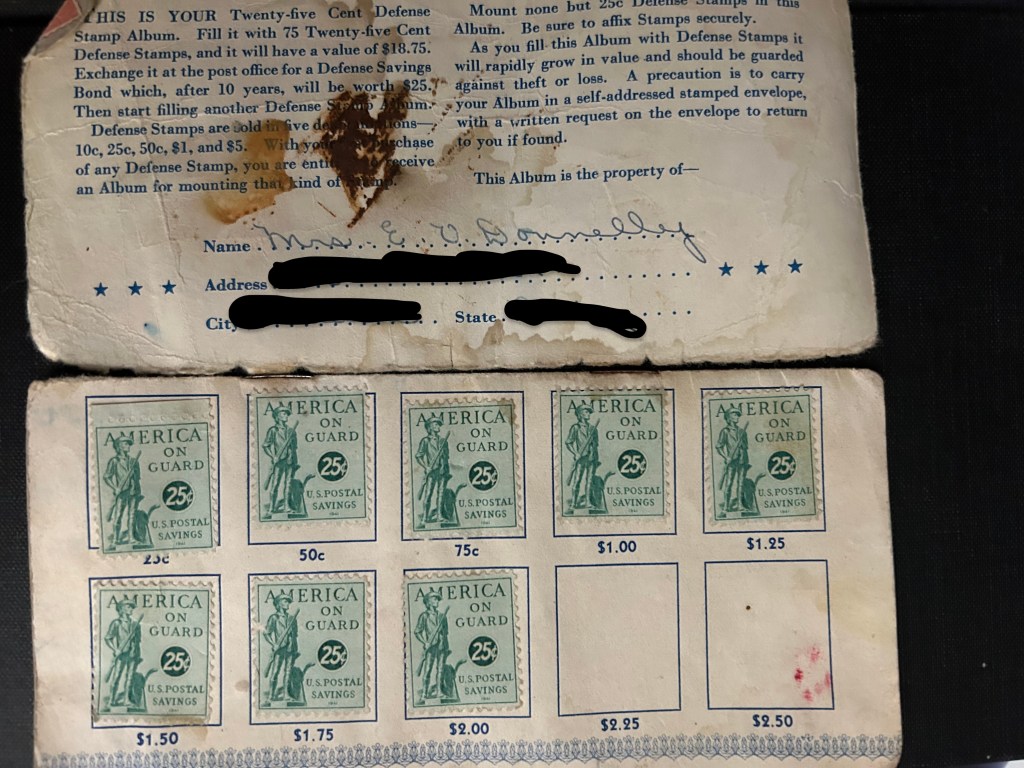

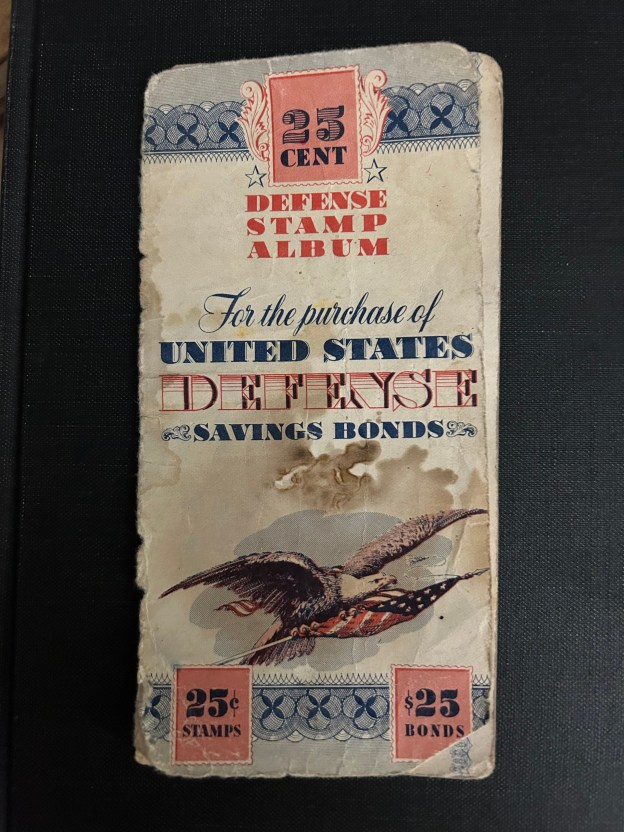

One of these artifacts that caught my eye was an album of United States Defense Savings Bond Stamps dating from likely 1942. These were printed for civilians to purchase and collect 25¢ stamps which they could then turn in after the war at their local post office for savings bonds which could then accrue value over time. My great-grandmother Ruth Donnelly bought this stamp album when she was living in Glendale, Arizona where my great-grandfather was stationed when the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked Pearl Harbor. He was a cavalryman, just a few years out of Rockhurst College, my alma mater as well. When the war began, the U.S. Army decided to not send the cavalry overseas with their horses, seeing how poorly the Polish Cavalry fared against the German Wehrmacht in 1939, and being too tall to serve in the tank corps he was reassigned to the infantry.

I’ve often wondered what it was like for my Donnelly great-grandparents when he was away in the Army during both World War II and Korea. When I used to volunteer at the Kansas City Irish Center at its old location in the lower level of Union Station, I’d often find myself in that grand old building later in the evening and would walk up into the great hall and think about them there when he deployed. That was during my high school years when the Afghanistan and Iraq Wars were at their height and reports & stories of deployments, reunions, and the planes returning fallen servicemen and women were a frequent fixture on NPR and on the morning & evening news.

Of all the artifacts that we recovered then, I decided it would be good to see if I could turn in the stamps my great-grandmother, or G.G. as my cousins & I called her, for anything today. Surely, over 80 years they would have gained some monetary value. My first stop was to my local bank branch, where I took them to the counter and with a smile explained my unusual visit. The tellers who were working that afternoon gathered at the window to look at the album, having never seen its kind before. One read the fine print and suggested that I needed to go to the local post office first and see if the Postal Service still would collect these stamp albums in exchange for savings bonds. After all, if the coins and bills of the U.S. Dollar don’t expire, then why should this stamp album that could be exchanged for savings bonds expire?[1]

With this in mind, I drove from my bank branch to the nearest post office and joined the queue. The postal clerk there was just as surprised to see this album as the bank tellers were. She had never seen an album like this before and suggested I should go to the Kansas City Main Post Office at Union Station where there might be some veteran postal workers who would have possibly exchanged these albums for savings bonds near the turn of the millennium. That made sense to me, and following the trail further I drove downtown to Union Station. At the moment there is a major exhibition from the Walt Disney Company honoring the studio’s centenary, so Disney music is echoing from the loudspeakers all around the building where once they would have announced arriving and departing trains. The Main Post Office moved about 20 years ago across Pershing Road to its current place in Union Station after the old post office building was converted into the Kansas City IRS regional offices.

My last visit to the Main Post Office for more than just buying stamps or dropping off letters was in the hot summer of 2012 when I got my passport photo taken there. It was at the same time that the Opening Ceremonies of the Summer Olympics were underway in London, though they weren’t televised live in the U.S., instead being shown in primetime later on NBC. I always laugh when I look at that passport photo: I wore a suit and tie and between the over-exposure of the image and the buckets of sweat on my face I looked quite silly.

This visit to the Main Post Office was greeted by the same voice of surprise from the clerk as the three other people who I’d taken this album to so far. I explained what I knew about it, that it was likely 80 to 82 years old, and that I wanted to see if the stamps inside could be exchanged for savings bonds still. I opened it to show the clerk that my G.G. had only collected $2 worth of stamps, so it wasn’t a full album. He wasn’t sure what was the best answer and retreated to the offices behind the counter, returning a few minutes later with the name, address, and phone number of a stamp auction house in town that I could consult for a better answer.In short, I could not exchange these stamps for savings bonds anymore. The people who would know how to do that were long since retired from the Postal Service. After three stops, I was ready to hear this, and returned home, where I called the auction house and spoke with its owner. He explained that these stamps have some collectable value, but nothing of any real significance. At the end of the day, while the capitalist in me was disappointed, I was overall pleased with the result of this research. I called my grandmother to tell her the news, saying that this stamp album would make a nice keepsake for future generations to find again, and if this Wednesday Blog is also lost, to research again. Who knows, maybe in another century it might end up on Antiques Roadshow.[2]

[1] United States Federal Reserve FAQs, accessed 27 August 2024. https://www.federalreserve.gov/faqs/currency_12768.htm#:~:text=No%2C%20you%20do%20not%20have,of%20when%20it%20was%20issued.

[2] I hope the set decoration of that show still keeps that eternal 1980s & 90s feel in the 2120s.