On Boston – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

This week, some comments about my trip to Boston last month and reflections on that resilient city.

I’ve been to Boston several times now, once in my childhood on a family vacation and twice for work. It’s the furthest of the east coast cities from Kansas City, and in some ways it’s rather hard to get to from here. Yet, the influence of Boston in particular, of Massachusetts in general, and of New England overall is quite pronounced here in the Midwest. When I was in the first semester of my History MA program at the University of Missouri-Kansas City one of my favorite books from the American History Colloquium I took discussed the patterns of westward settlement from the old eastern states during the Early Republic. From this, I learned that the reason why New York and New England felt more familiar to me was in part because it was New Yorkers and New Englanders who settled the parts of Northern Illinois that became the metropolis of my birth, Chicago, as well as many of the original towns in Kansas. One aspect of the Bleeding Kansas conflict of the 1850s, an overture of sorts to the American Civil War of the 1860s, was that Missourians with southern roots found their culture clashed with Kansans who were recently arrived pioneers from the North.

I remember really enjoying my childhood visit to Boston for a great many reasons. We did most all of the touristy things in that city, though I realized later on that we hadn’t visited some of the finer art museums in town like the Museum of Fine Arts or the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. That thought rested in the back of my mind for about twenty years until I returned to Boston as a doctoral candidate in October 2021 on a mission to see how the first French published translation of the Odyssey translated the Greek word ἄγριοι, which Robert Fagles translated into English as “hard men, savages.”[1] The French translator in question, the sixteenth-century humanist Jacques Pelletier du Mans (1517–1582) rendered ἄγριοι as “rude and uncivilized men.”[2] The copy I accessed of this book is housed in Harvard’s Houghton Library, and so I made a trip out of a word-search and found so much to admire about Boston and the surrounding suburbs in the few days I was there.

For one, the vintage of that region as one of the great nests of Anglo-American culture has always felt familiar to me, as that is in many respects the roots of my own culture albeit with many more layers of immigrant influence stacked atop it that form my idea of America. When I drove to Boston from Binghamton in October 2021 amid the incandescence of the Fall leaves I kept remarking on the smaller size of so many a Massachusetts village and town each of which was founded in the eighteenth or even seventeenth century. Where towns in Colorado celebrate their altitude and towns across America commend their population, in that Commonwealth each town’s age is celebrated as a mark of pride. My appreciation for this was less driven by an amazement at seeing such old places, I’ve been to many an old city, town, and village in Europe. I’ve even stayed in buildings that were erected 500 years ago like the place I chose in Besançon. What struck me most here was that these old houses were present here in America, in the United States. After all, my homeland in the Midwest has few colonial buildings left for us to mark with signs or commemorate as local landmarks. The French presence was far stronger along the Mississippi south of the Missouri River than in Chicago or Kansas City. Both of my home cities trace their founding to dates after American independence in 1776 and the birth of the republic in 1787.

Where I have seen this fortitude in a city in the middle third of the country is in San Antonio, an old Spanish settlement founded in 1718 at a time when it fit into a world among the vast global empire of the Spanish crown, connected more to the Canary Islands in settler population than to even more distant England or her colonists’ descendants who moved southwest into Texas a century later leading to that region’s independence and later annexation by the United States. The English-inspired east then annexed the Spanish-inspired southwest in the same manner that thirty years earlier it’d purchased the French-inspired Midwest. In this way, I’ve found New England more reminiscent of England itself than of so many other parts of the United States. It shares more of a common culture and history with England, and in many respects remains the child that chose to go its own way when it could and embrace republicanism in contrast to continued English royalism. I’m sure there’s something I could say here about Cromwell, but I’ll leave that particular figure of English colonial ambitions in Ireland for a less sentimental blog post.

This time, I traveled to Boston to attend the 2025 meeting of the Renaissance Society of America at the Marriott Copley Place in the Back Bay neighborhood to the south of downtown. What’s funny to me is that I don’t remember going anywhere near Copley Square or Back Bay on any of my previous trips to Boston, though I did pass underneath both the square and neighborhood on the Green Line trolley in October 2021 when after completing that wordsearch at Harvard I decided to take the afternoon to visit the Museum of Fine Arts. I remember being impressed by the collection I saw, though I got overwhelmed in some of the galleries and feeling a bit tired after a long day I returned to my friends’ house in the suburbs. On this most recent trip I elected to visit the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum instead of its neighbor, the Museum of Fine Arts, having heard so much about Ms. Gardner and that museum’s infamous midnight robbery in 1990. I was happy to see how lovely a museum it was, from the garden at the base of its courtyard to the spiraling series of galleries largely unchanged since the museum was built at the turn of the last century. In the museum there is a portrait of Ms. Gardner full of life and joy which was so personal that her husband asked it to remain away from public view until after he died, resulting in the room in which it lives being closed to the public until after his death in 1898. Gardner was friends with many of the American artists of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries who I greatly admire, including John Singer Sargent and James McNeill Whistler whose paintings in the Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery of Art in Washington contribute to that gallery being one of my favorites of the Smithsonian Museums.

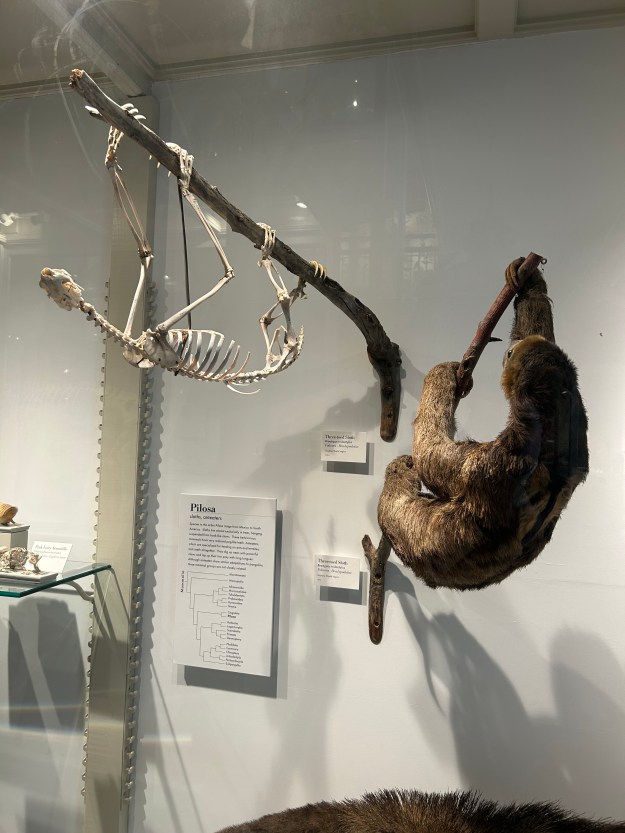

To reach the Gardner Museum meant taking the trolley through the campus of Northeastern University along Huntington Avenue. Over the few days I was in Boston I also visited two other local universities, Harvard to visit their Museum of Natural History and to attend a concert of medieval liturgical music at St. Paul’s in Harvard Square, and UMass Boston to visit the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library right at the end of my trip. What struck me most about this trip, and what filled me with a greater sense of relief and, yes, joy was seeing how many students were out and about in that city. It felt as though the storm clouds that hover over all of us could be held back if even as a reflection on water by a sense of camaraderie that proved elusive only a few days later when the first wave of student deportations swept up a fellow doctoral candidate at Tufts University in that same city. Still, in the days I spent around the students of Boston and among my fellow Renaissance scholars I was struck by how profound that sense of camaraderie was that in spite of the troubles we see around us we are going to chart a course through the ice and out into calmer, open waters again.

Boston has seen a great many generations live on its headlands and about its bays in these last 395 years since its founding as the capital of the old Massachusetts Bay Colony. In the weeks since, with that trip still fresh in my memory I was reminded of the illustrious revolutionary history of that city and of Massachusetts and the resilience of its people and their peculiar traditions of democracy which have influenced the spread of representative government across this continent through the ideals of the United States and our Constitution. I’m sure it will weather this storm as it has so many before it. Knowing too my own profession, my desire to find a professorship or museum job first and foremost, I suspect I may find my way back to Boston again. After all, not only are there many universities there with healthy endowments, however rare those may become in the years and decades to come, that city remains a vibrant city, a living city, a city that hasn’t carved itself out for sprawl in the way that so many others have. I was struck by how profound that sense of connection and community was there.

Nice place.

[1] Homer, Odyssey 1.230, trans. Robert Fagles, (London: Penguin, 1996), 84.

[2] Homer, Premier et Second Livre de l’Odissée d’Homère, trans. Jacques Pelletier du Mans, (Paris: Claude Gautier, 1571), 10v.