When I returned home to Kansas City about a month ago, I saw an email from the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art that the Tivoli Cinema, which since 2020 has been housed in the Nelson’s auditorium, would be holding two showings of Fritz Lang’s 1927 silent masterpiece Metropolis. I jumped at the opportunity and immediately bought a ticket for the opportunity to watch this film on a big screen with an audience around me. So, this past Sunday afternoon I showed up for the matinee screening and was even more dazzled by the experience than I’d expected.

I had seen Metropolis once before when it was on Netflix about a decade ago. I remember feeling a bit wary of the film and its story when I first watched it that time. Now I know that watching a movie as monumental as this one on a screen as small as my laptop does a disservice to the whole experience. Metropolis was made to be seen on the big screen with a live orchestra, or at least a live organist, adding a whole extra dimension of music to this already vivid story. In the case of this weekend’s showings, Metropolis was accompanied by a 2010 recording of the original Gottfried Huppertz score performed by Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra conducted by Frank Strobel. I’ve since played that recording again on iTunes while grading essays this week and have felt just as profoundly moved by it as I was in the theatre on Sunday.

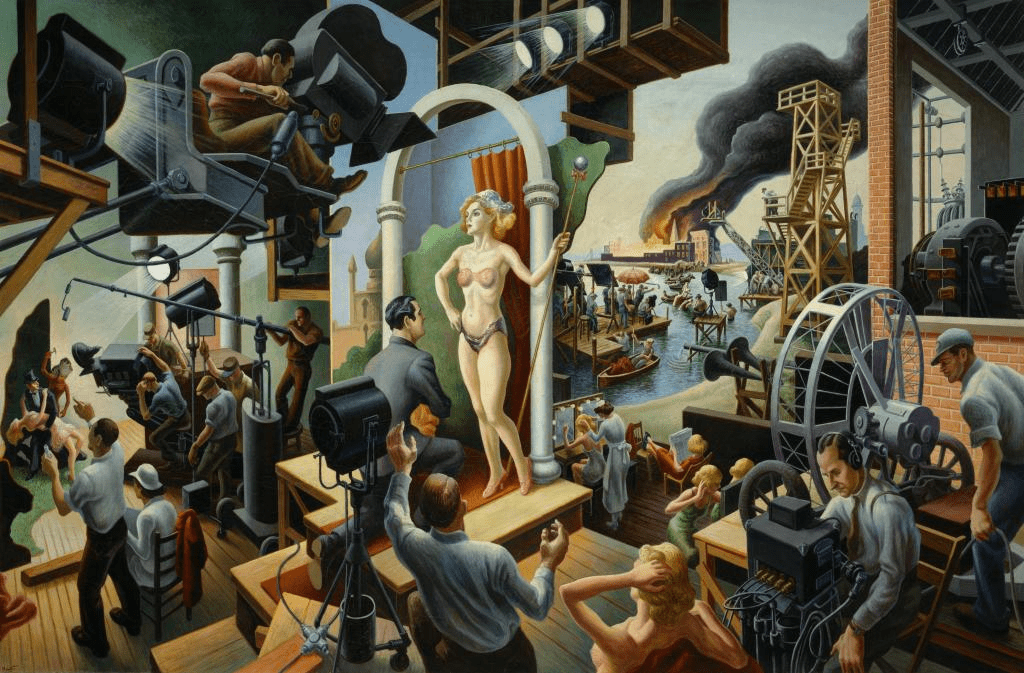

It occurred to me while listening to that album again this week that as much as this score is a film score, listening to it on its own it feels far more like ballet music. In the past I’ve written about how I feel that ballet and silent film share similar characteristics born out of their mutual need for wordless expression to tell their stories. As I listened to Huppertz’s score without seeing the images in front of me I found myself thinking back to each particular scene in Metropolis as I’d seen them the day before. Yet in the moment as I sat in the third row of the Atkins Auditorium watching this spectacle unfold before me, I felt that Metropolis was more operatic than balletic in its very character. These were actors performing at a time when the quantity of film influences were far fewer on their lives thanks to the relatively recent invention of motion pictures, film at that point was only about 40 years old.

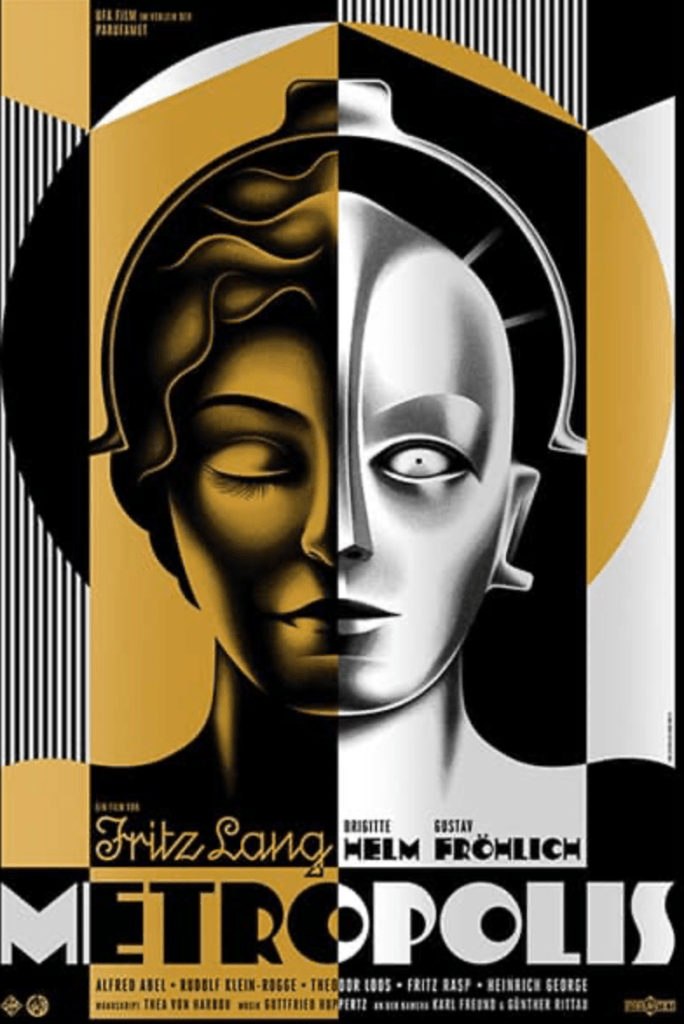

In Metropolis I saw echoes of Wagner and Strauss as well as hints of the future, all the films and television shows that would follow it. There is a scene near the beginning of the film’s first act, the 45-minute prelude, where a shift change of the underground workers occurs that seemed strikingly similar to several scenes from the new Star Wars: Andor series released on Disney+ this Fall. Don’t worry, no spoilers here. There are many elements of Metropolis that certainly have been influential, look no further than the Machine-Man, the poster child of Metropolis that wreaks havoc on the city and nearly destroys it and all who live within it. There perhaps we see the ancestor of Doctor Who‘s cybermen, Star Trek‘s Borg, or Alicia Vikander’s character in Ex Machina.

In the last few days, I read in Variety that there’s a TV series remake of Metropolis in the works for Apple TV+. While I’m normally hesitant about remakes of classic films or shows, the new Star Trek: Strange New Worlds which sees the adventures of the original 23rd century USS Enterprise before it was captained by James T. Kirk, has made the idea more amenable to me, though that’s likely because Strange New Worlds does the whole reboot idea perfectly. I’m most curious to see how Apple TV+’s new Metropolis will depict the city of tomorrow. In 1927 Fritz Lang’s original film used the great art deco skyscrapers of New York built of brick and steel as his model. Will this new series seek to depict the sort of futuristic architecture that I’ve collected on my architecture Pintrest board, filled with gentle curves, evocative colors, and dramatic lines? That remains to be seen.

Metropolis was a gripping film to see, and while long, with some aspects perhaps a bit old fashioned to our tastes, notably the over-the-top heart-gripping that happens throughout that made the crowd around me laugh from time to time, it still has my attention caught even now a few days later. Silent films speak to us in a way that their talking counterparts created after 1927 simply don’t. They tell stories in different ways, adjusting their style to fit the technical limitations of their time. I’ve always been drawn to silent films for this reason, and perhaps I’m drawn to ballet for much the same reason. After all, Chaplin was as much a dancer as he was a slapstick comic. Metropolis is a testament to the time and place in which it was made, Weimar Germany in the 1920s. In Joh Fredersen, the master of Metropolis I see Henry Ford, both in his character and in his physical appearance. I see fears about extremism on all fronts, and a call for unity and dialogue in the face of anger. I wonder what the new Metropolis will be like?