Homo Sapiens – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

On Monday last week, I sat down to watch the 2007 film The Man from Earth for the second time. You may remember hearing or even reading my reflections provoked by that film. I said I’d probably watch the sequel, The Man from Earth: Holocene soon, and well I did just that. Compared to the original, Holocene lacks some of the powerful dialogue, and the gripping storytelling. The Man from Earth felt like it was a story being told in real time, while Holocene, its sequel, seemed more like a TV pilot that was turned into a feature. Both films feature some wonderful actors that I recognize from the many Star Trek series I’ve seen in the last few years, notably John Billingsley and Richard Riehle in the first film, and the great Michael Dorn himself makes a wonderful appearance in the second film.

If I were to draw any deep arguments out of the second film, Holocene, it would be something to do with how we identify ourselves. We humans call ourselves Homo sapiens, a scientific designation that we’ve given to ourselves to distinguish us from our hominid cousins including the Neanderthals. Homo is Latin for human; it is the genus which represents all hominids as a subset of primates. Sapiens on the other hand is more interesting. It is a Latin participle based on the 3rd conjugation verb sapiō, sapere which is used to mean many things from “to taste,” “to have flavor,” to the more innate concept of being able to sense or discern things, all of which is necessary for knowledge. Homo sapiens then means we distinguish ourselves from our hominid cousins by our abilities to understand ideas. Now there’s evidence today that other early humans could think and create in ways that are similar to us, evidence for example that Neanderthals created art of some sort in ancient Europe, so in many ways the fact we designate we humans as Homo sapiens is as much a way of patting ourselves on the back as anything else.

This brings me back to The Man from Earth: Holocene. It’s a film that introduces the core conflict when a group of inquisitive undergrads start to wonder about their professor who they soon realize is the same 14,000-year-old man from the first film. Only now he’s begun to age in slow but noticeable ways. This film made me question the idea that we are Homo sapiens for the personifications of humanity in this film, the four students seeking the truth about their professor, make a series of terrible decisions that prove as book smart as they might be they are clueless to so many other factors of life. Homo sapiens indeed.

In my own research I study the introduction of Brazilian flora and fauna into European natural history through the writings of several French explorers dating to the 1550s through the 1580s. And while I came into my research thinking I would have some fun writing about sloths and parrots and dyewood trees, I have found that the story I’m trying to tell is as much a warning to our present and our future as it is anything mundane about Renaissance natural history. There is a theory, an idea that is introduced late in The Man from Earth: Holocene called the Anthropocene, a concept that is widely discussed today which argues that human interventions and influence upon nature have become so great that we have shifted the course of Earth’s natural development from the Holocene, the current geological epoch defined by our planet’s warming by the Sun over the past 11,650 years, making for the perfect conditions for the development of life as we know it today into a new geological epoch where we humans, the Anthropoi in Greek, are now the prime movers of Earth’s natural course. In the film this becomes an understated note of caution, yet in my own research I find the Anthropocene to be a fundamental piece of the story of the European exploration, conquest, and colonization of the Americas largely ignored until recently.

We call ourselves discerning, we call ourselves wise, and yet we allow our own demands on nature to outstrip what nature can provide. It’s a curious balance we need to maintain, one which I am just as guilty of destabilizing as anyone else. It’s curious to me that we call ourselves wise when we think of all we have done with our home. We are one of maybe only a handful of species (leaving room here for other hominids at least) that has created beautiful art and weapons of mass destruction all with the same innate tool: our brains. We have just as much an ability to love as to fear, and in a given day I think it’s safe to say we act on those emotions without often really realizing it.

Through it all we’ve survived and thrived on this planet of ours. There are 7.9 billion of us today, and while our population growth is a marvel of our ingenuity and ability to adapt to everything that this planet has had to offer so far, our own exponential growth may be the thing that drives the planet to the point of no longer being able to care for us the way we have been. If we don’t eat, we starve, yet if we eat too much we will run out of food and then starve. As the Man from Earth himself said in the first film, it’s the species that live in balance with nature that survive.

I argue in my dissertation that the Anthropocene really began when two different gene pools of life, one Afro-Eurasian the other American intersected in a large scale for the first time in thousands of years following Columbus’s accidental stumbling on land and people on this side of the Atlantic in 1492. That was the moment when human endeavors began to triumph over natural barriers, when a new global world was first conceived out of the collective products of a series of old worlds on every inhabited continent. It’s fair to call ourselves sapiens, discerning and wise, for the fact that it was humans who bridged that gap through innovation and technology. Yet it’s also fair to say that it was humans too whose innovation and technology created the great climate crisis we find ourselves in now. While the pessimists among us would end the story there, in a way that is in vogue to do these days, I want to continue the story, to contribute a verse to the poetry of life and say to you here and now today that it will be our innovation and technology, our discerning and wise nature that will figure out a way out of this crisis and that will lead us to adapt again to a new life in this new world we’ve created in our own image.

The Man from Earth speaks to me of the potential of humanity and of how at the end of the day we’re still just telling each other the same sorts of stories around a campfire. Like our ancient ancestors before us we see what we know and imagine what could be out there beyond the light of our knowledge. Unlike our ancestors we today are comfortable in a world we’ve created for ourselves, or at least some among us are comfortable in that world. We don’t need to innovate quite so greatly as past generations; we can let our minds become lazy and unimaginative. Like the big wigs from every time just before a storm we can be content and let the tides overcome us, but some among us will be hit more fiercely by those tides than others, and they’ll be the ones to stand up and say we can do better for ourselves. We will always stumble and fall, like those four characters from The Man from Earth: Holocene but we will always find a way of getting back up.

At the end of the day, we’ve created this new world where we are at its center, the keystone species around which all others exist in a new balance. I personally find that balance more precarious than I’d like, and personally I’d rather not be the one holding the entire balance of nature up like some modern Atlas. Yet over generations of decisions for good or ill this is what we’ve decided to do, and who we’ve decided to become. All we can do now is live up to the task and make the burden less strenuous for our descendants.

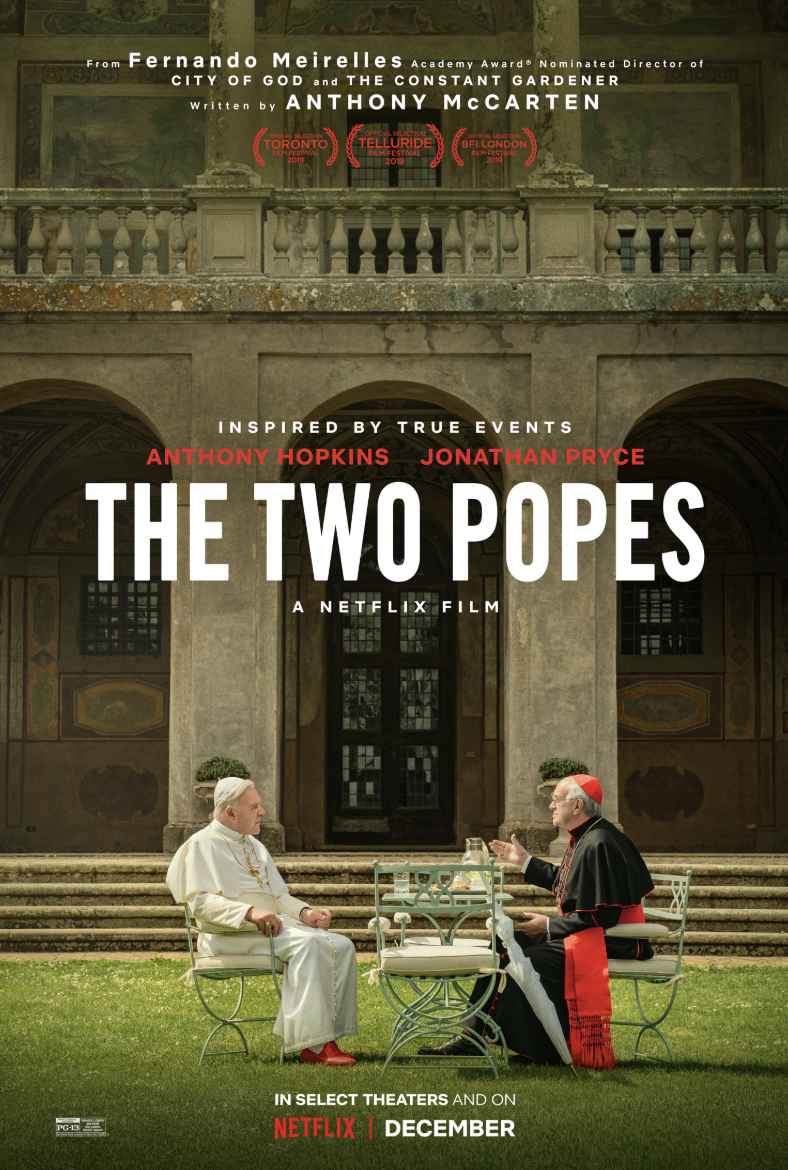

Netflix’s new two-hour film The Two Popes starring Jonathan Pryce as Pope Francis and Sir Anthony Hopkins as Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI is theatre, pure and simple. It falls into one of the most classic sorts of plays, a dialogue between two men with similar positions yet very different experiences. While not all the conversations that make up The Two Popes may have happened, according to an article in

Netflix’s new two-hour film The Two Popes starring Jonathan Pryce as Pope Francis and Sir Anthony Hopkins as Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI is theatre, pure and simple. It falls into one of the most classic sorts of plays, a dialogue between two men with similar positions yet very different experiences. While not all the conversations that make up The Two Popes may have happened, according to an article in