Close Encounters of the Three-Toed Kind – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

You’ve heard me talk at length about a fair number of topics on this podcast, and those of you who have been reading my blog now for the 60 straight weeks that I’ve been writing it will perhaps know parts of me a bit better than some. This week I want to talk to you about something that’s personal yet also professional, it’s the project I’m staking my career on at this early stage––my dissertation. The big document I’m writing now is called “Trees, Sloths, and Birds: Brazil in Sixteenth Century Natural History.” It tells the story of how those three groups––the trees, sloths, and birds––were introduced to European natural history by a French cosmographer named André Thevet (1516–1590) in his 1557 book The Singularites of France Antarctique. It’s been a fun project to write so far after years of research and nearly a year of fighting to get it approved. At the moment, I have the first two chapters written and the next two, the sloth chapters, in the works.

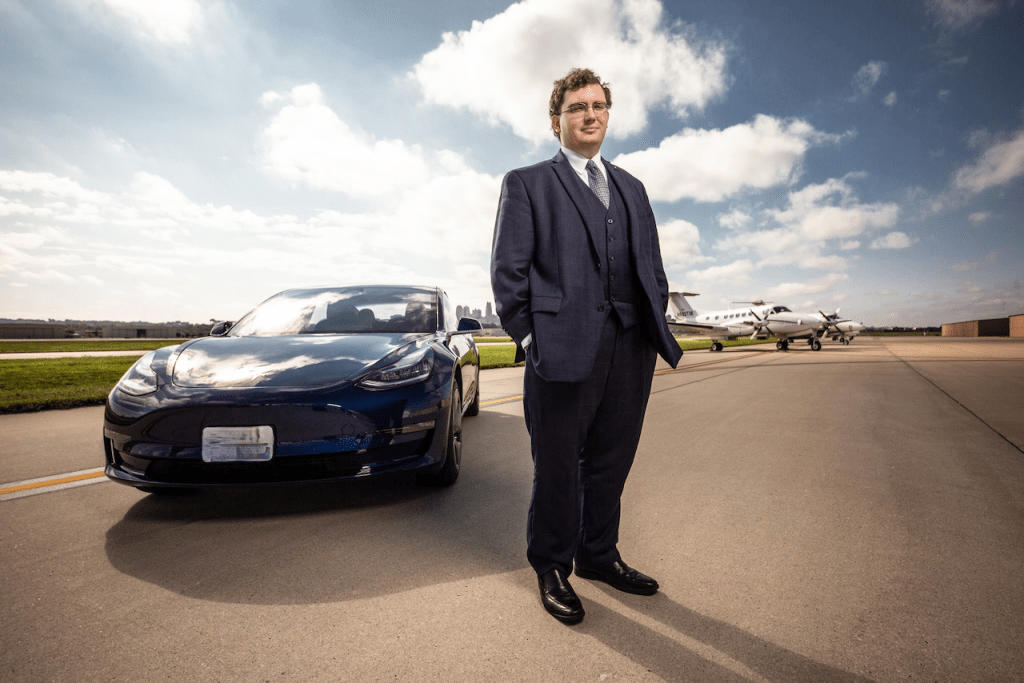

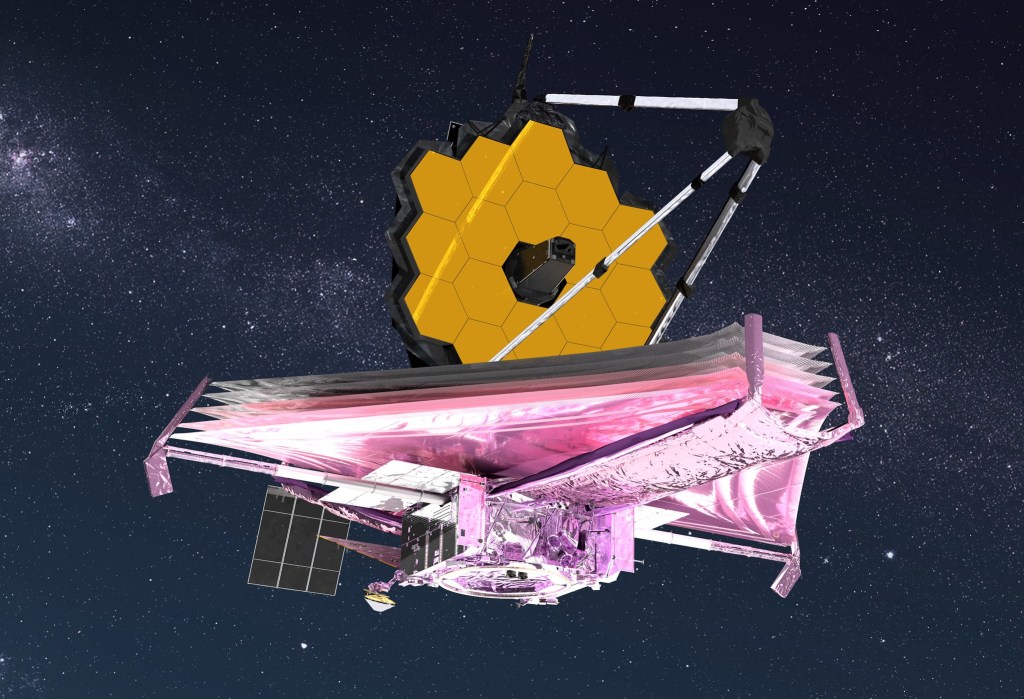

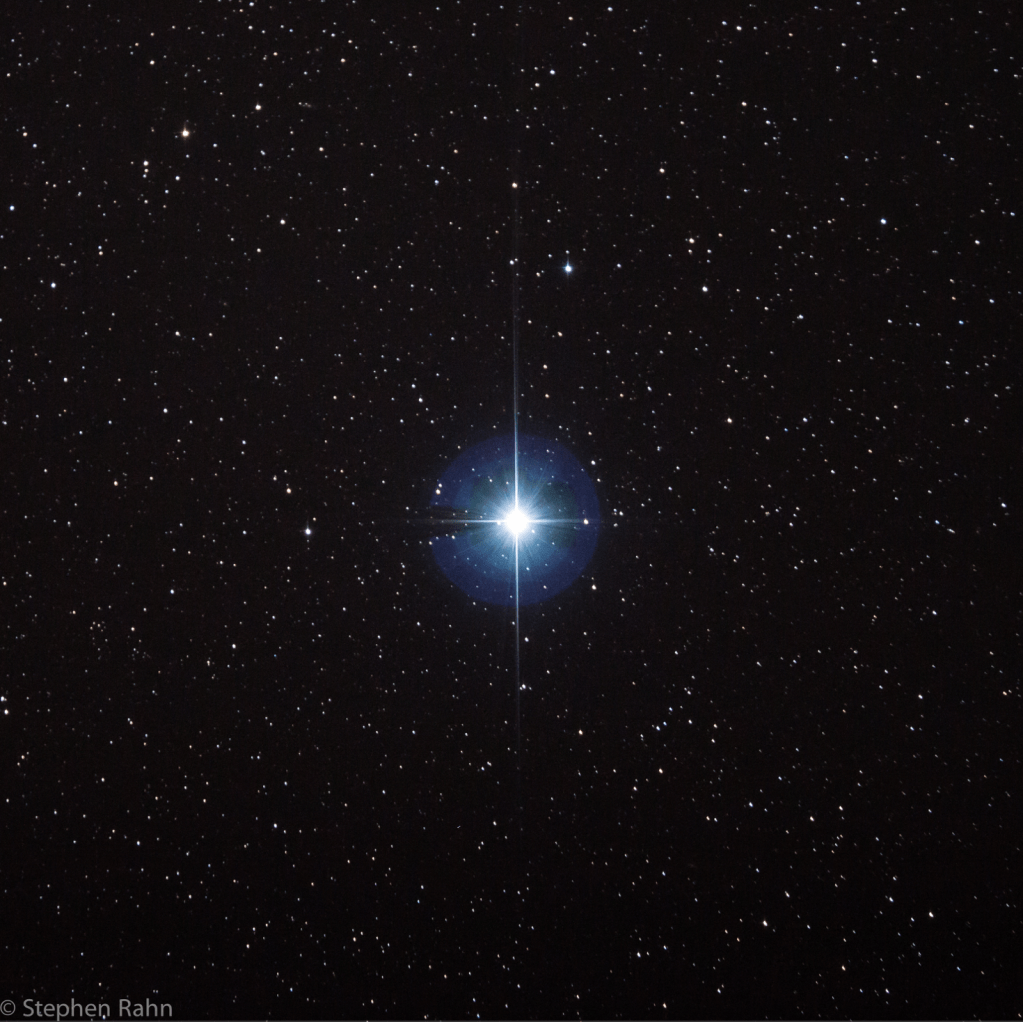

So, naturally this seemed like a good time to stand up in front of a crowd and announce my intent to study the history of the natural history of sloths to all the world. This Friday, 29 April, at 8 pm Eastern I’ll be giving a public talk about my sloth research called “Close Encounters of the Three-Toed Kind: How Unknown Life was Named in the First Age of Exploration”. I’ve got to admit, I’m going out on a big limb here, and not lazily or slowly either. On Friday evening I’ll be introducing not only my research about the three-toed sloth’s role in cementing the strangeness of American zoology in European eyes but arguing for the recognition of what we today call the Age of Exploration, the period that began when Columbus stumbled on the Bahamas in 1492, as in fact the First Age of Exploration. The reason for this is straightforward: 61 years ago, humanity entered a Second Age of Exploration at the moment when the first human left the Earth’s atmosphere and entered Space beyond. Yuri Gagarin’s monumental first spaceflight is a moment that ought to be marked as the beginning of a new age in the human story, one where we began to move, however slowly, towards venturing out of our home and into our planetary neighborhood at the very least, our stellar neighborhood in the long run.

I don’t think it’s anachronistic to say the way Thevet and his contemporaries understood the sloth in 1555 and 1556 is similar to how we might well understand life that’s new to us that our explorers in the coming years might well encounter on other worlds. In Thevet’s time the Americas, these continents, were seen as an alien world by the Europeans, it was as foreign, as strange as they could imagine. In their efforts to make sense of what they saw and who they encountered in those first generations of contact the European explorers often either gave names familiar to them to that American life they encountered, as with the sloth, or they adopted local indigenous names for the life of these continents, as in the case of many of the local peoples they met. All of the states in my home region, the Midwest, bear indigenous-derived names, largely drawn from the names of local peoples who the French encountered and traded with during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

The main theme of my talk will be about the meaning of names, their importance and intrinsic value to the named and the one doing the naming. In the first fifty years of its inclusion into European natural history the three-toed sloth went by several names. Thevet first recorded it in 1557 as the haüt, a Middle French phonetic spelling of the Tupinambá name for the creature, itself derived from the sloth’s cry which Thevet described as like “the mournful sigh of a small child.” Haüt also appeared in Conrad Gessner’s entry for the sloth in his 1567 Thierbuch, a German translation of his History of Animals, first published in Latin before Thevet’s visit to Brazil in the 1550s. Yet Gessner himself gave the sloth a more scientific name, Arctopithecus, meaning “bear-like ape” out of an effort to identify it by its physique, or how at least Thevet described its physique in his writing and a woodcut of the animal in his Singularites. Another French writer, Jean de Léry (1536–1616) who visited Brazil after Thevet left in 1556 and 1557 called the animal a Hay, with a closer phonetic spelling to the modern Aí. Yet it was the Portuguese who first called this animal a sloth, namely the Spanish Jesuit missionary St. José de Anchieta (1534–1597), whose letters to his Jesuit superiors describe the animal as a preguiça in Portuguese, a sloth in English.

Another epithet Thevet gave to the sloth in his 1575 book the Universal Cosmography referred to it as “the animal that lives only on air” because during the 26 days that he kept one in captivity he never saw it eat or drink. Therefore, in Thevet’s logic, the sloth must only nourish itself on the air surrounding it. How Thevet didn’t realize the animal was probably terrified from being brought indoors, and likely was starving and dry for thirst baffles me. Still, the idea that Thevet believed he had found an animal in this alien world of America that “lives only on air” meant that the sky was truly the limit for the possibilities of American life. Thevet’s own Twilight Zone contributed to the groundwork for the notion of alien worlds that persisted in speculation and fiction into the present day, beyond the bounds of his own Age of Exploration, which I might argue ended with the competing Amundsen and Scott expeditions to the South Pole in 1911, or perhaps with the gradual end of the old colonial empires over the last century. So, if you’re in the Southern Tier of New York this Friday and want to hear me talk about sloths come up to the Kopernik Observatory and Science Center in Vestal, New York. The talk begins at 8 pm on Friday, and if the skies are clear, as hopefully they will be, we should have some wonderful opportunities for some stargazing after I wrap up my show. And for those of you who are listening from afar you can watch me take the stage live on YouTube. The link is in the show notes.