Click the Instagram logo above to follow my updates of this trip as they happen.

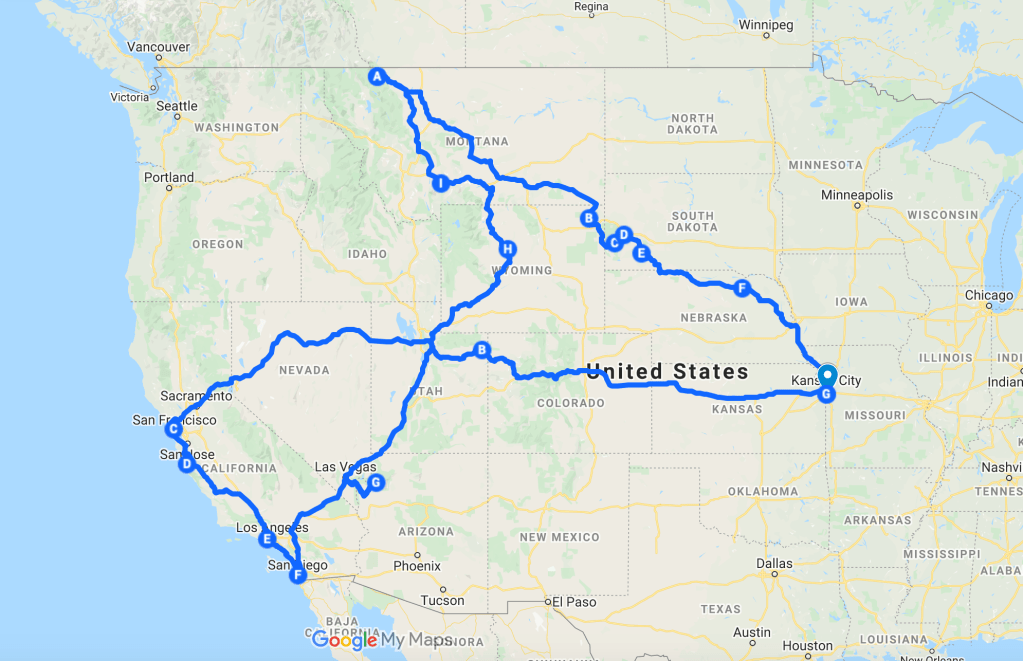

For many years now I’ve thought about the idea of taking a big road trip across the Western United States. For a while my idea was to drive from Kansas City up to Portland, Seattle, and Vancouver, before my focus shifted southward toward trying to go to the Monterey Bay Aquarium in central California. Last spring and early summer, in the midst of the first stages of the COVID lockdown, I began to plan what would be the trip of a lifetime.

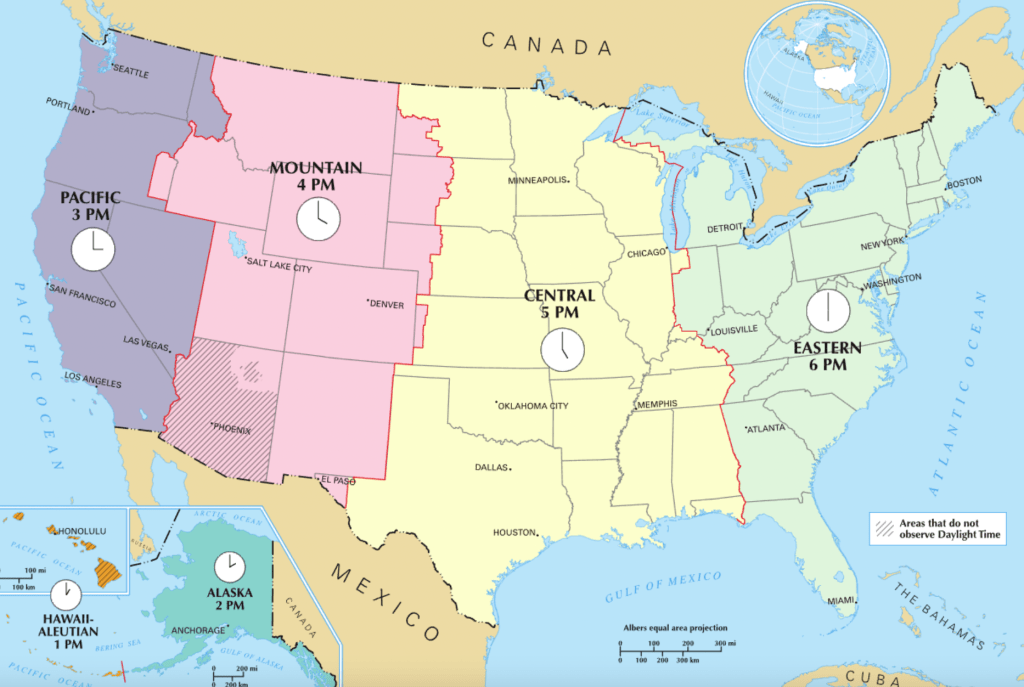

It was to be six weeks driving across the western states, beginning in Kansas City, going through Denver, then onto Salt Lake City, before crossing Nevada and driving down from the Sierras into California before finally making my triumphant arrival on the Pacific coast at the Golden Gate Bridge. From there, I was going to drive south along the Pacific Coast Highway to San Diego, before turning northeast on I-15 and heading out of California towards Las Vegas, with a detour to see the Grand Canyon, and a quick pass through Salt Lake again on the way into Wyoming.

The drive would then take me up through western Wyoming through some particularly noteworthy paleontology museums and fossil sites such as the Wyoming Dinosaur Center in Thermopolis, before entering Montana, passing through Bozeman toward Glacier National Park, the northernmost end of the route. From Glacier, I was going to turn onto the homestretch, driving southeast towards the Black Hills of South Dakota, and along US-20 in northern Nebraska with stops at the Agate Fossil Beds National Monument in northwestern Nebraska and the Ashfall Fossil Beds State Historic Park in northeastern Nebraska.

It was going to be a long drive, half of the summer, seeing as much of the American West as I could. Naturally, the plan was scaled down considerably, from a whirlwind 1.5 month odyssey to an 8 day tour of Colorado and Utah. As it turned out, my Dad was happy to join me on this trip, and has proved to be just as great a traveling companion as I remembered from our many family road trips in the Midwest and out to Colorado between the 1990s and 2010s.

We left Kansas City early on Saturday morning, 5 June, making it across the Great Plains on I-70 in Kansas and eastern Colorado without much trouble. We arrived in Denver around 16:00, making our way through the city streets to our hotel in the Capitol Hill neighborhood without too much trouble. After Chicago, Kansas City, and St. Louis, Denver is perhaps one of the cities that I’ve spent the most time in. From 1997 to 2005 my parents and I would pass through Denver on our way for a week up at a dude ranch in Pike National Forest. The Mile High City has served as a gateway to the Rockies for millions of tourists and locals alike, and it remains one of my favorite cities in this country.

While I’d hoped the trip would be a welcome break from regular life, an exciting adventure into a part of the country I’d wanted to get back to for a long while, I brought with me some of the troubles of regular mundane life, namely in a cold that was borne out of my allergies. I woke up on the morning of Wednesday, 2 June to find my throat had been dried out over that night by the ceiling fan in my bedroom in my parents’ house. I hoped the consequences wouldn’t be too bad, and certainly I’ve had worse iterations of this particular malady, but knowing it wasn’t COVID, especially considering I’ve already been vaccinated, I figured I’d be safe to travel, as long as I wore a mask whenever indoors or around other people besides my Dad. It’s meant that I’ve stuck out like a sore thumb in many of the smaller towns that we’ve stopped in for fuel and food, but for everyone’s sake, I’m fine with it. That being said, I was looking forward to seeing if the mountain air might help my sneezing go away quicker, which it could be said has worked. Nevertheless, this isn’t the most pleasant way to travel to say the least.

Denver

Denver remains one of my favorite American cities. It’s been so tightly connected to some of my favorite childhood memories, namely our annual family vacations in the Front Range, that it’s honestly one city I’d be happy to move to for work after I’ve finished my doctoral work in Binghamton. I’d trade the Appalachians for the Rockies any day. Like many of the cities and towns we’ve traveled through so far, Denver started as a frontier town, built by American settlers heading west into Colorado from the Midwestern and Northern states in the years just before the Civil War.

In some ways, it’s refreshing in an odd way to be in such a young city, yet a city that has it’s own sort of maturity. I’ve often thought that this may be how an Australian city like Melbourne feels. Even Kansas City feels a bit older than Denver. Sure, the modern City of Kansas City was founded by American settlers in 1839, but it was built near the site of an older French colonial trading post. Colorado may have its Spanish colonial heritage, but that seems to be much more strongly centered in the southern parts of that state near the border with New Mexico. The Denverites certainly have done better for themselves than we Kansas Citians have done, though that may be in part thanks to the prosperous mining economy and the immense natural beauty of the Front Range, both of which Kansas City’s own economic might and natural beauty aren’t easily or fairly comparable to.

I’d hoped to do a couple of things while we were in Denver, though my fairly constant sneezing kept our trips out of the hotel room slightly less frequent than I’d have hoped. That said, on the first night we were there we did go to an Indian restaurant on 6th Avenue, called Little India, which was a good remedy for my condition. I don’t have much of a toleration for spices of any sort, as many people who read this can attest to, but even the assuredly mild buttered chicken that I ate, with a cup of tea for good measure, were immensely helpful in trying to fight off this sneezing. That evening, well fed and ready for an evening in, we turned to our respective devices, my Dad to a book, myself to some reading about the local area, planning out our Sunday.

The following morning came early. We’d planned on going to the Corpus Christi Mass at St. Ignatius that morning, but discovered at dinner the evening before that because of the pandemic they were only taking RSVPs up to the Wednesday before each Sunday, so we ended up staying in. That said, we still woke up early on Sunday, 6 June, to watch the Formula 1 race from Baku, the Azerbaijani capital, with all its unexpected twists, turns, and tire failures that made it one of the more memorable races of the season thus far. After watching the race, I went out to a nearby grocery store to get some more tissues and a box of Earl Grey tea bags.

As lunchtime came around, we left the hotel for the day and drove up towards Downtown Denver to walk up the 16th Street Mall. It was a really nice day at first, though as the Sun came out from behind some clouds we felt like we were being cooked. As of when we left Kansas City, the weather still hadn’t gotten quite as hot as it has been on this trip, though I’ve heard it is just as hot back at home now as well, with temperatures regularly around 30ºC (86ºF) and above. It was nice being back in the heart of a major city again. For me, it’d been well over a year since I’d been in such a setting, in my case walking around Manhattan during the American Historical Association’s meeting in Midtown in January 2020. And while things aren’t yet “back to normal,” whatever that may mean, there was a sense of calm in the air that the pandemic was beginning to become a bad memory, that we were almost out of the woods.

We walked up as far as Denver’s Union Station, the region’s main railway terminal, and a place that seemed like a good spot for meeting people for any meal of the day. I was impressed with the quality of Denver’s RTD light rail and commuter rail services that operate out of a beautiful modern train shed behind the station. It’d be nice if Kansas City can build a system like that someday. After leaving Union Station, we decided on getting lunch at the Smashburger location on 16th Street, a place where funnily enough I’d stopped for dinner the last time I was in Downtown Denver before a Rockies game in 2013. After a good lunch, and with time running out before our only truly scheduled event of the day, we made our way back to the car, which we’d parked at the southern end of the mall near the Colorado Capitol building.

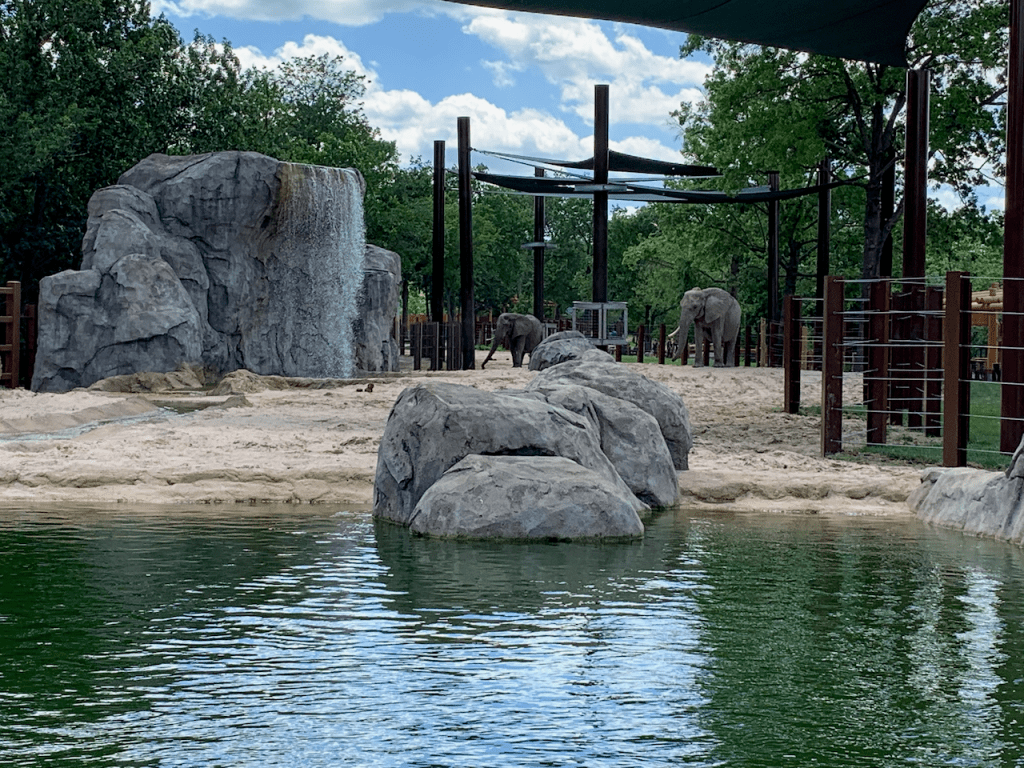

Our next destination was the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, one of the finest natural history museums in North America. We came here only once before in July 1999 when I was 7. I’d remembered the Tyrannosaurus Rex skeleton in the main lobby, and diorama halls on the 2nd and 3rd floors, but that was essentially it. The museum proved to live up to its excellent reputation, and is a clear sign of how important Western North America is to dinosaur paleontology, after all many of the best fossil beds around the globe can be found in the Western US and Canada. I was particularly struck by how this museum, while certainly gearing aspects of its displays to the youthful audience that most famously frequents natural history and science museums, also offered narratives and information about its collections that prompted further questions from my Dad and I about both the animals on display and on the displays themselves.

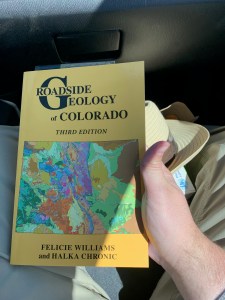

After leaving the museum, we drove back to the hotel and spent the evening resting up for the next day’s drive, which would prove the be the hardest yet. I spent the evening watching a really interesting documentary miniseries from NOVA called “Making North America,” which premiered in 2015, and discussed the geological, biological, and human histories of this continent. I figured it’d be a good refresher before we headed west through the Rockies and onto the Colorado Plateau, where many of these same themes would come directly into play in the landscapes we travelled through and the rocks we’d see along the way.

Dinosaur National Monument

I’ve always been fascinated by maps. When I was little, I used to spend hours in the back seat on road trips staring at maps, memorizing the routes of the Interstate highways, a trick that’s come in handy time and again, and looking for places I’d want to someday go. One of those places has always been Dinosaur National Monument, a vast upside-down T shaped area of federal land straddling the northernmost reaches of the Colorado-Utah border along the Green and Yampa Rivers.

I always thought it was neat that there was a national monument set aside specifically to preserve a place rich in fossil finds. Of course when I was little, I imagined that maybe, just maybe, Dinosaur National Monument might be some sort of real life, high altitude desert version of Jurassic Park, but as neat as that would’ve been, I doubt many of the cows we came across while driving through the parkland would’ve been allowed to graze free range there had the park also been home to the descendants of that T-Rex on display in the lobby of the Denver Museum of Nature and Science.

We left Denver around 08:00 on the morning of Monday, 7 June. This time I was behind the wheel, and my Dad taking the co-pilot duties. I made the arduous drive west out of Denver on I-70 through the Rockies. Over the last few years, I’ve gotten a fair amount of experience doing winter driving in the Appalachians around Binghamton, and in Central Pennsylvania, but even that doesn’t compare to the pressures of driving down I-70 through the Rockies for the first time.

I’d been on this route before, in July 2018 when my Mom drove us to a family reunion in Breckenridge, so I knew most of what to expect on the route, but I certainly wasn’t prepared to use my breaks when I should have. This came into particular note once we left the Eisenhower Tunnel at 11,158 ft (3401 m) and proceeded far downhill towards our exit at Silverthorne. I should have started breaking when we were leaving the tunnel, but waited about 10 seconds, by which point my Mazda was moving fast enough that its breaks were quite unhappy to be forced into hard service as I tried to slow us down enough to come to a stop at the base of the Silverthorne exit.

At that point, after stopping for fuel at a 7-11, we switched roles and my Dad drove for the rest of the day up CO-9 to US-40 in Kremmling, Colorado, at which point we continued on westward across the Continental Divide again at the Rabbit Ears Pass which led us down into the Yampa Valley, home to the resort town of Steamboat Springs. We spent much of the rest of the day’s drive in the Yampa basin, rising in elevation again as we made our way west of Craig, Colorado towards the canyons that characterize the Colorado side of of Dinosaur National Monument.

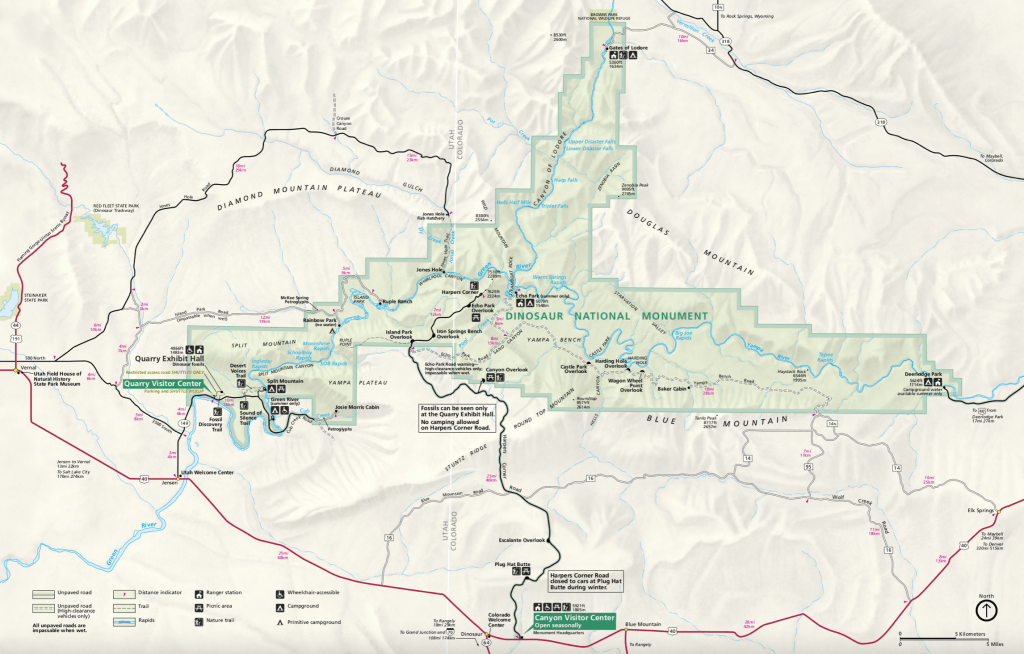

After a good two hours of driving from Steamboat Springs, we began to see roads and features shown on the official National Parks Service map of Dino as we’ve come to call that national monument. Soon, we came to the main road leading into the park’s Colorado side, and decided to go exploring and see what we could see. The road itself is 31 miles (50 km) long, and rises up to a point where I’m told you can see the confluence of the Yampa and Green Rivers and their respective canyons. While we didn’t make it quite to the end of the road, we did see some awe inspiring canyons and buttes rising and falling to the rim of the Unita Mountains to the north. I’d wondered if I might have flown over these very canyons before, on a 2018 flight from Oakland to Kansas City, something which may very well be possible considering the more recent flights undertaken on that route.

As much as we were awed by the natural beauty around us, my Dad was tired of driving, and I was ready to find a nice sofa to lay down on and see if my sneezing would subside. We made our way back out of the park, and drove again west on US-40 across the border into Utah to our hotel in the region’s main commercial center, Vernal. Our hotel room in Vernal turned out to be much nicer than the one in Denver. It seemed to be pretty new, and was your typical sort of national cookie-cutter room you’d expect from a national hotel chain. I personally prefer to stay in places like this, where I know what to expect in every room, after all it’s just where I’m going to sleep, and not the main attraction of the trip.

That evening, we had dinner at a local Italian restaurant, Antica Forma, which was actually better than I’d expected. My thinking about the local cuisine in the high deserts of northeastern Utah was some sort of a mix of Mexican food with your typical heavy meat and potatoes western American cuisine that you find in steakhouses. And while that sort of stuff was all around us, we didn’t end up trying much of it at all. Meals tend to be more of an afterthought for the two of us, something we eat, but usually something we decide on at the last minute, a far less appealing attraction than the natural landscapes or museums or galleries we travelled to see.

Our main reason for traveling to Dino was not only to see the famous fossil quarry, but also to spend an evening out under the stars with a telescope we borrowed from my Aunt Emily. We’d talked about going out into the monument that Monday night and setting up some chairs and the telescope on a turnoff along one of the main roads, but ended up deciding to stay in and rest up for the following evening. Instead, my Dad read his book and I watched the film The Dig starring Ralph Fiennes, a film about the discovery of the Sutton Hoo treasure in Suffolk in 1939.

The following morning, my Dad suggested I go to the local urgent care to see if the doctors there could suggest a more effective treatment for my sneezing than I’d been using to date. The visit proved enlightening. Not only did they confirm again that I didn’t have COVID (hurray!) but the PA prescribed a new medication which knocked out much of my symptoms almost immediately upon taking it. I was still sneezing, but now on a half-hour to fifteen-minute rotation, not on a 1 minute rotation.

We then drove back out to the monument, this time to the main entrance on the Utah side, to visit the famed fossil quarry. I’d spent a lot of time in the weeks leading up to this trip learning the roads leading into the Utah side of the monument, learning the route so that when we drove it late at night in the dark we’d have less chance of getting lost along the way. That said, it was nice seeing these roads in person after looking at so many satellite images of them on Google Maps. Whereas the Colorado side seemed to be open to just about anyone to enter and drive around on the roads as they pleased, the Utah side was staffed with a gatehouse, where visitors were able to pay their entry fees for the park. I purchased an $80 America the Beautiful Pass, which grants the holder complimentary entry into all federal recreational lands, parks, and monuments during operating hours. This, plus our reserved timed tickets to visit the fossil quarry meant we were all set and ready to go when the open air zoo tram arrived to pick us and some other groups and families up at the visitors’ center for the mile drive up the hill to the fossil quarry.

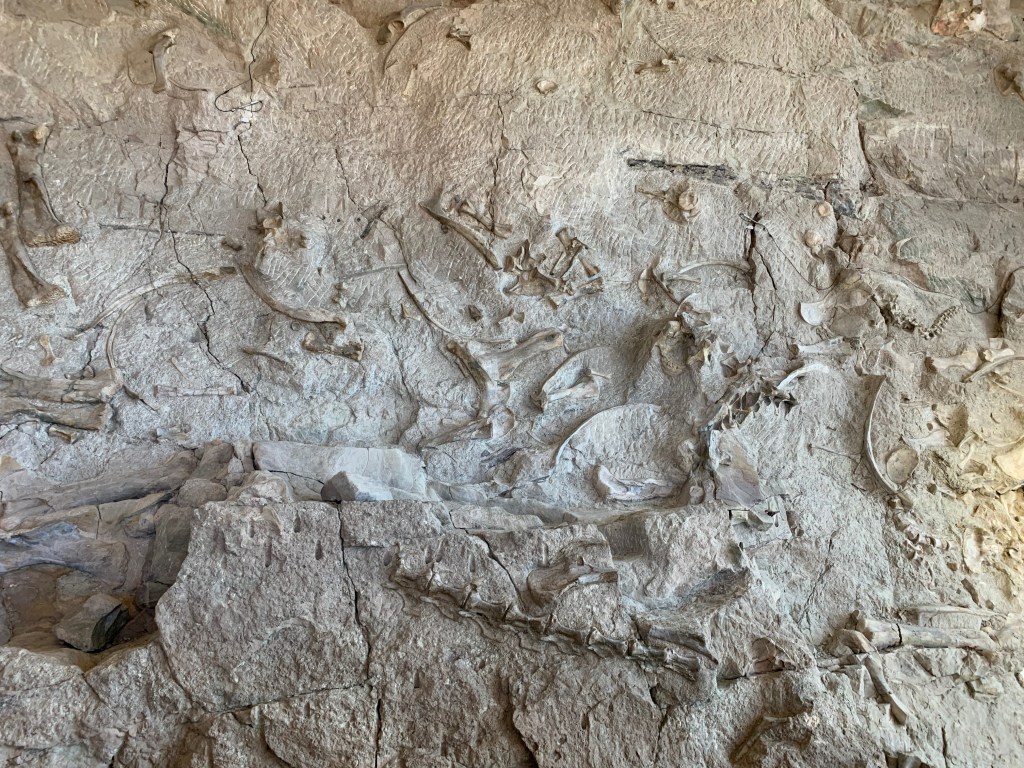

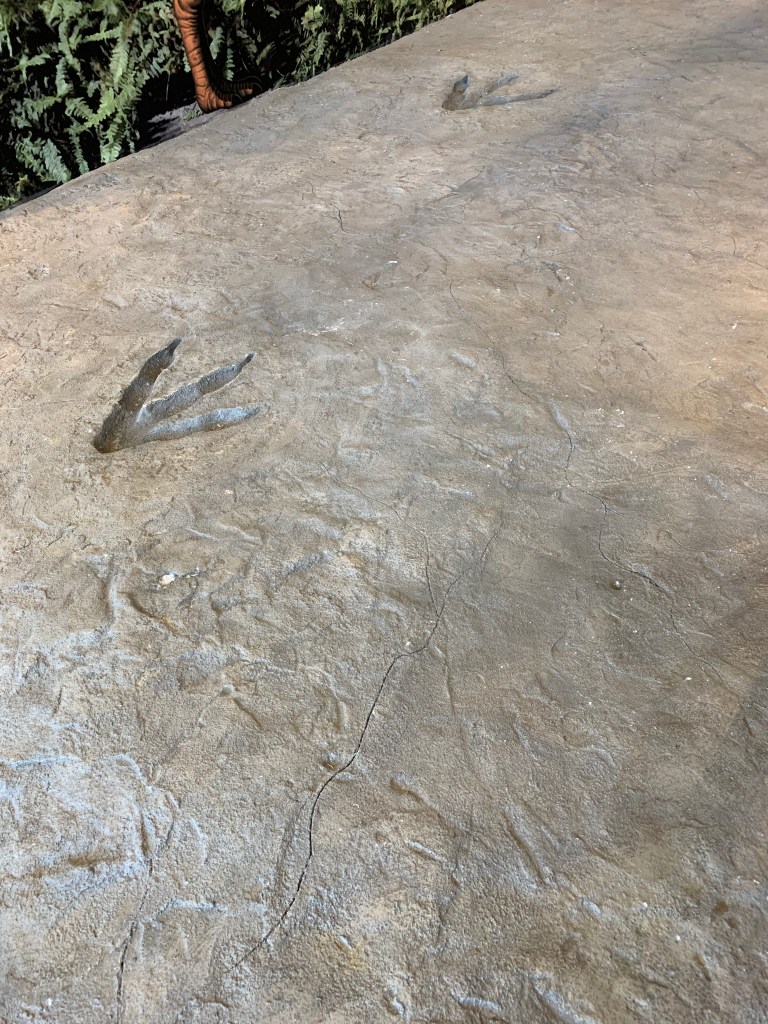

What amazed me the most about the quarry was how it was quite literally dug out of the rock. The building we were standing in, first built in the 1950s and recently renovated in 2011, was a beautiful glass and steel structure, sheltering the exposed fossils while keeping everything open to the views outside. And yet, in 1909 when the paleontologist Earl Douglass first arrived at the site of a fossil find in that distant part of Uintah County, Utah, the fossils we saw at our eye level were well beneath the surface, covered by tons of rock that has over the last 112 years been methodically removed to reveal more bones long forgotten. Many of the fossils dug up from Dino have made their way into some of North America’s finest natural history museums. Some, including those in Denver, New York, Pittsburgh, San Francisco, Toronto, and Washington, DC, I’ve had the opportunity of seeing on display over the years. It was exciting to be in the place where those fossils were discovered, to see the source so far from the great museums they now reside in, where they originally came from.

After visiting the fossil quarry we drove from the visitors’ center down the main road on the Utah side of the monument to see the petroglyphs at the Swelter Shelter, a rock outcrop along the road, UT-149. These petroglyphs, rock paintings, were made a thousand years ago by the ancient Fremont people, an Amerindian nation who lived on the Colorado Plateau up until around the beginning of the 14th century CE. Named for the Fremont River, which itself was named for the 19th century American explorer and military officer John C. Frémont, the conqueror of California, these people are only known through their archeological remains. The petroglyphs appear to show human figures with antlers, not unlike some ancient Celtic art, yet drawn in a manner fitting to the desert environment within which they were created. Ancient American art is one area that I’m woefully unfamiliar with, though hopefully I can rectify that eventually. A day not spent learning is a day wasted.

After viewing the petroglyphs, we drove further into the monument up UT-149 to see which of the two overlooks on the Utah side, Split Mountain and Green River, would work best for that evening’s stargazing. We first drove to the overlook above the Split Mountain campground and decided that the large mountain face just across the Green River from us might prove too much of an obstruction for our needs. After this, we turned around and drove to the next overlook, this one above the Green River campground to the south. The high rocks surrounding this one tended to be further away, and less obstructing of our sight-lines, so we figured we’d try that site out later at sunset.

Returning to Vernal, after lunch we settled in for a restful afternoon. Dad continued reading, and I watched part of Eisenstein’s classic 1938 film Alexander Nevsky; the Battle on the Ice scene came up as a suggestion on my YouTube home page. I moved from Nevsky to other fairly mindless shows, forgetting about the couple of months worth of National Geographic and Smithsonian Magazines I’d brought with me, having been forced to put them to the side while I read for my comprehensive exams this Spring. That evening, while my Dad had leftover pizza, I walked across the parking lot to a local Cantonese restaurant and picked up my own dinner.

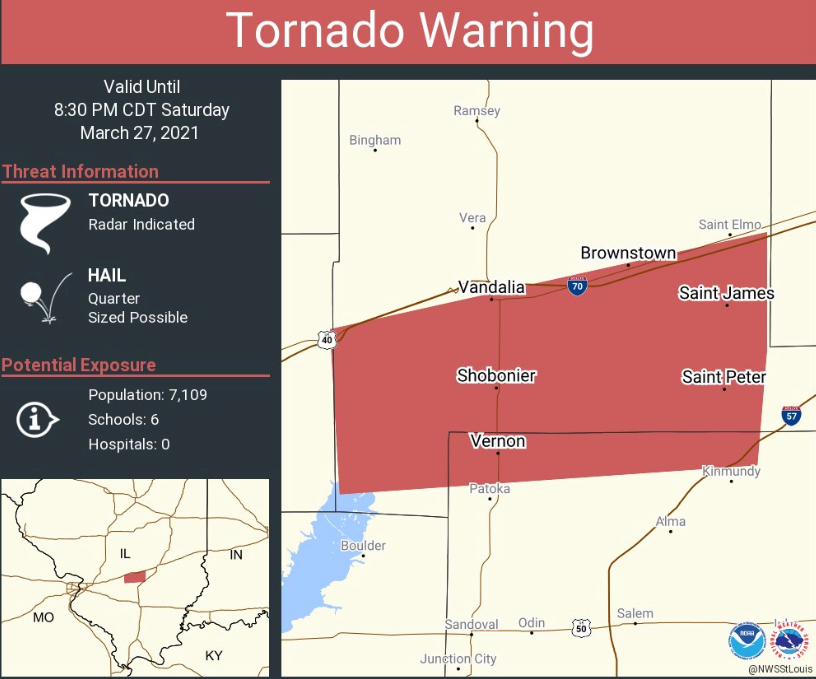

Being well fed, at 20:00 we got back into the car and made our way east out of Vernal toward the canyonlands of Dino beyond. The gatehouse was unoccupied as we drove past it, and up the road to the campgrounds beyond. We took our spot at the overlook above the Green River campground by 20:43, 2 minutes before official sunset, and set up the telescope, chairs, and cooler by 20:53, with just enough time to spare to watch the sunset in the west. Unfortunately, as we drove out of Vernal we were met by a line of whispy clouds that seemed to be moving west to east over the monument and our site. These clouds made the stargzing far less illuminative than we’d hoped, but we still saw far more than we normally would’ve at home in the city.

The first light to appear in the sky seemed to pop into sight like a gleaming beacon of hope on the western horizon colored with the orange glow of the setting Sun. I knew immediately what it was, Venus, the Evening Star, and celebrated its arrival with a couple quick pictures of it with my phone. We had another phone mounted atop the telescope’s view lens, hoping that’d help us position it better and maybe even take some pictures of the stars and planets we’d see, but the best we got were some photos of a rather square-shaped rock on the top of the far canyon wall.

That evening was marked by quiet conversation, long minutes staring up into the night sky at the brightest stars visible, Vega in particular. We were seated facing east, and Venus quickly descended below the horizion, itself marked by the distant ridge of a mountain range to the southwest, so we were less concerned about missing that beautiful sight than we might have been. As the night drew on, we saw more and more stars pop into our view high above us. Along with them were shooting stars, meteorites raining into the Earth’s atmosphere, and the occasional aircraft’s flashing lights appearing over the ridge of the Unitah Mountains. It was wonderful, yet at the same time we found ourselves wanting more. The cloud cover didn’t help us, and likely as this trip continues, we’ll find another time to sit back in the wilderness somewhere and look up at the night sky.

In those moments on Tuesday night, I found myself wondering who might be out there, sitting back on the top of a cliff on some distant planet looking up in their own night sky, perhaps even seeing Earth. To peer into the night sky is to see into the past, to see light that left the stars years before, light that took quite literal light years to travel to the point that it can be seen here on Earth. Yet to me looking up at the night sky is also a chance of looking into the future, a future where humanity is an interplanetary, if not interstellar species, one with peaceful, and mutually beneficial relations with species from planets throughout our Galaxy. I found the whole experience timeless, something that could very well be the same even if it takes me fifty years to do it again. I hope, and expect, it won’t be nearly that long at all.