Category Archives: Wednesday Blog

A Sunrise

A Sunrise – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

This week on the Wednesday Blog, a reflection on the rising Sun.

Last Friday as I drove south to reach my classroom in the morning I was awed by the pink and yellow rays of the rising Sun that appeared in the east. It seemed to echo some sort of hope of things to come. These last months have felt as though I’ve been caught up in a storm both unfamiliar and of my own shaping, and it has left much of my life from my part time work to even this Wednesday Blog to be written at the eleventh hour each week. Unable to set foot on solid ground over these months, I’ve prioritized staying upright in my life while putting my best efforts into my work. Still, even that hasn’t seemed to be enough to balance everything.

I am more used to the pattern of having several part-time jobs which fit together however imperfectly, so the introduction of a full-time position on top of everything else sank all those other things that I previously worked on to the detriment of all. There were weeks when I even ignored my own needs as my new duties required every shred of focus, every aspiration of my emotions. This has left me exhausted of many of the things which kept me going and I feel hollowed out by the harsh tides of the world.

This sunrise then spoke to me of hope. It was a sunrise that only the long nights of winter could forebode, a bright eastern glow whose radiance was more pronounced because it followed a long, dark night. I gazed up at it when I could on my drive south and thought of all that had transpired, and all the possible futures that these next months and years might hold. I know, of course, that the Sun appears to rise as our planet continues in its revolutionary course, the Earth spinning on its axis with each passing day so that this sunrise has surely been seen by many before and will indeed return again to grace our mornings. Yet amid all that the sciences can tell my emotions speak louder in my interpretation of its very natural phenomena.

There have been many sunrises in my life that have moved me, after all I’m traditionally far more a night owl than an early bird, so until recently I rarely saw the sunrise. In my childhood my bedroom looked out to the west and each evening was warmed in the glow of the setting sun. With all our popular fears and worries about endings today, they are far louder than any wonderings about new beginnings, it seems that we as a civilization looks to the setting more than the rising Sun. We see our future as a fading echo of distant glories, our lives existing in the ruined monuments of earlier generations. Our stories are populated with more Ozymandiases and fewer Abrahams and Jacobs in spite of the newness of so much of our built world here in the Americas and the other old settler colonies.

I think our transition from the early decades of this new century into the first of the middle decades has a great deal to do with all of this. The generations now being born will surely see the last century as something in the past existing behind a veil just remote enough to not be touched. When I show pictures from my travels of old monuments today my audience and I are both struck that often they were infants or even yet to be born in that same moment. The first decades of this century are to them what the 1970s and 1980s are to me; and as we continue our inevitable march forward in time we will move ever further away from those years and generations in which our world here in the United States, and especially here in the Great Plains and West, was still young. It seems to me that we have a great deal to learn of change; that we will always need a reminder that the passage of time is something to be admired as much as it is feared. The oldest people I knew as a child would now be reaching their centenary if they were still alive, and surely someday I too will be in that moment where the power of my life fades as my time recedes from life and into memory.

The rising Sun speaks to me then of both hope and the truth that after many sunrises there will be one which will be seen in a moment when my world and all who I know are gone. There will be a sunrise after my time, yet in the meantime I hope I can make all the days that follow the sunrises of my life fruitful. With that light there are a great many things I can see, a great many marvels to behold; for all of us are individual marvels in all our complexity, our wants, our passions, and our fears. As long as I am able, I yearn to experience those marvels like that pink and yellow sunrise from a few days ago and live to the fullest of my ability.

St. Nicholas

St. Nicholas – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

This week on the Wednesday Blog, some words about St. Nick.

We find ourselves again in the last month of the year, at a holiday that I wasn’t aware of until elementary school. According to tradition, on the night leading up to the 6th of December, St. Nicholas will come around to everyone’s houses and leave presents in our shoes. I remember thinking that was an exciting idea at first but today I wonder about the sanitation of that, let alone the sanity of it as well. Then again, to quote the late, great Chico Marx “there ain’t no such thing as a sanity clause!” I always imagined St. Nicholas as a winter saint, in line with the old Green Man figure of folklore. So, for me this feast day is more about the beginning of Advent, of December, and of the Holiday Season than it is about the sainted fellow himself.

There are many elements which go into this season that conflate the ancient, medieval, & modern, the sacred & secular, the busy & serene. I feel as though my life has been caught in a whirling storm, a tempest raised by some staffed soul seeking to prove a point about the possible and limits of my own ability. I can now sit at peace with my own limitations and know that in spite of what might be seen as a failure is its own kind of success, a fulfilled experience across eighteen weeks that proved to me where my own road leads.

This Christmas, I find myself thinking as well about the remarkable Christmases past. Christmas 2012 stands out to me now. That year, I had my one and only experience sitting beside my grandfather Kane at the table as one of the adults. He told me stories about his own childhood and twenties that I hadn’t heard before. It’s been ten years now since he made the voyage to the great Christmas dinner in the sky, where I hope we’ll sit beside each other again someday. That promise of a future may well be the chief reason why I believe at all, for belief on its own is hard to justify. I look at the charming, gregarious, and quite vocal people I’ve spent my days with now for the last few months and think about all the Christmases to come they will know. Even as our roads come to their divergence, I smile thinking about them and all they will become.

These long December nights are a time when the ancient returns to life again in my imagination; when the dancing dreams of an idealized past reignites itself with the flames that inspired our modern electric lights which keep us comfortable amid the darkness. The early mornings still feel alien, and they are something I will not miss from this time now ending, yet the fact I could make that time my own is something I’m quite proud of.

All of this is to say that I have chosen to leave the school I am currently teaching at as of the end of this semester on Wednesday, 20 December. If you couldn’t tell, I don’t often know what the conclusion of these Wednesday Blog posts will be when I start writing them. St. Nicholas may be in my mind, yet life continues to catch my attention. I set out in July to see if I could teach middle school children, ages 11 to 14, and I’ve found the difficulties outweigh the tremendous successes. I’ve learned where my abilities lie and where I have room to grow. So, I now prepare to leave as I see the wind change on the eastern horizon. Like the staff-bearer, this role “I here abjure,” and leave it happy at the fortune of having held it if only for a while so best to speak the truth as I know it. This moment will one day be another person’s ancient history even as I now see the present moment; and when it is their history, I hope they will see all the interwoven vines and threads which connect this moment with its own historic foundations and see all the things that from it are yet to come.

Like St. Nicholas’s Day, these months serving as a teacher have touched on a great many historic rhymes, and I hope moments of it will live on as another one of my own Christmas memories.

Tools and Eyes

Tools & Eyes – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

This week on the Wednesday Blog, how we enhance our vision with innovation.

When I was 5 years old, I remember one Spring afternoon as the Sun was beginning to set when my friends and I were still at our school in the Chicago suburbs out climbing on the playground. I was near the top of the play structure when I saw a car pull in and a woman climb out of the passenger’s seat. I recognized the car and the figure coming towards me and excitedly climbed down from my perch to greet my Mom, thinking she’d gotten off work early and was coming to pick me up at the end of the day. As I got closer to the woman, I was shocked to see it wasn’t my mother but someone else.

Two years later, during my first March in Kansas City we had state-mandated vision and hearing tests in school at which time I was sent home with a note for my parents that my vision was poor enough to require glasses. I got my first pair on 20 March 2000 at a shop in Oak Park Mall and have remained bespectacled every day since. It amazes me somewhat that I remember the day like that, or that I can remember it was a sunny 56ºF that day, yet there you go. I’ve probably gone through 20 or more pairs of glasses, or speclaí as they’re called in Irish, in the years since. For a while I was getting a new pair each year, though in recent years I’ve deferred that insurance benefit to use it only when I absolutely need new frames.

Still, one recurring feature of the quieter moments in my life since that sunny Monday just after the turn of the new millennium has been that my world changes each night when I set my glasses aside to sleep. For the longest while I would have dreams in which dimensions didn’t match my expectations––rooms that were long and slender and filled with cartoonish clutter, buildings that seemed comically curt in their width that I could surround them with the fingers of one hand, held up before my eyes.

These visions remained in my dreams alone until after our move to Kansas City. In those first bespectacled years I began noticing my dreams seemed to come to life before my own eyes on those nights when sleep evaded me, and I lay awake without my glasses for hours on end. Lights and colors seemed to blend in unfamiliar ways, echoes of things I knew from the daytime danced before my eyes when I should’ve been asleep, and shapes never were quite what they seemed.

Without my glasses, the eyes I use to behold all that I have known in these last 23 years, that reality seemed to burn away on whisps of air. I’d imagine the faces of people I knew into being before my eyes and see them in strange ways that my limited vision could allow. Yet throughout this process I found all of this strange, for I knew what these faces and places looked like. My eyes and my mind could not work together as they once did now that my eyes relied on lenses to see.

How then would we react if all the creations we’ve devised were taken from us and we were left with our natural abilities alone to survive? Without glasses, my world would be quite different. I would likely have known my parents’ faces differently than I do now. The course of my career is as much defined by my access to information thanks to the internet and computers as it is by what was available to me as a child in the early 2000s when I had a computer that was linked to a far less interwoven internet. How would we’ve handled the pandemic differently if we lacked the quick transportation between continents, let alone the ease of spreading information within our own countries to stay at home, wear masks, and such in 2020? Certainly, air travel helped spread the pandemic across the planet faster, yet to the rest I’m unsure what to say.

In the middle of the last decade, I grew so used to my transatlantic connections that seeing those largely stripped away in 2020 left me feeling this sense of isolation that reminded me of the incomplete interpretation of the world by my unspectacled eyes. I grew further and further distant from my old life and developed new attachments here domestically that I’d not noticed before. For one, I stopped watching Doctor Who in 2020 and started watching Star Trek, moving from a show produced in Wales to one in California (and now also Canada) as my main source of escapist entertainment. Now again, having physically returned to Britain, my mind keeps returning there during the quiet moments.Yet those memories are inherently incomplete, filtered by a vision begotten by wishful intent to return to something long left behind. Like my moments each night gazing out before I drift off to sleep on a scene lacking clarity yet filled with enough quirks to keep me focused, and yes entertained. After all, what are our memories for but to keep us company in those quiet moments, a sort of built-in cinema in which the documentary features are about our own pasts, the blockbusters those stories we create just for ourselves. Some of those will find their way onto paper and maybe out into the world for others to one day read. Without all of the tools we’ve created, those stories would take much longer to travel far, and would see their fullest life in their original telling for us alone.

Sixty Years

Sixty Years – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

This week on the Wednesday Blog, recognizing the sixtieth anniversary of the assassination of President Kennedy.

Bill Clinton was the first president who I can remember, and like many other millennials my perspective on the Presidency is shaped by his two terms in office. Yet beyond the immediate I always knew several other presidents: Lincoln (as I often write), Washington, Truman, and Kennedy. Of all of these, John Kennedy is the most complicated; he was the first Irish American Catholic to be elected to the White House and his picture was still pretty common in houses even into the turn of the millennium. His term is remembered most nostalgically of all the presidencies of recent memory for how short it was and abruptly it ended.

As much as I always knew who the Kennedy brothers were, I also knew that Dallas was the city where President Kennedy died. When I first visited in my adolescent years, I made a point of going to visit Dealey Plaza and see where it all happened. Every year on this day I find myself thinking of what happened there 29 years before I was born. It’s strange how much events that are relatively removed from my own lifetime still have such an impact on how I see things. For me the recent past still goes back to the turn of the twentieth century when the world that I was born into in the Midwest was being created. So, as far as the assassination of President Kennedy is from my own life, those 29 years still have never felt that distant.

Today, this particular anniversary is striking to me because it is becoming more distant. 1963 is now a full 60 years removed from our own time, and as I look ahead the middle of this century seems closer than I ever imagined before. The passage of time could well drive people to fear for their own mortality, and to a certain extent I find those thoughts enter my mind now and again. Yet when I worry about my future it’s less that I will lose something of myself with the passing years and more that the memories I’ve grown up hearing and those I’ve written for myself will become ever more remote from my lived experience.

For the last several years I’ve found myself caught by a faint memory of a sort of reddish glow. I’ve known it originated at some point in the early 2000s, about 20 years ago for those who are counting, yet beyond that I could only speculate. I figured there might’ve been some phase of interest in Renaissance Italy in the books or documentaries my parents were reading or watching around that time, yet I couldn’t remember any specifics. Then, several weeks ago, I remembered some faces along with that red glow and it occurred to me that what I’ve been longing for was a particular day, Thanksgiving Day 2003.

That year, my Kane grandparents and great-aunt Sr. Therese came down to Kansas City to attend my Webelo bridge-crossing ceremony when I graduated into the Boy Scouts. They patiently followed my parents and I around town, attending a weeknight fencing lesson of mine (I used to fence saber), and joining all of my maternal Kansas City relatives for Thanksgiving dinner at the farmhouse that my parents built. We lived on 34 acres of land in western Kansas City, Kansas and one thing we all miss about that house is the view to the west out the back windows. The sunsets were gorgeous. That Thanksgiving was a clear day with light clouds in the sky and as dinner was nearing completion, I remember sitting with my grandparents and Sister (that’s what we all called my great-aunt) in the living room with something on the TV, but our eyes were drawn to the sunset out the window.

The backside of our house was all one big room, to the right was the kitchen, in between the kitchen table, and to the left the living room, and in the kitchen, we had these beautiful imported red Italian wooden cabinets which my parents saw on This Old House and bought in a stall at the Merchandise Mart before we left Chicago. The beautiful shades of red that I remember are of the sunset shining off of those cabinets, a true marriage of nature and craft that I hope I will never forget.

My Kane grandparents and Sister are all gone now, the only ones in the room at the time that memory occurred who were alive when President Kennedy was killed, yet for all of us that moment marked our time as one of uncertainty. Now, as an adult I appreciated Jack Kennedy still, yet I would’ve rather voted for his younger brother Bobby. I see more of the nuance in those colors even when as a child on Thanksgiving 2003 all I saw was bright light that made me uncomfortable.

Sixty years isn’t that long, and yet to an extent it really is. Sixty years before President Kennedy’s assassination the country was recovering from President McKinley’s assassination, a bleak start to the twentieth century in a moment of triumph and seeming progress. It’s all about where we stand in the great cycle of years. I like the old adage that the Greeks saw time differently from us, that they stood looking towards the past with the future behind them. We don’t know what will happen in the future and our pasts and those of our parents and grandparents really shape our worlds in far greater ways than we can often imagine.

The End of an Era

The End of an Era – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

This week on the Wednesday Blog, my perspective on the last century and a half as a time of tremendous change.

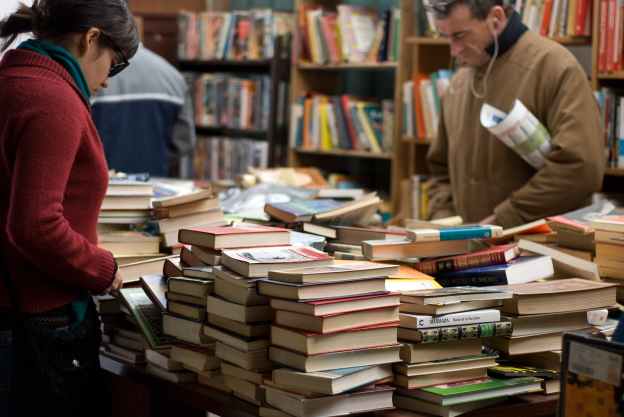

On my first day in London this October I walked from the British Museum, my first stop in the capital, to Charing Cross Road where I made my way into Foyles, my favorite bookstore in that city. Foyles has a wider variety of titles than I’ve seen in most bookstores, and especially titles that catch my attention time and again. I didn’t plan on walking out with a new book, and I stuck to that plan, yet I saw several books which I’ve since acquired in other ways since I got home (I do kind of feel bad about that.) I didn’t pack for this trip with new acquisitions in mind, leaving little room for anything new in my luggage.

Still, I loved wandering through the aisles and shelves of Foyle’s and catching up on the latest that the British publishing industry has to offer, five years after my last visit to that island. Here in the United States, I see some reviews of books printed in Britain, usually in the New York Times or through interviews on NPR, but by and large I’d cut myself loose from the British press that I read, listened to, and watched throughout my adult years. Unlike previous trips back to London, a city that became a home-away-from-home for me in 2015 and 2016, I felt like I’d missed a great deal and had a lot of new things to discover on this trip.

One book that caught my eye several times was Michael Palin’s new book Great-Uncle Harry: A Tale of War and Empire which tells the story of the author’s own great-uncle Harry Palin whose life saw the end of an era and the beginning of our own tumultuous time. Harry Palin was working on a farm on the South Island of New Zealand when Great Britain and its Empire entered the First World War in August 1914 and enlisted with the New Zealand Expeditionary Force, one-half of the famed Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZACs). The elder Palin survived the Gallipoli Campaign and for a while on the Western Front until he died during the Battle of the Somme in 1916.

Two weeks after seeing Great-Uncle Harry on the shelves of Foyles I was reminded of it by something else and bought a copy of the audiobook on Audible to listen to, read by the author, in the car on my way to and from the school where I currently work. The life and story of Harry Palin animated my drives to and from the school where I now work over the last two weeks and left me both inspired to think about the end of the nineteenth century, a period in our recent history that I’ve always been fascinated by, and horrified by what became in the twentieth century.

I chose to not study the end of the nineteenth century and turn of the twentieth century professionally because of the looming specters of the World Wars ever on the horizon of my memory of those moments in history. Harry Palin’s story reminded me of what I love about that period as much as at the end of his life what horrifies me about the experiences of his generation.

The world that existed in 1914 was one which had a continuity with the generations that came before it. There were some major shifts, the revolutions at the end of the 18th century and in 1848 come to mind, yet none of those in Europe were permanent. The needle of change wavered throughout the century leading up to the First World War. All of that changed as old institutions, which had long weathered the storms and basked in the sunshine of Europe’s history now collapsed under the tides of change released by the hands of their own officials. That war is perhaps the greatest example of hubris among any political leaders yet seen in our long history. Men who thought they could expand their empires, enhance their prestige and honor by waging war against each other instead lost their crowns and left millions dead in the wake of the conflict they unleashed.

When I read histories of this period, I often want to shout at the characters to look out, to be wary of what is coming; for in a Dedalian way I worry we can become too complacent and hawkish yet again. Our caution is well learned, now after a century which saw two world wars and countless other conflicts born from those furnaces. In the wake of the first war a great instability allowed for experimentation to occur. This is a natural thing, something I see in the Renaissance and Wars of Religion (the period which I study) yet in the context of the twentieth Century it marks something far darker. This experimentation in politics and economics led to a further world war in which the three new dominant ideologies –– communism, liberal democracy, and fascism –– collided. Out of it, fascism fell but not before taking millions with it, and a cold war simmered which defined the rest of the century.

In my own life, a further reduction in the formalization of conflicts has played itself out. Now instead of great armies facing off in large-scale battles like those known in the world wars, or even the proxy wars fought by the superpowers we see violence wrought through terrorism. The front lines are not so far away when the threat of violence, whether foreign or domestic could be around the corner. Our children practice for the possibility of an active shooter in our schools because such an incident has happened time and again, and I’ve internalized the reality that in my profession I’m likely to experience such an attack as long as I continue to teach.

I go to places like Foyles to get away from these worries and horrors, to discover new ideas and ways of looking at the world that I was previously unaware of. On this trip, it occurred to me several days before my return to London that I was left bereft of worries, a feeling of calm that I hadn’t felt in a very long time. It almost left me feeling a loss for something I’d long known. I chose to work on a time period further removed from the present to have a refuge in my work from the horrors of the recent past that shaped my world; yet this is still my world, our world, and for as many problems as it has there is a lot that I feel nostalgic for about the century now passed. Even as I write now in 2023 and will likely be remembered as a voice of the twenty-first century, I will always think of myself just as connected to the twentieth, in which I was born and during which a great many of my formative memories occurred.

It occurs to me now that as much as we live in a continuation of the new era born out of the First World War, perhaps the general crisis we find ourselves in now, from the wars my country fought throughout my teens and twenties to the climate crisis we now witness, is bringing us into an even newer era. I hope it will be better than the last, and that maybe this time we’ll find a way to live up to the highest ideals of our predecessors.

Standard Time

Standard Time – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

This week on the Wednesday Blog, I argue that we should stick to Standard Time.

I missed the switch to Daylight Savings Time this year as I was in Puerto Rico that weekend which doesn’t do the time change, meaning we went from being 2 hours ahead of home to just 1 on the night of our return journey. So, my usual annoyance at the transition to Daylight Savings Time, and the hour lost in the process, wasn’t as severe. Yet as we return to Standard Time after a long summer I have some thoughts about why we ought to stay where we are now.

It baffles me that “Standard Time” lasts only 5 months, though it doesn’t feel that long, while Daylight Savings Time, or Summer Time as they call it in Europe, lasts during 9 separate months from mid March through early November. Daylight Savings has effectively overrun the calendar, leading to the calls in March for us to permanently adopt DST as our new standard, year-round, time.

I had no major complaints with this proposal earlier this year, though I figured that Standard Time is probably closer to the natural solar time than Daylight Savings which fiddles with the clock like a crafty accountant. All that changed when I began to leave home before dawn for this new teaching job, and I found myself barely seeing the morning sun on most days. As we returned to Standard Time this week I’ve felt far happier leaving home in the early dawn hearing the birds whistling away in the trees, welcoming the new dawn as they do.

I may not feel quite as euphoric as Edvard Grieg’s “Morning Mood” from his Peer Gynt suite would evoke, yet I am much happier seeing that Sun high in the sky above me as I begin my day. So, let’s make Standard Time the default and eliminate Daylight Savings, as those two time changes each year cause such a bother.

I find that our cities have long been built to be seen more at night amid the glow of streetlights than during the daytime. We gain more evenings under their sway, more evenings too away from the city lights to gaze up at the stars high above us. I’m fine with the Sun setting so early in the evening. I’ve lived in cities where it sets far earlier than it does Kansas City in winter, and there’s something about that which evokes a sort of seasonal sense of nostalgia in me, a memory of Christmas and all the other midwinter holidays to come.

Standard Time is as close to our original local solar time as we’ll be able to get. Not that long ago, each city and town had its own time based on its own local noon. I’d rather have our clocks tick closer to that local noon than not. Consider this my vote.

A Return

A Return – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

This week on the Wednesday Blog, some words about a trip just completed.

My world is one of open borders, the international scholarly republic of letters, and friends far and wide in this country and across the oceans. All of that shook to its core in 2020 when those borders closed, and friends grew apart with the pandemic we all experienced. I attempted to keep my life going in 2020, in those last few weeks before COVID-19 changed everything with a quick trip to Munich to see some university friends. Thereafter, for the last three years I kept to our own shores. A part of my wariness to travel far was a lingering worry that those borders could close again, that as I feared in 2020 so too even now there was a chance of getting stuck far from home.

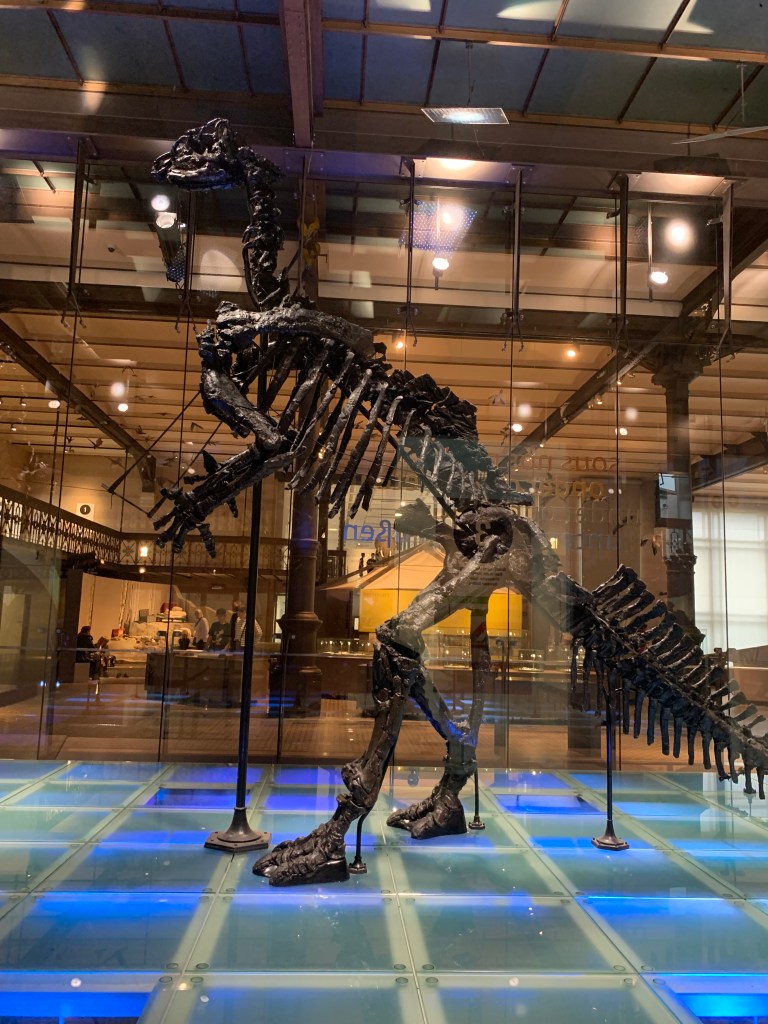

Over the last two weeks of October, I saw past that worry and made a joyous return to Europe, visiting Brussels, Paris, and London not just as an American tourist but as a historian hoping to realize dreams of walking the same streets as the humanists whom I study who lived at the end of the Renaissance 450 years ago. I arrived in Brussels on Sunday the 15th with an ease and lack of concern for doing or seeing everything I wanted to that betrayed a confidence that I’d return again in the future. And as I write this, I’m continuing with the research that will guide me back to Paris again.

In the stress and emotions of my daily life, I’ve learned to embrace the quiet moments, in which the sonorous radiance of the most joyous resurrections can be heard. That silence makes a return to places so close to my heart as wonderous as hearing Mahler’s great Resurrection Symphony in person. Why limit myself with worry when there’s an entire world out there to experience?

On this trip I found my favorite thing to do was to walk around and experience the city I was in. I did this most in Paris, when I arrived there around mid-day on Sunday, 15 October I ended up walking from Gare du Nord all the way to Notre-Dame, via Place de la République, the Marché Bastille, the Canal Saint-Martin, and Île Saint-Louis. The route took me about 6.4 km (3.7 miles) and lasted from around 11:30 until close to 14:30 when I descended into the Métro to make my way to the studio apartment I’d rented near the old Bastille. I loved returning to Paris in all its busyness, its sights, sounds, yes even smells. I was agog walking through the Marché Bastille and seeing whole fish lying on ice in the seafood stalls, there was even a shark with an apple in its mouth. If I lived in a place like this, I’d be sure to visit an open-air market every so often, if only for the experience of life that it offers. This entire walk, all 6.4 km of it, was done with a heavy backpack hoisted behind me as I didn’t think to look at Gare du Nord for the luggage lockers in the basement; use those, dear reader, if you have a long delay between arriving in a city and checking into your lodgings if the place where you’re staying doesn’t have a luggage room.

All in all, I walked 197 km (122 miles) on this trip across all 15 days. My feet are still sore, and my shoes need new insoles, yet I’d gladly do it again. Life on foot out in the open is much more personal than life behind the wheel of a car traveling at speeds at least 3 times my average walking pace. Whether in Paris, Brussels, or London, I took time to enjoy my surroundings, and to live as much in the moment as I could.

I found Brussels to be gloomier, the Belgian capital felt tired and like Paris well lived in. I was staying near the European Quarter in Ixelles, to the east of the city center and on my frequent walks back to my lodgings after dark I’d remark on how low the horizon felt walking those streets. Unlike many other cities I’ve visited, the high apartment buildings seemed to block off the lowest reaches of the night sky and the overhead glow of the city lights which illuminated the streets shaded my eyes from seeing up towards the heavens. It was like some of the stories I remember seeing as a child, stories told on the screen which were set in this sort of world where the mysteries of the skies above are darkened by a radiant yet feeble attempt at letting there be new light which makes the world all seem smaller and more confined. Far from utopian, for this light tells me I am somewhere, it still left me wanting for more and grander visions of the Cosmos far from those streets.

Returning to London felt as though I was returning to a long lost home. I strolled down the platform at St Pancras when I arrived beaming a broad smile after days unsure what I’d find or think arriving in that city. I soon found my way around the capital with ease, much of what I’d known during my life there in the middle of the last decade was as it had been. I returned to most of my old favorite places––the museums, the streets & squares of Fitzrovia, Bloomsbury, and Mayfair––and to the place where I once lived on Minories just beyond the old city walls. On my last evening there I sat for a while in the garden behind my old flat, the one my window looked out onto, and thought about all that had happened since last I was there.

I returned to Europe a different person from who I was when last I crossed the Atlantic. The Pandemic and my years of doctoral study shaped my youthful optimism just as it sculpted my ever-receding hairline. I returned to Europe less worried about losing something I had in the present and more appreciative of that moment I was in, of the places I was walking, the people I was seeing, whether for the first time ever or for the first time in years, and still hopeful that one day again I will return to these places. I do hope it’ll be sooner, whether just to visit or to live remains to be seen.

As much as this trip felt like a return to a life I once knew well, it also felt different from my past when I lived across the water because I’m a different person now. If any experience in my life could feel like a “return to normalcy” to quote Warren G. Harding’s campaign slogan of 1920 it would’ve been this; yet there is no real returning to an old normal, for we are never the same. I felt this when I returned to Kansas City after living in Europe; I was gone for just under a year, yet it felt like I had missed so much. Some things remain yet eventually all things must change. For the first time in my life, I’m happy to accept that, and to embrace that change as a good friend.

Birdsong

Birdsong – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

This week on the Wednesday Blog, I extol the virtues of listening to our bedfellows in nature.

For all our pretenses of difference from the natural world as political animals in Aristotle’s words we remain a part of the great fabric of the Cosmos itself. In those moments when we find ourselves at a loss for words, for what to do in our lives, I suggest remembering that no matter how political we may be, we are all still animals. We all still are creatures created through the process of evolution and natural selection after many generations of formation to become the species we are today. Our very nature is tied with this long distant memory of Eden, of a time when our ancestors still lived amid the flowers, the vines, and all living things.

We remember less the perfection, which seems remote to our sensibilities like some sort of a nebulous dream that will burn up as soon as the Sun of our rational minds awaken in the morning, and more the shame that ended that dream. We’ve covered ourselves all too well, with our trappings of civility, our industry, our commerce, and our shows of strength. What remains of that dream that may once have been our reality? It is but a shadow cast by a passing cloud upon the land below where we live, seeking a truth we can’t be sure is real?

Yet in those moments when I am most distressed, most beaten down by life and work, all those things I do, I try to remind myself to go sit outside a while and listen to the birds. Their joyous singing tells of another time when we too were free of the cares that we’ve burdened ourselves with. Birdsong is to us an echo of a lost world, just as the stars burning bright high above us are an echo of worlds, we imagine we might one day come to know and understand. In the great moments of sorrow and trouble it’s best to return to the purest form of joy there is. The simplest voice often has the finest chorus in this great cosmic play of life.

So, take a moment to go out today and listen to the birds and all the other wild things, for at some level we have more in common than we lack. I for one long for a day when I can sit in a garden, close my eyes, and listen.

On the Cannibals

On the Cannibals – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

This week on the Wednesday Blog, looking back to a Renaissance philosopher to try and make sense of the present.

I was in my 8th grade year when Hamas took control of Gaza, and throughout my childhood as much as my own country was at war in Afghanistan and Iraq in what our government called the “War on Terror,” I knew of Israel and Palestine as a set of nations that had been in some state of war since the foundation of the State of Israel in 1948. To hear then last week that Hamas had attacked Israel, starting a new war at the end of the Jewish high holy days filled me with a grief I thought had been lost in the jaded and bruised reactions of my conscience after decades of hearing of atrocities here at home and abroad. At one point in my life, I thought of war as a sort of grand adventure, of the glory that men like Theodore Roosevelt and Winston Churchill looked to in combat. I never chose to serve, nor would I have likely been allowed to because of my health, though as I grew up, I found the very idea of war, let alone the idea of taking another person’s life to be anathema and horrific to behold.

The Catholic Church has a theory of just war, which argues that in the case of most need, when no other option is available that war is the only solution available to a good and morally upright people. I for one have trouble with this theory, though I do see how it could make sense. I’d rather negotiate for as long as possible, try to find common ground with a potential enemy in the same way that I try to speak to those I interact with on a daily basis in their own language. Yet sometimes it does come down to this question of whether after all the negotiating and the impasses that have resulted if fighting is justified?

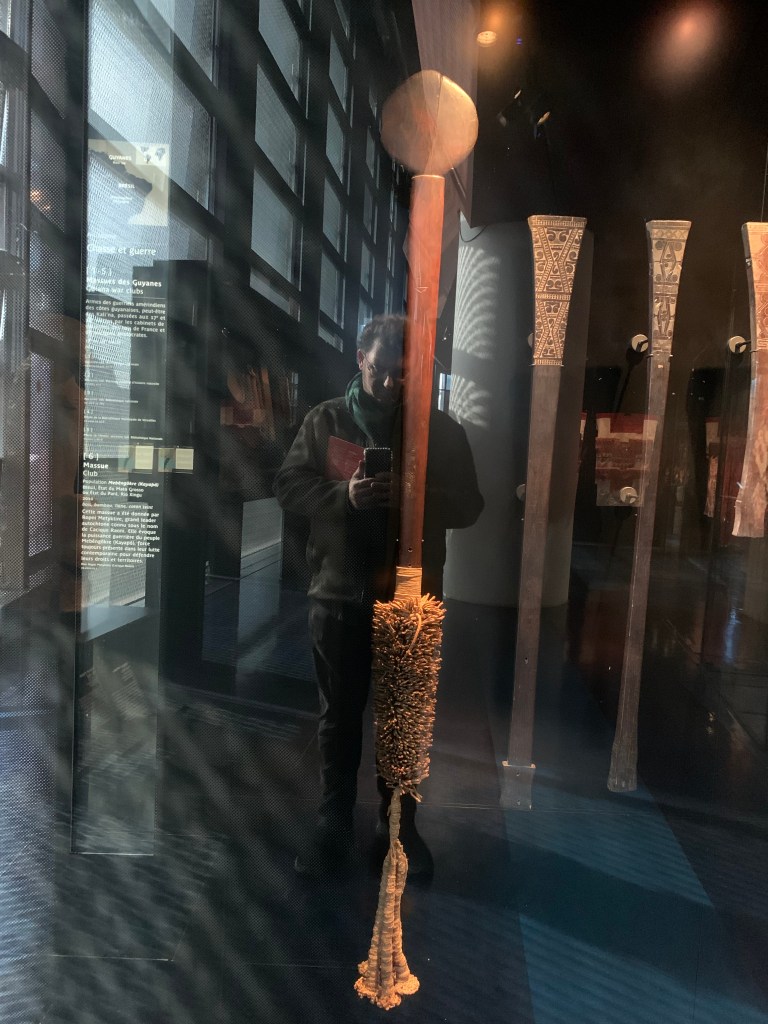

In 1580, the French humanistic philosopher Michel de Montaigne, the first great essayist, published in his first volume of Essays one such document titled “Des cannibales,” or in English “On the Cannibals.” In it, Montaigne spoke about a Tupinambá man from Brazil who he met in Rouen, the great port in Normandy where most of France’s trade with Brazil was based. Montaigne described how the Tupinambá became famous in his time for their cannibalism, rituals which were an intrinsic part of their culture that made them seem alien to his own, and dreadful in their otherworldliness.

Yet Montaigne saw also in the Tupinambá something of a reflection of his own world. 1580 saw France embroiled in the Wars of Religion, which lasted nearly 40 years and cost the French people a great many lives across several generations. Montaigne retired from public life in the civil service in part out of disgust for how the course of French history had gone, disgust that Frenchmen were not just killing fellow Frenchmen but torturing them and bringing ruin onto their families and communities all in the name of religion.

Religion is a tricky thing in human cultures. Most religions today are intended to give their believers a guide to living a good and true life; the greatest commandment which Jesus offers in the Gospels is to “love the Lord, your God, with all your heart, with all your being, with all your strength, and with all your mind, and your neighbor as yourself.” (Luke 10:27, NAB) I’m a practicing Roman Catholic, as a priest once said to me “I’m practicing, I’m still learning how to do it right,” and at the end of the day the best any of us can do is try to be good people, to make something positive and impactful of our lives, even if it is only a small impact on our immediate friends and families. I am religious for many reasons which perhaps someday I will write about here.

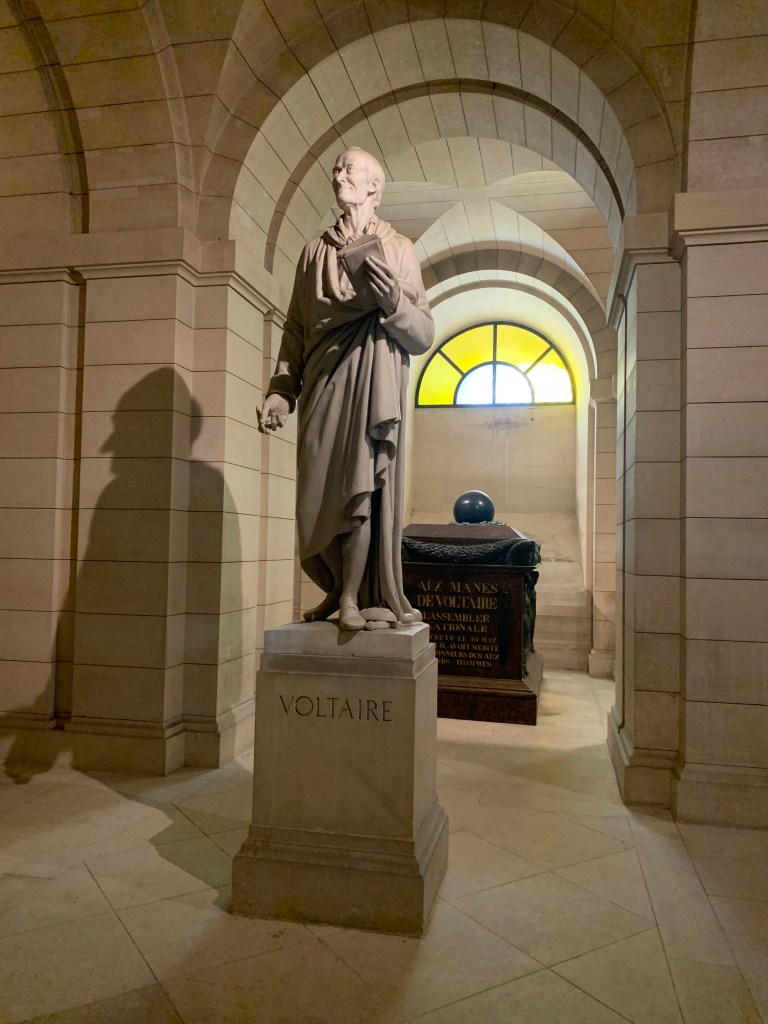

Yet I am also a skeptic, much like Montaigne whose essays reflect this uncertainty about life, humanity, and established norms. Montaigne’s skepticism reflected the empiricism that was born in the following decades of the Scientific Revolution and flowered 150 years later during the earliest stirrings of the Enlightenment as much as it came from the humanism of his own time during the Renaissance. Montaigne challenged his readers, his fellow Frenchmen amid their own bloodletting, to save their cries of barbarity for the Tupinambá lest they also “call that barbarism which is not common to them” at the same time. Montaigne thought it more barbarous to “eat men alive than feed upon them when dead.” The way in which this war is being prosecuted by Hamas, while they hold clear grievances, loses any sense of moral justice when, as Montaigne charged his countrymen, they “mangle by tortures and torments a body full of lively sense, wresting him in pieces.” The horrors of this war then, in all their wanton cruelty, show this twisted version of the human character in its fullest expression.

When I thought more about the war after it began last week, and as I thought of what I could write about it, about the renewal of this long simmering conflict in lands thought to be holy by three of our species’s largest religions, I was drawn to Montaigne’s words again, especially after reading reports from a journalist friend about the killings of infants and children by Hamas still defenseless in the earliest verses of their song.

What worries me is this idea of religious war, fighting “under pretense of piety and religion” in Montaigne’s words, remains in my own Catholicism. I know there are some who adopt the image and iconography of the Crusaders of old to battle against what they see as the wickedness and snares of evil, desecrations against what they hold most dear. Theirs is a faith limited to only a few, a scarce number that will surely only grow within their own families. When one says, to quote Handel’s Messiah “if God be for us, who can be against us?” it is very hard to argue, let alone change the mind of those who see God on their side. That is a faith limited to only the most elect, denying the promises of salvation to “our neighbors and fellow citizens” who instead receive scorn at the least, torture, death, and dismemberment at the worst.

I worry about how large this war will become. It is not like the other sudden conflicts that Israel has found itself in throughout its young history as a modern nation-state. This is a war fought against a terrorist organization with clear backing from another power in the region. Will that power leave the shadows or be attacked directly by Israel to stop the flow of weapons and funds that at time of writing is likely going to Hamas? And if so, how far will the Israeli Defence Force go to defeat Hamas before they lose their own moral standing? This is why I do not care for the idea of just war; taken too far with too much emotion driving one’s judgement a just war can quickly become unjust and the warriors fighting in the defense of their own kind could resort to brutality like their foes “that exceeds them in all kinds of barbarism.” So, in the last week when I’ve been at Mass, when I’ve led my classes at my Catholic school in prayer, my thoughts have been on the victims of this war, the fighters who see their actions as their best and only recourse, and on the faint glimmer of hope that peace will someday return to the Israeli and Palestinian peoples. In an age when terror is as potent a weapon as any other, I hope those able to see an end to this war will find a way to start talking with each other again. Until then, just as Montaigne wrote 443 years ago, so too today we find ourselves “not sorry we note the barbarous horror of such an action, but grieved, that prying so narrowly into their faults, we are so blinded in our own.”

The translation of Montaigne’s Essays used here is based off of John Florio’s 1603 first English edition of the Essayes, or Morall, Politike, and Militaire Discourses of Lord Michell de Montaigne published in London.