The Lotus-Eaters – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

Photo: Ziziphus lotus, © Juan Valentín CC BY-NC 4.0 https://www.inaturalist.org/photos/427040191. No modifications made. Available under public license.

This week, comparing the benefits of pleasure with the rewards of good work.

A recurring challenge of my life is finding a good work-life balance. Perhaps central to this conundrum is the fact that I simply enjoy the work that I do, so I’m more willing to approach something work-related at all hours because it brings me joy. There are plenty of things that I need to do with my time, and plenty more that I know I will someday accomplish, yet I feel less pressed to push through any weariness or writer’s block to finish a given project today than I have in the past. For most things, I have a wide enough gap leading up to project deadlines that I can afford to work as I will on a given project. This is a luxury of the moment, which was foreign to me even a year ago, and I know well that the ample time I have now is a singular moment in my life that will likely not repeat often again. So, as long as I have the time to spend working on the Wednesday Blog and the handful of articles and book chapters that I’m writing, I’ll use that time to the best of my ability.

Each of us operates within the structures of our civilization, and within the cultural edifices built up over millennia that define our very identities. No one exists in true solitude everyone comes from somewhere. There are plenty of stories of loosening the burdens of life for the splendid abandon. Life is hard for all of us; one of the great unifying factors of the human experience is struggle. I doubt that either the richest or the poorest people alive today are fully happy and content in their present state. There are certainly things I would like to change about my life, things that I’m now approaching with the same resolve that I dedicate to my work and I see that among my family and friends too, such potent dedication to completing tasks difficult and easy alike that when all is said and done the doer can rest proud of their work.

Still, there is value to taking time to rest. I’ve developed a bad habit of sitting at my desk until I’m so tired that I can’t sit up straight, or even to the point that I find one eye closing so that I can keep reading with the other. These make for good stories but they’re bad habits overall. It seems to me like there’s so much to learn and not enough time to commit it all. We Americans are particularly bad at our work-life balance. While we have a strong work ethic in this country, we don’t give ourselves enough time to enjoy the fruits of our labor. I now work at some of the places where otherwise I would go to rest, places like the Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts where when I returned to Kansas City in December 2022, I was a frequent patron of the Kansas City Symphony’s performances until March 2023 when I signed on as a Team Captain of the Volunteer Usher Corps. Now, I work at the Kauffman Center and while I don’t get to relax and soak in the music there anymore, I’m proud of the work that I do and I work with people who I genuinely enjoy being around. In fact, working at the Kauffman Center has magnified the value of my historical research and writing even more. That’s what I love most in all the things that I do because it’s what I’m best at, and it’s through academia that I’ve met some of the people I most admire in all the world. The last two months then when I singularly devoted my attention to researching, writing, and editing a new and better introduction to my dissertation I poured all my effort and energy into the task and the work shows it. Yet I also drained myself of that same strength and realized that the working hours I kept four years ago when I was reading 12 hours a day in preparation for my comprehensive exams were no longer tenable. Life moves on, and with the changes in my life so too my stamina for these sorts of long hours have changed. I’m doing a lot more now than I was during the height of the pandemic in January, February, and March of 2021. Thus, it’s reasonable to say that I cannot do quite as much of the same things that I once did.

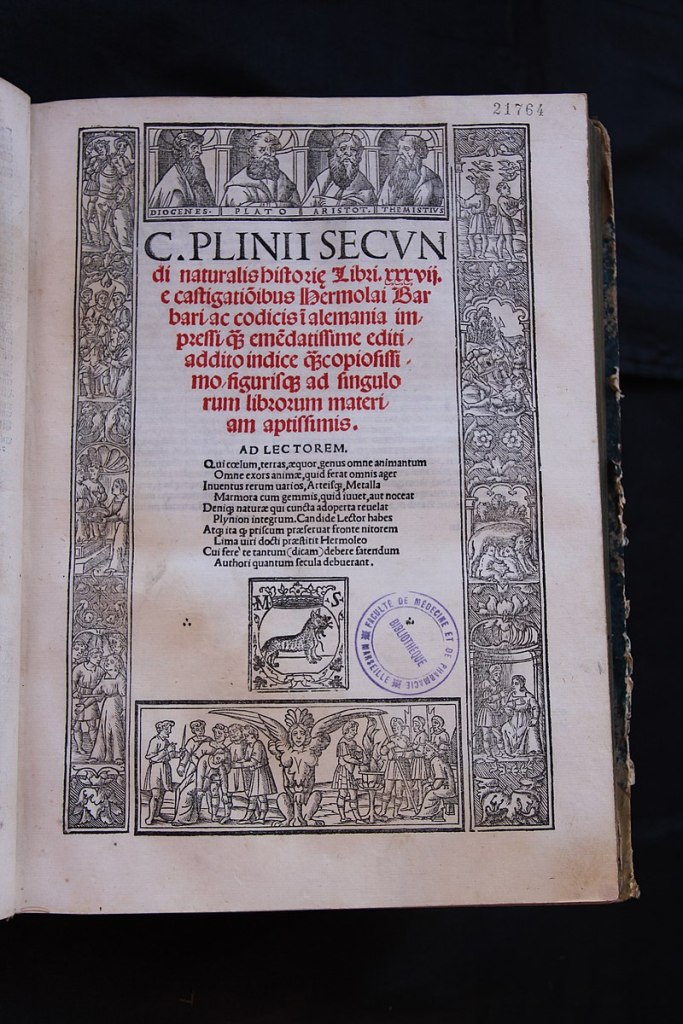

There are times when I can get so caught up in what it is I’m doing in the moment that I miss the world going by. I mourn a little bit how fast 2025 has been for me, there are things I wish I had done in the first half of this year that I failed to do for one reason or another. Often those reasons were out of my control. Yet they remain monuments to things that could have been. In other cases, though those things are goals which I turned away after finding better things to pursue. I’ve learned that I must remain open to change, flexible in my ways of living and doing things. How many times have I thought I was done with my dissertation only to be told that there was still more work to do? I know that endeavor defines my career and will continue to do so as long as I’m contributing to the scholarship of Renaissance natural history. Still, at times the idea of abandoning my efforts and falling into a state of rest has its appeal. At this moment, I would appreciate a vacation, even if only 24 hours away from my work. I took some time to enjoy the friendly company of my brother Hibernians and their families, and my Gaelgeoir friends this weekend at the Kansas City Irish Fest. It was lovely using that time to be with people whose company I enjoy, yet it was just as great a joy to return to my work this week and especially now that I’ve finished this round of work on my dissertation’s introduction to return to editing my translation of André Thevet’s 1557 book Les Singularitez de la France Antarctique. I had a delightful day spent reading through the Loeb Classical Library and the Perseus database hunting down Thevet’s Greek and Roman references on the geography, ethnography, and zoology of Sub-Saharan Africa.

The legacy of those ancient authors lies heavy on the European perception of their southern neighbors. The Greeks especially perceived Libya, their name for Africa, as the great desert landmass on the southern edge of their world. Thevet wrote that Libya was named by the Greeks for the southwestern wind, or Lips (Λίψ), a notion he got from Aristotle’s book the Situations and Names of Winds.[1] Thus, while Libya was the Greek name for Africa as a whole in antiquity, that the name was associated more with the southwest than the south suggests that their notion of Libya was west of Egypt and in the general vicinity today known as Libya. Further west along the Mediterranean coast of Africa lay an island where Homer records that Odysseus’s ship made a beachhead born by the north wind across what Robert Fagles translates as “the fish-infested sea.” On the tenth day “our squadron reached the land of the Lotus-eaters,” who Homer described as “people who eat the lotus, mellow fruit and flower.” Odysseus’s crewmen “snatched a meal by the swift ships” and found as “they mingled among the natives” that they “lost all desire” to do their duties

“much less return

their only wish to linger there with the Lotus-eaters,

grazing on lotus, all memory of the journey home

dissolved forever.”[2]

The lotus-eaters of the Odyssey who live in bliss induced by the plant. Their worries carried far away they could bask in the glow of their sun and live out their days in a sense of peace. Yet Odysseus saw in this idyll a great distraction from what must be done, he and his crew needed to still return home to Ithaca. The king in his wisdom continued his story,

“But I brought them back, back

To the hollow ships, and streaming tears––I forced them,

Hauled them under the rowing benches, lashed them fast

And shouted out commands to my other, steady comrades:

‘Quick, no time to lose, embark in the racing ships!’––

So none could eat the lotus, forget the voyage home.”[3] (9.92-117)

The danger lay less in an immediate threat to life and limb but rather in a threat to mission, to vocation. Odysseus knew his charge was to shepherd as many of his men home as he could; what a tragedy it was that after all his efforts he returned home alone. The threat of the lotus-eaters lay in their carefree abandon of the need of self-preservation. Eventually, had the King of Ithaca and his men stayed on the island they would have faded in body and in spirit, dying not in war but by becoming stale and wasting away slowly until they had not even their memory to keep alive. Too much of a good thing becomes a bad thing, just as everything changes over the long dance of time.

Moderation then is the best way of living, to do things such that we humans not only survive but thrive in the conditions in which we find ourselves. Aristotle expresses this best in his Nicomachean Ethics that for every sort of action or feeling there is an excess and a deficiency and between them a mean which is the moral virtue. Thus, the lotus-eaters lived in a state of self-indulgent excess, born from their love of the lotus plant and the way it can make all their troubles disappear.[4] Aristotle argued that “temperance and profligacy are concerned with those pleasures which man shares with the lower animals, and which consequently appear slavish and bestial.”[5] It is human to have passions, desires, and urges to do one thing over another, yet it is an entirely different thing to give into those passions and abandon control over one’s own life. I think it is a greater sorrow to give up this control thoughtlessly than it is to have that control taken from you, even if the act of subjugation remains in the eye of the subduer and only as powerful as society wills it to be. This is something we too often forget: so many of the bad things that go on in our world are things of our own making. We choose to allow rampant gun violence in our country, or to let the institutions of our democracy crumble, or to let people go hungry, die from treatable diseases, and remain illiterate all because people in positions of power benefit from having others in need. I suspect that we don’t have to live like this. Perhaps the root of these societal woes comes from an understandable inability to understand death, that final act of life which often is so very unfair to the dying and those left behind. So long as the greatest inequity exists then why should we bother with trying to fix our own problems?Dear reader, I’ve been writing this Wednesday Blog now for four and a half years, and I’ve always said that my one rule for this publication is that I will end it once it’s no longer fun to write. Just before the pandemic during a family gathering, one of my uncles remarked that he had no interest in retiring soon because he loves the work he does. This struck me because it explains why I’ve stuck around in academia in spite of all the trouble I’ve been through in these past few years. I do this work because I love it; I write because I enjoy writing, and I’m writing to you today to suggest that we could make our world a better place to live for ourselves and our children and grandchildren who’ll come after us, we just have to leave the island and its lotuses and climb back into our boat and set out onto the fish-infested sea again. For all that I’ve learned about a great many topics, I still often need reminding to do basic things like stop reading or writing late at night and go to bed. I suspect that’s the case for most of us, that we get caught up in the worries or passions of the day and lose sight of the good things that we can do to really find true peace. Here in the United States the first big step that we ought to take is reconsider how we prioritize work to such a degree that it becomes life itself. We ought to work to live, not live to work. On this Labor Day week that’s as good a starting place as any.

[1] André Thevet, Les Singularitez de la France Antarctique, (Antwerp, 1558), 4v ; Aristotle, Situations and Names of Winds 973b, 12–13.

[2] Homer, Odyssey 9.106–110, trans. Robert Fagles, (Penguin, 1996), 214.

[3] Homer, Odyssey 9.110–117, trans. Fagles, 214.

[4] Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics 1118a.

[5] Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics 1118a, 8.