New Worlds – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

This week, I reflect on the flexibility of the word world.

In my field the focus is often on nomenclature as much as it is on the history itself. We, early modern historians of the Atlantic are left dealing with the original intent of our historical subjects while also reckoning with the legacies of their choices in the living world today. That word world is one such central question, after all what does it really mean? In a twenty-first century context the world is synonymous with the Earth itself. I see in the sixteenth century the creation of the current state when the world can be a planetary designation. For past generations the world was something smaller, at most hemispheric yet more often regional in character. André Thevet’s use of the French word sauvage to define the alterity of those beyond his own world in turn set boundaries about his own world, what he wrote about was a Christian world centered on the Mediterranean that was a natural outgrowth of the classical civilizations of Greece and Rome.

I am hesitant then to use the term New World in my dissertation. Sure, it was a term in use in the sixteenth century, popularized by Peter Martyr d’Anghiera (1457–1526), yet in our time it’s gained enough shackles from the dark legacies of the conquest and colonization of these continents that I want to be conscious of my twenty-first century readers even as I seek to place my historical narrative in the sixteenth century. Thus, I argue instead that this new world was created by the conquest and colonization, that it is a new global world born from the encounter between the many old worlds that came before. This follows the arguments made by Marcy Norton concerning a Mesoamerican classical past to which the Spanish in particular looked when placing their new administration upon the remains of the old over the indigenous societies in present day Mexico.[1] I see in how Thevet described the one part of the Americas that was fully colonized in 1556, namely the island of Hispaniola, a new world in all its novelty and experimentation.

I grew up knowing of the Americas as the New World, it’s one term I remember hearing very early on in my youth. Even then, I felt a sense of reluctance at it, after all new things aren’t necessarily all good, so does that mean our New World is in fact worse off than the Old? Most of my family only arrived in the United States in the last four to five generations, at the time within the last century, and so for us America was still in some ways new. I treasure the stories my dad told me as a young boy about Chicago, where we lived; those stories were likely my introduction to history that led slowly toward the career I’ve now chosen. Even now, if I’m looking for something fun to read it will often be something about my hometown as it was a century ago. In 2024 I spent many happy hours engrossed in Jay Kirk’s biography of Carl Akeley (1864–1926), and a few months later once it was released I read eagerly Paul Brinkman’s Now is the Time to Collect about the Field Museum’s 1896 expedition to Africa. Granted, both deal with the same subject, the museum where my own curiosity was first sparked as a young kid, yet they are mementos of that same nostalgia that draws me back into what I thought of when first I considered this term New World. It speaks to Churchill’s famous final rousing word of hope in his “We shall fight on the beaches” speech that Britain need hold out “until in God’s good time, the New World, with all its power and might, steps forth to the rescue and liberation of the Old.”[2] This dichotomy between the youthful New World and our older cousins across the water is echoed in Bernard-Henri Lévy’s 2018 book The Empire and the Five Kings about the decline of American geopolitical power in the present century. Lévy wrote of America, the Empire, as the sons of Aeneas who several generations ago returned east to the Old World to liberate it as Churchill hoped. Yet now, the imperial sons of Aeneas are themselves fattened by their spoils of victory and incapable of meeting the struggles of the current moment as the threats are multiple and not focused on one rival superpower as they were for much of the last century.

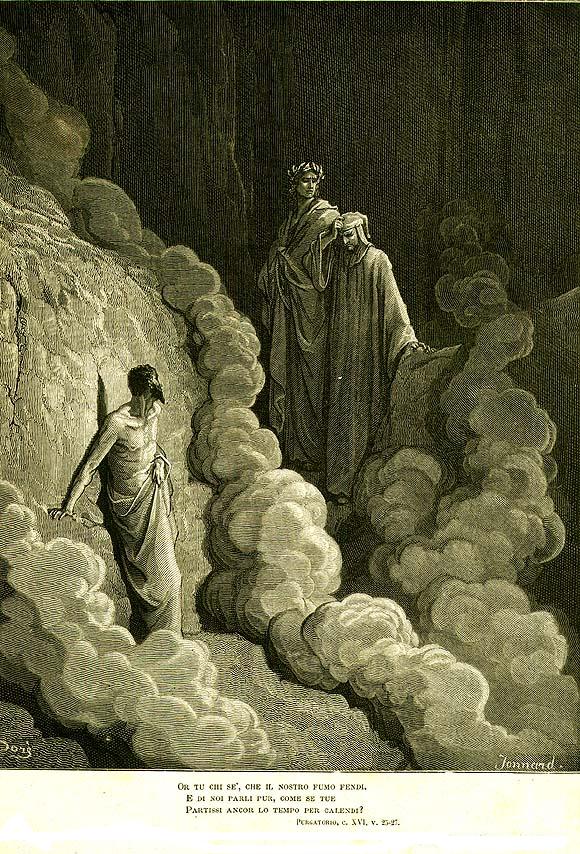

Perhaps this is the key facet of this whole conundrum now: not only is the world so diffuse as to merit multiple definitions, but it reflects the uneasy global world in which we all live. For me the disquiet in all this comes just as much from the fact that the benefits which our interconnectedness ought to have brought––peace, economic, political, and social prosperity, greater human solidarity––are still mired in the same old problems of greed, small mindedness, and war as ever. We live in the shadow of Cain as much as in the warm glow of that optimism which keeps the home fires burning. We are at a place in our development as a species where disease, hunger, poverty, and war could all be avoided or cured on the sociopolitical level. We merely lack the will to do any of that. The optimistic promise of this New World which I perceived as a kid in Chicago remains but one vision of our shared reality. The New World into which I was born is built on the remnants of those old worlds that were often assimilated with violent force.I like to find the positive, if possible. When I was considering what I wanted to pursue in my doctoral studies I looked at what my friends were doing and first decided that I didn’t want to do something that would be depressing or sad. I wanted instead to focus on something that would fuel my curiosity and that connected back to those things which I’ve been most interested in throughout my life. I chose to study André Thevet’s sloth because the idea of being a sloth historian made me laugh. Now, with my first peer-reviewed article on the subject published with the journal Terrae Incognitae I feel that the work of these last six years is finally paying off.[3] That work considers the creation of a New World, while balancing contemporary sentiments around that term with historical perceptions of the same. I am after all someone who studies the past for the benefit of illuminating something as of yet uncovered about my subject. That said, I’m writing for readers living now and, in the future, and need to bear their perspectives in mind. That’s at the core of any communication: we learn foreign languages in order to communicate with people from other cultures, countries, and even worlds. I know that my writing is tinged with my own idiolect, yet I hope it remains universal enough to be understood by anyone who is curious enough to read it.

[1] Marcy Norton, The Tame and the Wild: People and Animals After 1492, (Harvard University Press, 2024), 305-313.

[2] Hansard HC Deb 04 June 1940 vol 361 cc787-98.

[3] Seán Thomas Kane, “A Sloth in the First French Colony in the Americas,” Terrae Incognitae 57, no. 3 (2025): 1–15.