Politics and the Citizen – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

Words are at the center of all our political debates. They are at the center of our lives, the core of our existence. We would not exist as we do without words. Words have tremendous power to do good, to inspire people to achieve wonderous things, to rise above what they thought possible and make a better future. Yet words are also dangerous when poorly used. They can have the effect of destroying trust between people; they are capable of breaking up families and communities. Without common words we cannot have a common society.

I was struck last week reading in the New York Times how the protests following the recent Supreme Court ruling of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization were rephrased by the far right as an “Insurrection.” That is a word that has been far more justly levied at their own faction, whose actions on January 6th last year proved their lack of faith in a democratic society. Other words and ideas have been poisoned by the same fearmongers from Critical Race Theory to the Green New Deal. These are ideas and proposals that if considered in their true meaning have merit, yet any mention of them in the political square anymore will be met with the screaming banshees in the wings whose greatest weapon and sole power is the volume of their voices.

One such word which they have demonized by their own behavior, perhaps the most critical word to our democracy, is politics. It is taboo now to be political in a crowd when you don’t know everyone else’s own political views. A professional soccer team wearing practice shirts recognizing racial inequality is dangerously “politicizing” an otherwise family event. It’s curious to me because their own use of the word “political” has no bearing on the actual meaning of the word, nor on its origins.

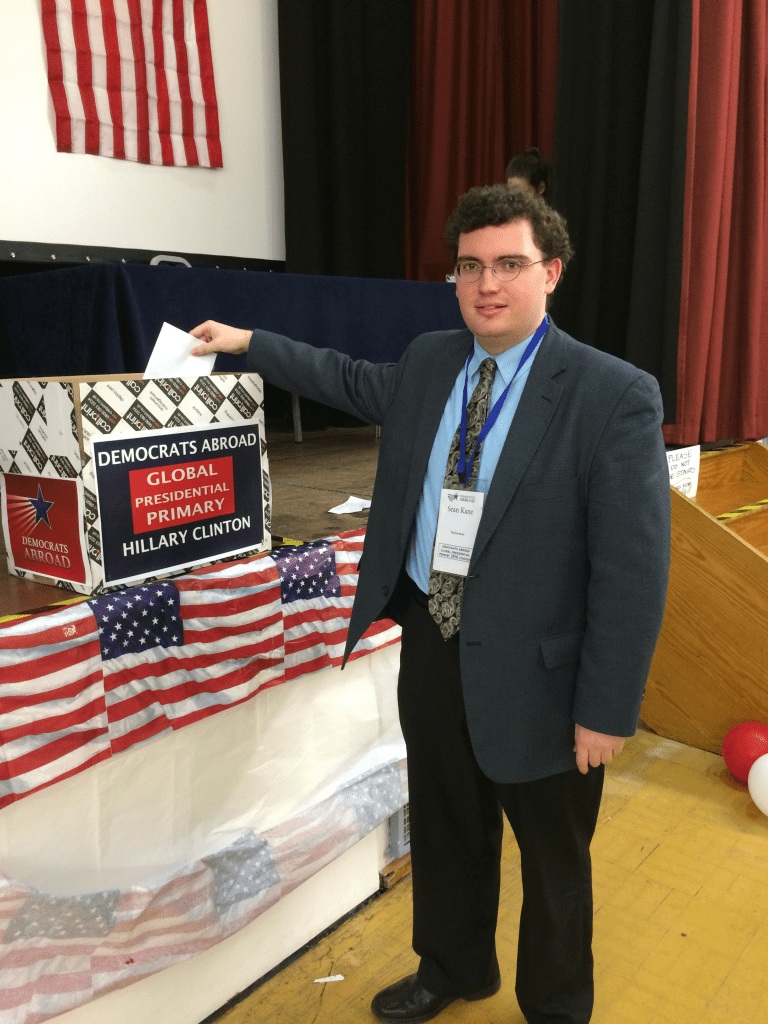

The word political simply refers to the idea of the city, the polis in Greek. To be political is to be a citizen, an active member of society. To be political is to participate in government through voting, running for public office, and serving the people in the public sector. To be called political is one of the greatest honors anyone can bestow, for it means you care about something greater than yourself, you care about your community and want to contribute to its future.

In the ancient and medieval context, a citizen was far more particular of a person than today. The idea of universal suffrage is a modern thing, something that has been fought for down the generations and even still is being fought over today. Today though I believe the best way to describe a citizen is simply a person who wants to contribute to their own community. They need not have the papers conferring official legal citizenship in their country of residence, for even without those individual people can make a difference to their communities.

This is intolerable to those who demonize the word political. Why else would they make such an effort to poison an entire population against such an idea that at its core is meant to better their lives? It is intolerable to them because they know their views, as extreme as they are, are in the minority among their fellow citizens. There are generations of Americans who have come to recognize the benefits of democracy, and who have pushed us to improve upon those benefits already existing, that they might be extended to more and more people until eventually some day we may have true political equity.

Yet now, as has happened in every generation since the founding of the first English colonies on the East Coast 415 years ago the powerful voice of a small few who see democracy as a threat to their own interests has influenced the course of affairs in this country to the great detriment not only of we the American people but of humanity at large. I’m speaking of course of the West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency ruling made on the last day of the recent session of the Supreme Court. In that ruling the conservative majority declared that regulation should only be conducted through legislation. This means the President and any federal agency acting under the authority of the Presidency, even if acting in the best interests of the people they are sworn under oath to serve, have less ability to create broad regulations that are not expressly allowed under Acts of Congress.

The voices of a few who feel greater concern for their profits than they do for the future health of humanity and our home planet spoke up and were heard over the cries of the rest of us. I could say let’s trust in Congress to do their part now and legislate new regulations that will replace what was stripped from those executive orders revoked by the Court but those in Congress with the power to save us are also listening to that swansong of the soloists rather than the Dies Irae being belted by we, the chorus.

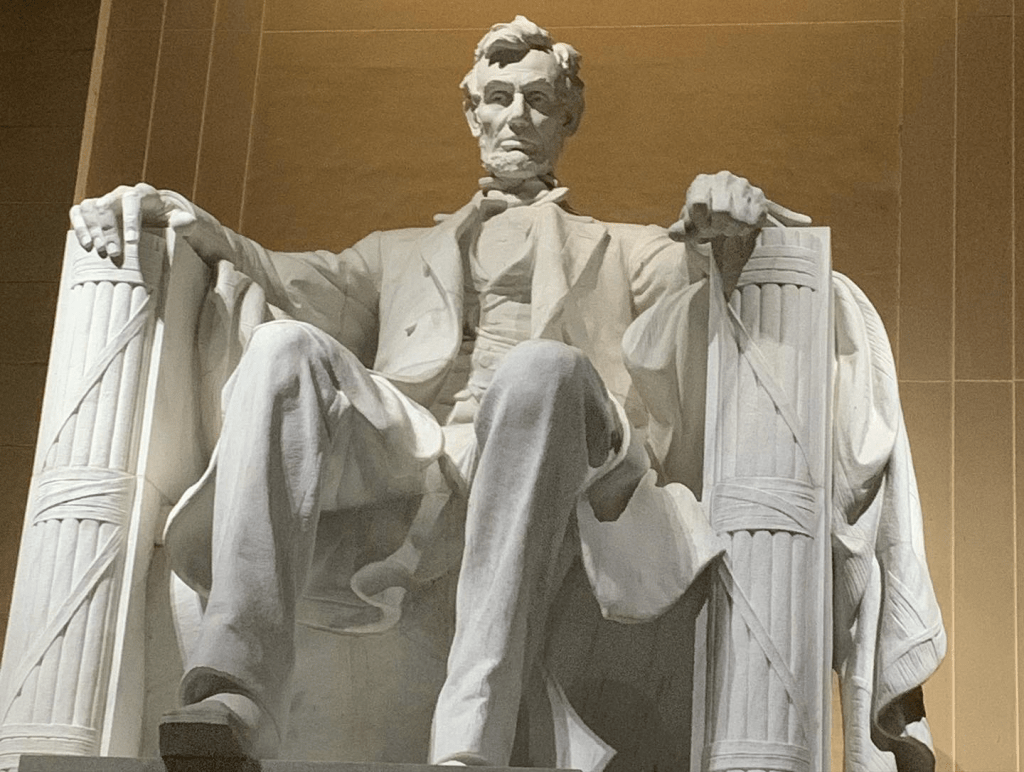

Our politics are in many ways broken by our extreme partisanship. It is this word, partisan that ought to be used when the far right uses the word political as a curse. We retreat into our slogans but don’t actually talk to one another. One side hears “Defund the Police” and the other “Law and Order” and neither leaves the table any better off. Rather, both parties find themselves far less willing to talk to the other, to find things in common with the other, to learn from each other. Once again, those fissures that threatened to make two countries out of one in that messy divorce of 160 years ago that left 6% of the population dead are beginning to show.

Do we really want to go down that path again? Do we really want to fall into such political disfunction that we cease to see each other as fellow citizens and instead as enemies? We have let the battle cry change from “E Pluribus Unum, Out of Many One” to “No Compromise”, leading us to rally ’round our own partisan flags to the detriment of our common threads. I want to cry out in pain every time I see the American flag used as a symbol by those who want to be exclusionary, by those who would see all it has stood for over these past centuries be replaced by the worst of our nature: by our greed.

As citizens of a democracy, we have a right to know, to understand, and to discuss these questions of who we were, who we are, and who we want to be. And, as citizens of a democracy, we do have the right to dissolve our democracy, to end the experiment that’s been running for so long. I recognize that our current federal system isn’t going to last forever, nothing does, yet I remain hopeful that when it does eventually take its leave that that system will be succeeded by something better, crafted by the wisdom and love of another set of founders inspired by the precedents set by the first, who will craft a new system with all the best traits of our own yet reimagined in such a way as to overcome the faults in our own today. Until then, we citizens are caretakers of this democracy. It’s a fragile gift passed down to us from our ancestors, which we get to treasure and improve as best we can so that when we pass it on to our descendants it will be in better shape than how we found it. Let’s do our duty.