Artificial Intelligence – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

Concerns have been raised lately over the risk that the increasing artificial intelligence of our computers poses to humanity. I think the risk truly lies in who teaches these computers and what they are taught.

There have been stories of humans striving for divine heights for millennia, whether it be Icarus flying too high as the wax of his wings melted in the Sun’s rays, or Dr. Frankenstein creating life from the remains of the dead only to find his creation a terror because it couldn’t find a home in human society. In more recent generations stories of cyborgs like Darth Vader, the Borg, and the Cybermen have shown the horrors that augmenting the human body with mechanical parts could bring, especially if those augmentations overwhelm the human.

Many of these risks bear resemblance to the countless stories in our history of people who were raised to fear rather than to love. Darth Vader is merely a tragic figure in a mask lacking most of his limbs without all the anger, hate, and rage that boiled inside that suit sinking the man deep within the façade of Vader so that his climb out, his redemption took the greatest of effort and over two decades to achieve. A central fear over artificial intelligence is in how narrow-minded computers traditionally tend to be. They are machines that run on binary code, 0s and 1s, which allow every one of their decisions to be narrowed down to an up or down choice. There’s little nuance in that, nuance that distinguishes the human from the machine.

In the last few years our machines have gotten far better at interpretation and understanding hints of nuance. What started as humorous easter eggs embedded into virtual assistants created by Apple, Amazon, Google, and Microsoft like answers to riddles or references to the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy have become the minute personalization of service provided by the newest generation of artificial intelligences, notably those developed by Microsoft’s Open AI, the creators of Chat GPT. I was unsurprised to see that Chat GPT could devise information for me regarding very particular subjects like André Thevet (1516–1590), the focus of my dissertation, or about the Ancient Order of Hibernians, the largest Irish Catholic fraternal order in the United States of which I am a member. Yet what struck me was the speed at which Chat GPT learned how to communicate and relay ideas. No longer was there a bias towards English and several other languages as has been the case with the other AI text generator Google Translate; Chat GPT was able to answer questions I asked it in Irish, and when I pressed on further in the Connacht dialect that I speak it replied in the same.

I am cautious about using artificial intelligence without due process or consideration of the ramifications. I want the things I write to be my own, without much bias from a computer beyond the fact that nearly everything I write today is typed on a computer rather than written by hand. This reminds me of how our very understanding of language is technologically influenced from the start. Without the technologies we and our ancestors developed over thousands of years our languages would exist orally, spoken and sung, heard, yet not read. The very word language comes from the Latin lingua, which has a very close sibling word dinguameaning tongue, not unlike how in English an older synonym for language is tongue itself. This distinction is pressing for me because much of the ancient history of my Irish Gaelic ancestors was only written down centuries after the fact, rendering those stories from the ancient epics prehistoric in the eyes of the historical method. I recognize their view: after all many of the characters in epics like the Táin Bó Cuailnge are thought to be personifications of ancient gods and goddesses, Queen Medb in particular. I still bristle a bit in frustration at hearing that, especially when an explanation I wrote of the anglicization of my family name from Ó Catháin to Kane was referred to as a “prehistory” by one fellow academic. Without the technology of the written word there is little precedent that we would find acceptable to distinguish one people’s history from another people waiving it off as mere prehistoric myth.

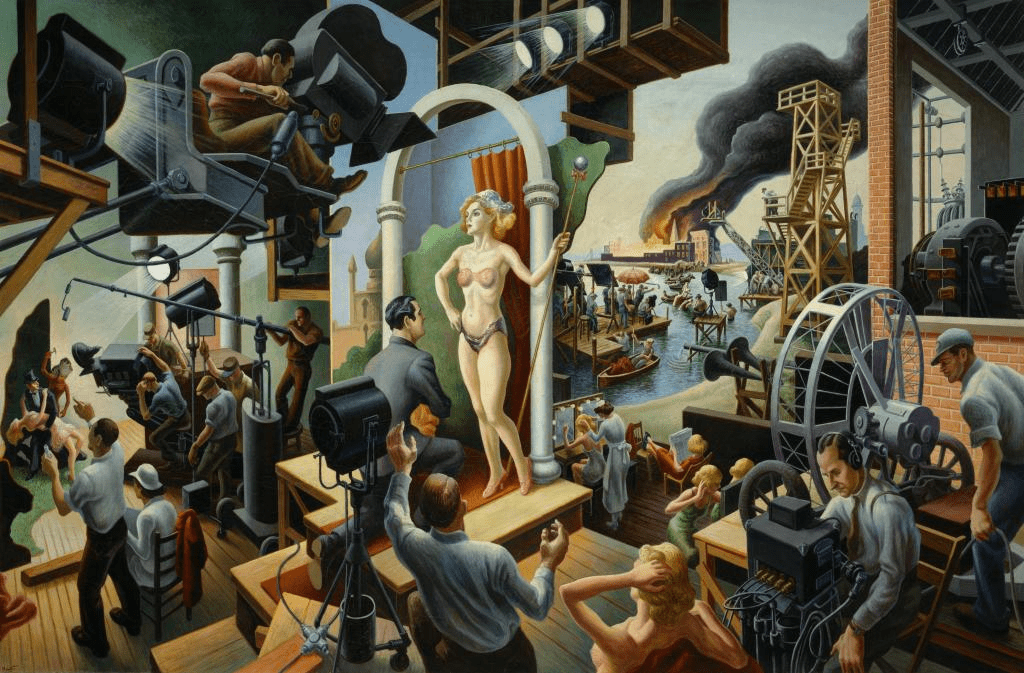

Still, artificial intelligence remains central to my life and work today from my ability to interface with the computer in my car vocally to the spell check that doesn’t care for the handful of Irish names in the previous paragraph telling me to rework those. Over the last three weeks readers of the Wednesday Blog will have seen a series of images that I created using Open AI’s image generator DALL-E 2. I once had more skill as a sketch artist, but have long since fallen out of practice, in part due to the discouragement of an art teacher years ago. So, rather than try to create all these images myself with paper, pencil, and watercolors I instead decided to see what an artificial intelligence could do. I asked DALL-E 2 to create images in the style of Claude Monet (1840–1926), the French impressionist painter whose works I deeply admire that depicted all of the main characters as well as several of the settings on Mars. Those images came to embody “Ghosts in the Wind” in a way that I’m quite pleased with.

The fears that many of the leaders in artificial intelligence have been speaking of lately reflect as much the potential that their creations hold as in the worry that our own long history poses. We have seen time and again as technologies are created and twisted for destructive purposes. This call for caution is very much warranted in that long lens, yet I think behind it is a concern that there are enough people or powers out there who would want to use artificial intelligence to further their own ends to the detriment of everyone else. Many of the beta canon explanations for the Borg lie in genetic experimentation with nanotechnology injected into organic tissue that overwhelms the organic and through a collective hive mind dreams up a desire to assimilate all other organic life. Whether we’re looking at that emerald tinted nightmare or at the vision of a computer that will only stop its program once it’s played all the way through, we need more safeguards against both the human inclination towards chaos that will continue to influence A.I., and against the resolute binary inclination towards order of the machines. As the moral of Fritz Lang’s 1927 film Metropolis––the first great science fiction film to ask about artificial intelligence––says: the mediator between the head and the hands must be the heart.