The North American Tour – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

This week, some words on the places I visited and the people I met on this North American Tour I finished on Sunday.

Earlier this year when I began to consider which conferences I would like to attend in Fall 2024, I knew from the start that my old stalwart of the Sixteenth Century Society would be top of the list. I was also interested in attending the History of Science Society’s conference for the first time after meeting a fair number of attendees from the 2023 meeting last year at my workshop in Brussels. Two conferences in two weeks is a fair amount of travel to undertake and money to spend. Yet there was more to be planned, for in midsummer I read a notice from the Society for the History of Discoveries about a special issue of their journal Terrae Incognitae about animals and exploration. I sent in a proposal which was accepted, leading to an outstanding offer to submit an article for the issue which I’m editing. So, knowing it would be good to meet the people of the SHD, I decided to submit a proposal to their conference as well.

If you’re keeping count, that means I went to three conferences in the last three weeks. I decided to call the series of talks my North American Conference Tour because this would take me not only to San Antonio but to Toronto and Mérida as well. I often thought about trying to do something like this where I visited two or three of the big continental countries in North America in short order; when I lived in Binghamton I fancied the idea of driving the 4 hours south to D.C. one day to sit in the gallery of the House of Representatives only to turn around soon after and drive back through Binghamton up Interstate 81 and across the St. Lawrence River to Ottawa to sit in the gallery of the Canadian House of Commons later that week. That never happened, in part because of the pandemic, yet I’ve undertaken similar trips in Europe on many an occasion so why would it be any more challenging here in North America?

The greatest challenge in this tour was that unlike stopping in Brussels, London, and Paris on a big European tour, I would need to fly between each of these cities and Kansas City in order to be where I needed to be in a prompt manner. I was excited by the prospect that all three of these cities could be reached in one way or another by direct flights from Kansas City. In the case of Mérida, the capital of Mexico’s Yucatan state, I would need to fly into Cancún and take the recently opened Tren Maya four hours east to Mérida to use that direct flight on Southwest. As it turned out though, I only had one direct flight throughout the entire tour. Southwest offers direct flights between Kansas City and San Antonio every other day, and they don’t fly that route on Wednesdays, so instead I flew to San Antonio with a couple hour connection at Lambert Field in St. Louis. Air Canada’s daily nonstop Toronto to Kansas City service only runs in a seasonal pattern and the season for that route ended 1 week before I was due to fly to the capital of Ontario, resulting in me having connections at the start and end of the trip in my original hometown at Chicago O’Hare. Then there was Mérida. I did seriously consider flying into Cancún rather than Mérida proper for the benefit of the direct flight. Yet the benefit of flying into Mérida itself and the still limited Tren Maya schedule meant I would still have to stay overnight in Cancún before flying home. So, I booked flights on United to Mérida through Houston Bush Airport which included an 8 hour layover on the way out and an 11 hour layover on the way home. I figured I could take advantage of the time in Houston in some way or another.

San Antonio

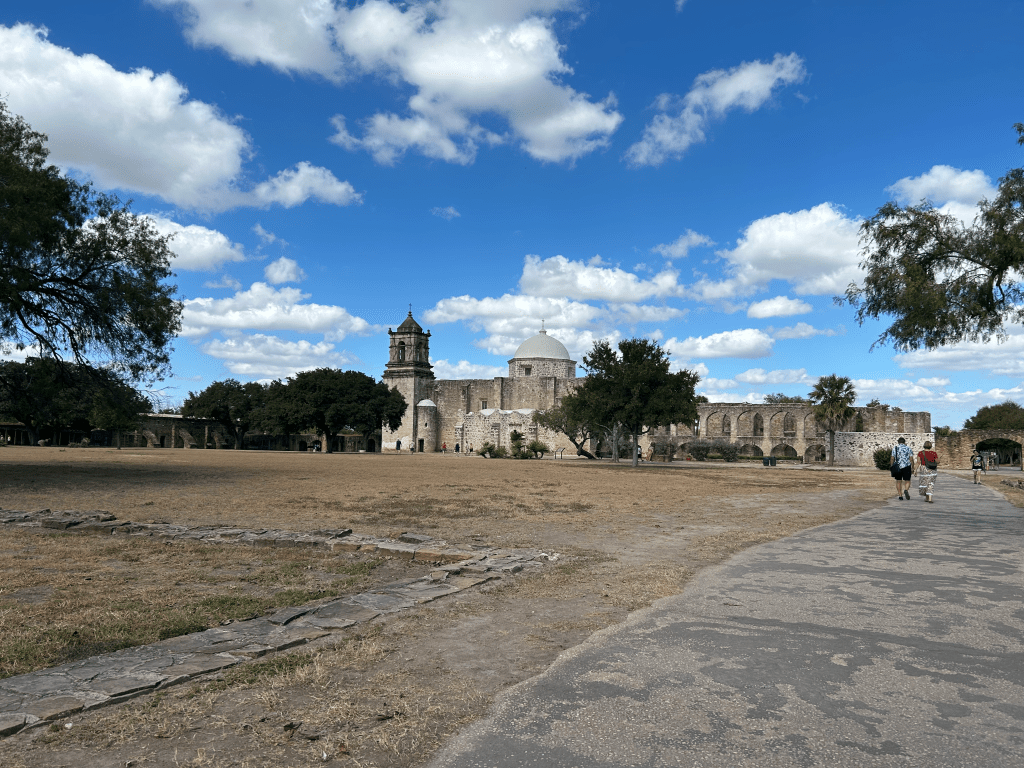

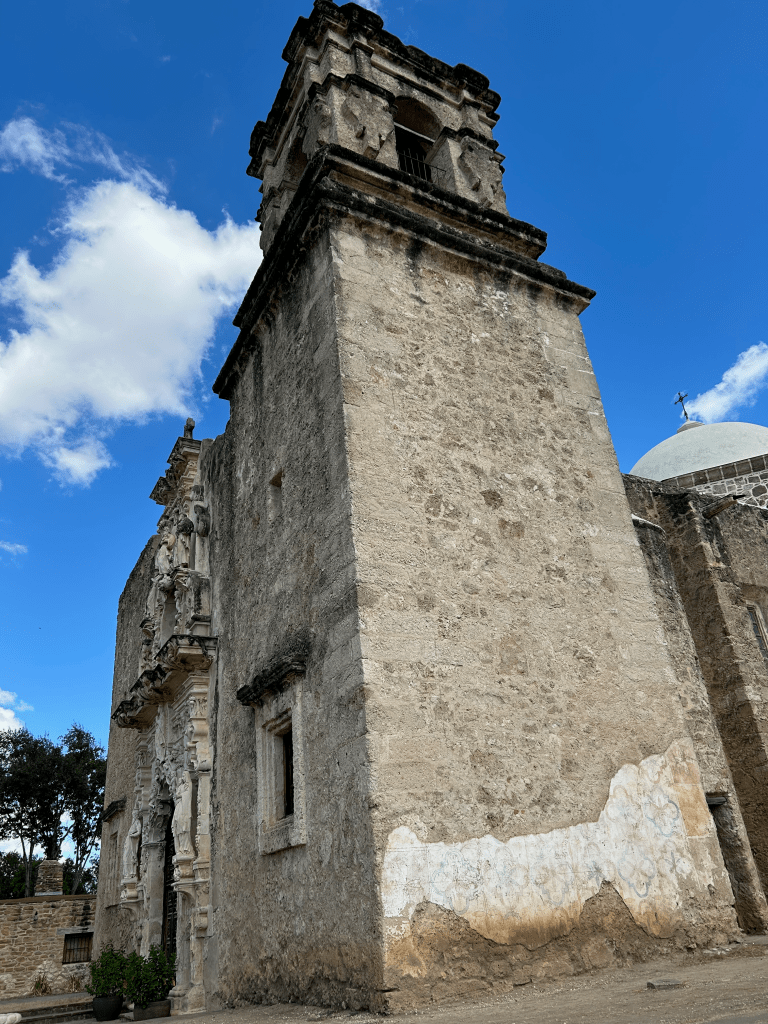

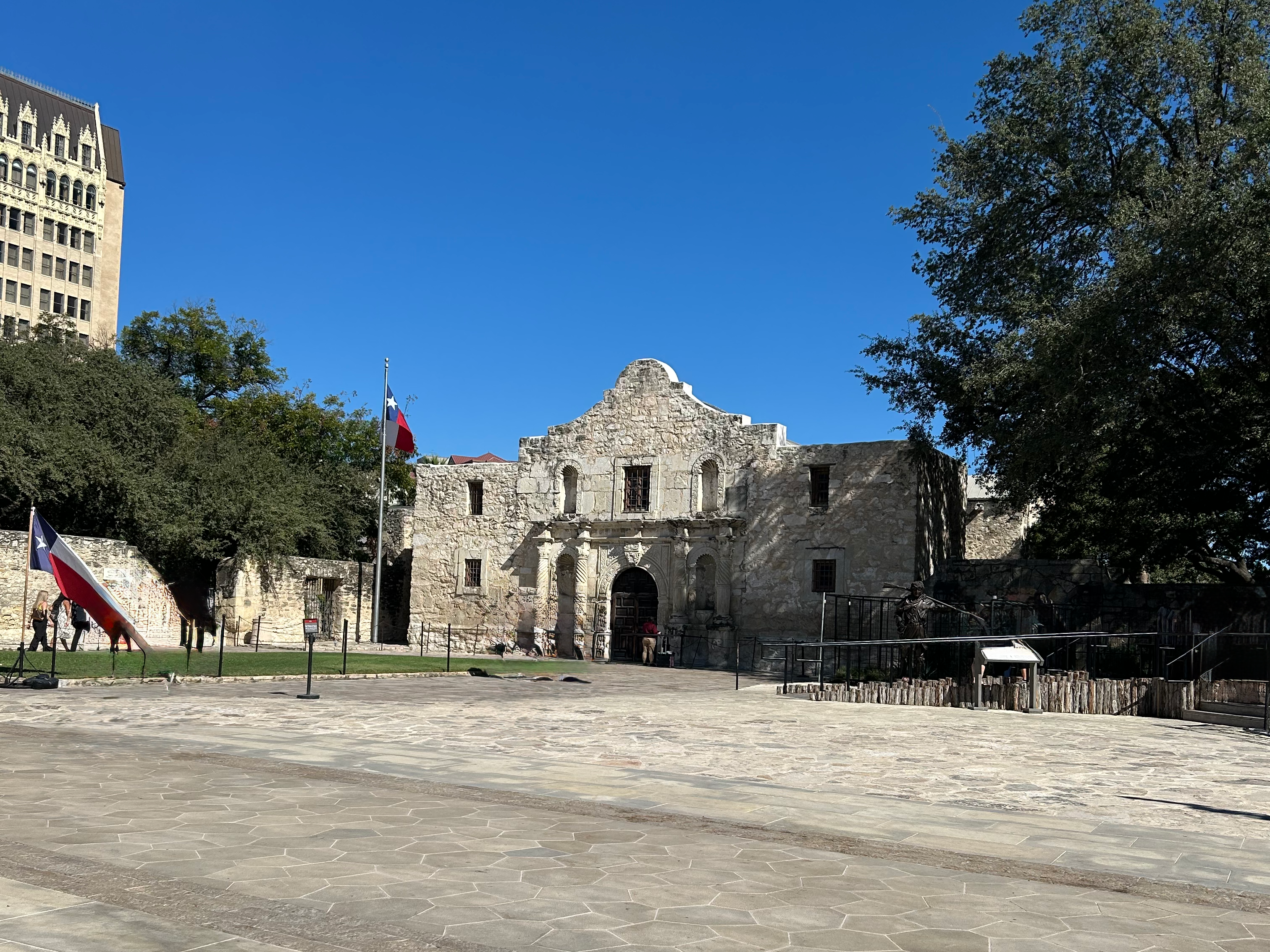

I traveled to San Antonio with my Mom, who jumped at the opportunity to spend a few days in that city. I’d only ever spent a few hours there about a decade ago when we were in Austin at my Mom’s office over her birthday weekend in May 2015. That visit to the Alamo City was cut short though by heavy rains and flooding. On this instance though, I fell in love with San Antonio. It often reminded me of the best parts of San Diego, another near-border city, yet it still felt closer to home both geographically and in its approachability. Before joining in the conference there at the Menger Hotel, we took a tour of the old Spanish missions south of downtown along the San Antonio River.

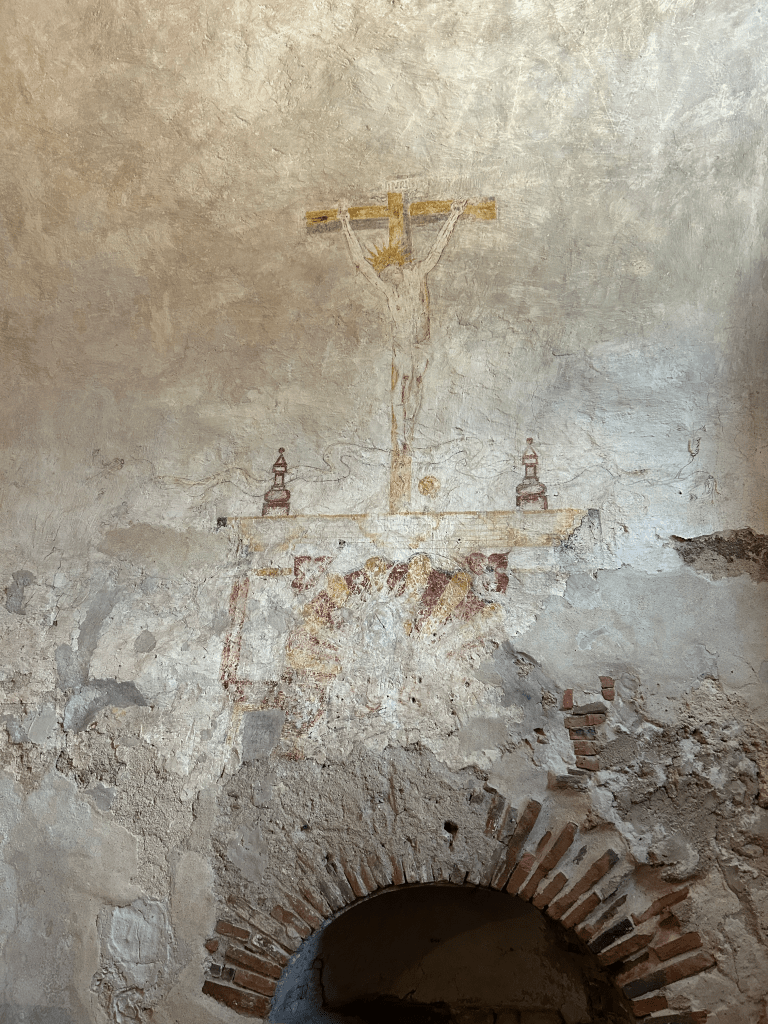

These four: Missions Concepción, San José, San Juan Capistrano, and San Francisco de la Espada brought the deep colonial history of this part of South Texas into focus. The tour guide explained that the Spanish decided to establish missions in Texas starting in 1715 in order to block French expansion from their new colony of Louisiane to the east along the Mississippi River. This was a full 200 years after the first Spanish conquistadores ventured north into Texas from their Viceroyalty of New Spain centered around Mexico City. The Franciscan missionaries who were sent north in the eighteenth century came from the Mexican city of Querétaro, some 740 miles (1,191 km) south by foot. Along with them came groups of colonists from the Canary Islands who were sent to establish a Hispanic presence around these missions alongside the majority indigenous population. The story of the Spanish colonization of Texas is a mixed one of both the story of the creation of a new ethnicity in the Tejanos, descendants of the Canarians and other Spanish colonists and the indigenous Texans including the Coahuiltecans, Payaya, and Pastia. Yet the other side of this story is the forced assimilation of these indigenous peoples to a new colonial way of life centered on the missions and their Catholic faith.

There is one more point I want to raise about the sudden Spanish urge to establish missions in Texas after 1715. This sudden colonial interest in Texas began after the War of Spanish Succession which was waged between 1701 and 1714 after the death of the last Habsburg monarch over the Spanish Empire, Charles II. Charles named Philip of Anjou, a grandson of Louis XIV of France as his heir, with Louis intending on having Philip succeed him as King of France as well, and uniting the French and Spanish Empires in a personal union. This terrified the Austrian Habsburgs, the Dutch Republic, and England & Scotland which in 1707 would unite to become the Kingdom of Great Britain. These opponents of the Bourbon succession of Philip of Anjou called themselves the Grand Alliance, and eventually won the war which was one of the first European wars to be fought in the Americas as well. In the peace that followed with the Peace of Utrecht, concluded by 1715, allowed Philip to keep the Spanish throne as King Philip V yet he had to renounce his claim to the French throne to ensure France and Spain would not unite in any fashion. Since 1715 then, the House of Bourbon-Anjou have held the title of King of Spain, in the process also unifying the older Crowns of Castile and Aragon save for several interregna during the Napoleonic invasion between 1808 and 1813, the First Spanish Republic of 1873-1874, the Second Spanish Republic of 1931–1939, and the Franco Regime which ruled from 1936 –1975.

With all this in mind if in 1715 France and Spain were newly ruled by members of the same family, why would it be as imperative for the Spanish to block the French from expanding further to the southwest out of the Mississippi Basin and into Texas? My suspicion may be that this intention was driven more by the fears of the viceregal officials in Mexico City than their royal counterparts in Madrid. Any of my eighteenth-century Latin American historian readers who may know the answer are invited to write in.

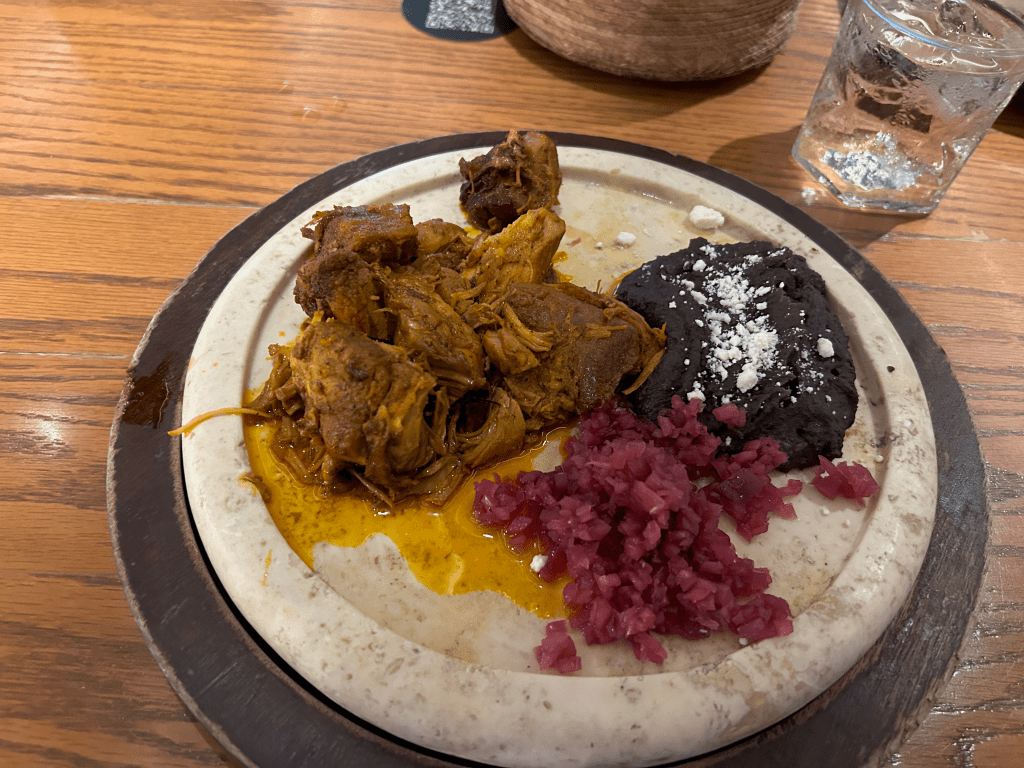

One of the finer parts of San Antonio is its river walk, which stretches along both banks of the San Antonio River through downtown and continues beyond the urban core as a series of foot and bike paths. We consistently saw mile markers for the river walk along our tour of the missions to the south of the urban core. Most evenings we walked from our hotel to the river and had dinner at one of the many restaurants that line its banks. My favorite of these meals were the enchiladas I had at the Original Mexican Restaurant, which was as touristy as it could get, I even paid a mariachi band to serenade my Mom with a song while we ate, yet it was still a delight.

We stayed at the Menger Hotel, an old historic edifice of San Antonio that was built by William and Mary Menger, a pair of German immigrants who arrived in San Antonio in 1847, just three years after the Republic of Texas was annexed into the United States. They opened the hotel in 1859 hoping it would increase business for the family’s brewery. The hotel is located on Alamo Plaza next to the old Alamo mission, originally named the Mission of San Antonio de Valéro, and so was built on the battlegrounds of the Alamo. The plaza was largely under construction during our trip as a new Alamo Museum is being built. I was struck to find the street we crossed the last time we visited the Alamo was gone, replaced by a fully pedestrianized Alamo Plaza that will certainly improve the vibrancy of the neighborhood once the work is finished. Upon arrival we had lunch in the Menger Bar, famous as the place where Theodore Roosevelt gathered many of the men who would sign up to join his Rough Riders in 1898 to go fight in the Spanish American War in Cuba. The bar and the hallway just beyond it are full of T.R.’s relics.

The Menger was host this year to the annual meeting of the Society for the History of Discoveries (SHD) which met alongside the Texas Map Society. I didn’t attend the Texas Map Society meeting on Thursday, instead choosing to go tour the missions with my Mom but was delighted to get to meet the other members of the SHD who I only knew to that point through our email correspondence. I presented on Saturday morning, mine was the first paper to be read that day. In my paper, I discussed how André Thevet tried to synthesize eyewitness testimony from two other explorers: Antonio Pigafetta’s account of Patagonia and Francisco de Orellana’s account of Amazonia with his own account of Brazil to create a full cosmography of the Americas as they existed at the time he wrote his Singularities of France Antarctique in 1557. In the sixteenth century, the word cosmography referred to the amalgamation of cartography, ethnology, geography, and natural history to craft as full a narrative about the known world as possible. As a part of my dissertation research, I translated Thevet’s Singularites from Middle French into Modern English and am now applying for postdoctoral fellowships that can help me finish the job of preparing to submit my translation for publication by an academic press.

I truly loved my time in San Antonio this Fall, and like the other two cities I visited for these three conferences I would’ve been happy to spend more time there. On Saturday evening, we drove north to Austin to see friends who I hadn’t seen since the recent pandemic. I was struck by the stark differences between San Antonio, the old Tejano city, and Austin the gleaming new metropolis driven by tech money. Still, on Sunday, 27 October we returned home on the only direct flight you’ll hear about in this week’s edition of the Wednesday Blog. I had two days at home, during which I worked both days, before heading out again.

Toronto

This time, I traveled to the Great Lakes region and back to one of my favorite cities that I hadn’t been able to visit since 2019. Toronto is not only the largest city in Canada today, it is also like San Antonio a crossroads, yet this is a place where Canada, the United States, and the many immigrant communities with ties to the Commonwealth and the old British Empire meet. I’ve often thought of Toronto as a city similar to my original hometown of Chicago, just cleaner and with a very different set of immigrant communities owing to Canada’s longer connections to Britain and the Empire than our own. I had a 4 hour connection in Chicago at O’Hare Airport, during which time I walked the full length of Terminals 1, 2, and 3, a good 5 km at least to pass the time. Terminal 1 retains its fine 1980s architecture, the soft whites, blues, grays, and blacks from its tile floor and steel frame still as it always has been. Terminals 2 and 3 however need some work. I was struck by how dark and drab Terminal 3 seemed; this is actually one reason why I fly on United instead of American, I would rather connect at O’Hare in Terminals 1 or 2 than in Terminal 3 just for the nicer architecture of Terminal 1.

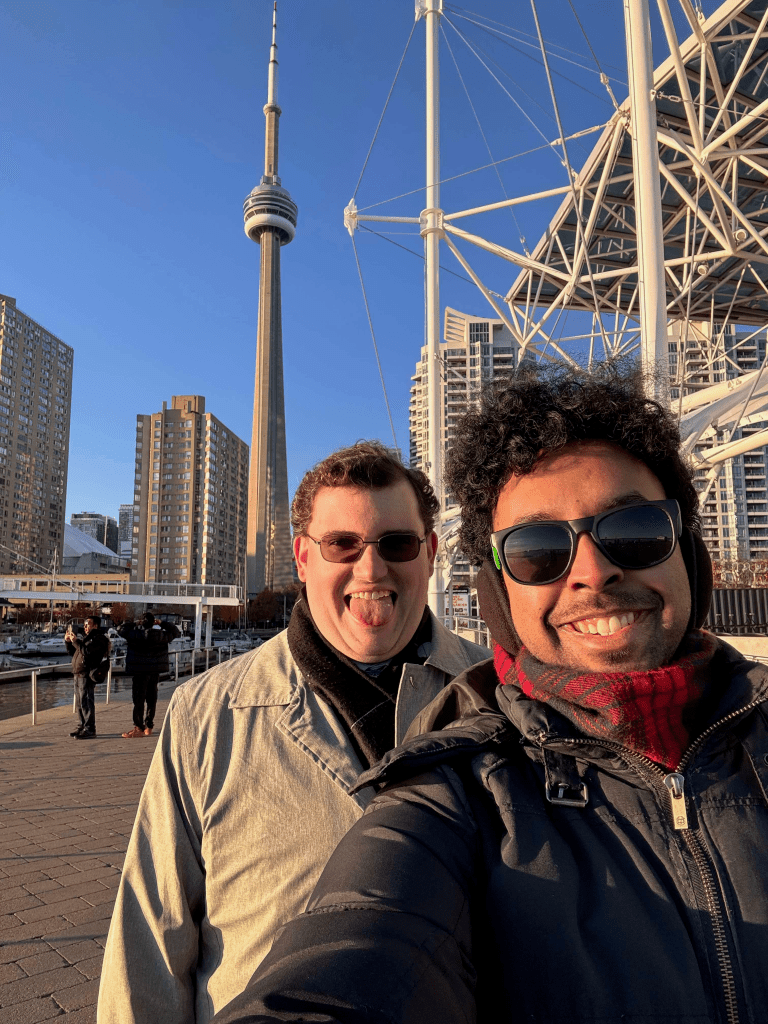

I arrived in Toronto later in the evening on Wednesday, 30 October and took the UP Express train from Pearson Airport into Union Station, near which I was staying with a friend, Hariprasad Ashwene. Toronto reminded me more of Austin with its gleaming towers, though that is more of the North American standard that the urban core should have skyscrapers to make the most of what little land is available. The biggest thing about that city which struck me was that compared to my previous visit almost 5 years to the day beforehand, was how much warmer it was there. The last time I’d walked through Queen’s Park at the end of October it had been snowing. This time though, I only had to wear the sweater I’d brought on the last day of my trip when the warm weather that our continent had basked in began to fade. On the day I landed, Kansas City experienced its first rain in nearly 2 months, yet that rain came with high winds, thunderstorms, and tornadoes across the Great Plains and Midwest and resulted in both of my flights that day being quite bumpy with hard landings across the board.

These are all clear signs of climate change, and it baffles me that we aren’t doing more about it. This trip, just like the San Antonio one, would have made a decent one by high speed rail. From Kansas City I would’ve again connected in Chicago before heading northeast to Toronto via Detroit. As it stood, I saw my second flight fly over the Ambassador and Gordie Howe Bridges connecting Detroit with Windsor, Ontario on that northeasterly route. To San Antonio, it would’ve required a connection probably in Fort Worth which seems to be Amtrak’s big future Texas hub based on the Federal Railroad Administration’s (F.R.A.) Amtrak Daily Long-Distance Service Study released in March of this year.

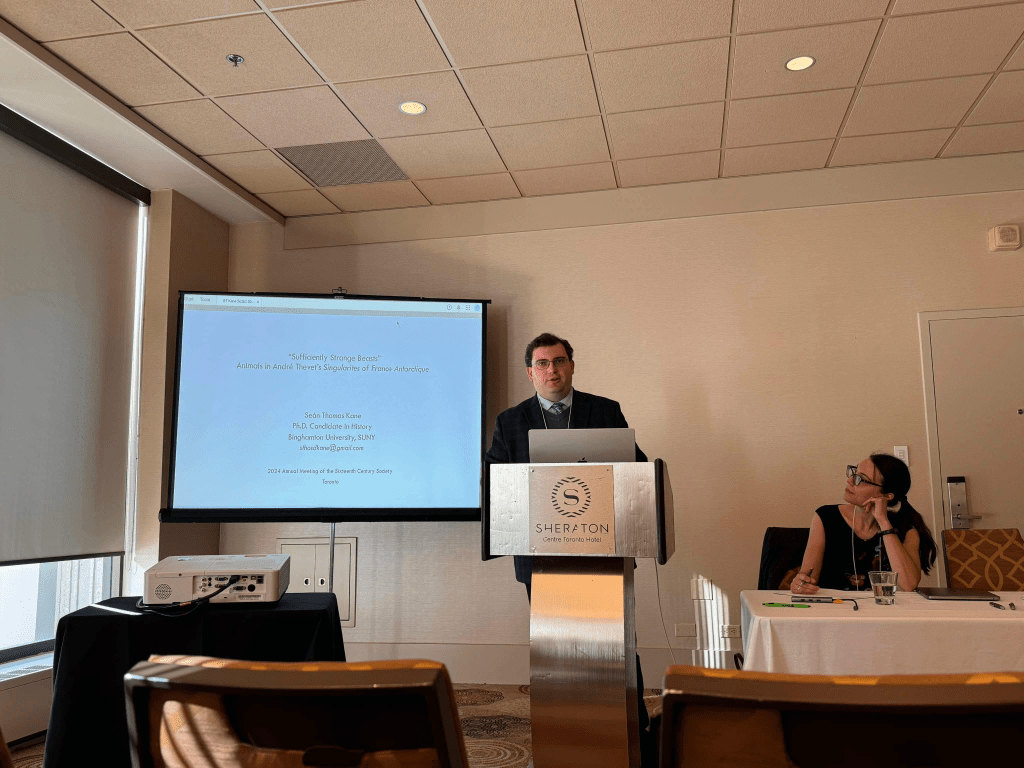

I traveled to Toronto to participate in the annual meeting of the Sixteenth Century Society (SCS), the one conference that I’ve attended year in and year out the longest. My first trip to the SCS was in 2019 when we met in St. Louis. That was also the last conference where I presented research derived from my History Master’s thesis written at the University of Missouri-Kansas City (UMKC). This time, I was presenting a very similar paper to the one I’d presented in San Antonio, only instead of looking at Amazonia and Patagonia I turned to specific animals which Thevet described in his Singularites that he himself did not see and try to trace the origins of what he wrote.

The first of these two was the manatee (Trichechus manatus), which Thevet described living in the Florida Straits. His manatee account was drawn directly from the one that appears in Book 13 of the Historia General y Natural de las Indias written in 1535 by the Spanish naturalist Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés (1478–1557). The second was an account of a wild and hairy American bull, what we today know as the American bison (Bison bison) which Thevet drew from Giovanni Battista Ramusio’s (1485–1557) recounting of Oviedo’s recording of the Relación written by the conquistador Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca (c. 1488–1559). Cabeza de Vaca was one of only a handful of survivors of a failed Spanish expedition to explore and claim territories north of New Spain in the deserts and mountains of the Mexican-American borderlands. In San Antonio then I was delighted to hear a presentation given by a professor at Texas A&M Corpus Christi and one of his former students, a local high school history teacher earning his Ph.D. at the same university in secondary education, about a course the professor taught on Cabeza de Vaca’s travels in Summer 2020. I spoke with the high school teacher the following day about my own presentation that was coming up the following weekend in Toronto whether I was correct in placing Cabeza de Vaca’s bison sighting in South Texas near Corpus Christi Bay along the Nueces River. He did confirm that it was a probable place where that could’ve happened, and so armed with this new affirmation I gave what became one of my best public talks to date at the SCS. It turned out though that I missed one link in the chain, for Thevet’s bison picture originated in the 1555 Cronica de la Nueva España written by Francisco López de Gómara (1511 – c. 1566).

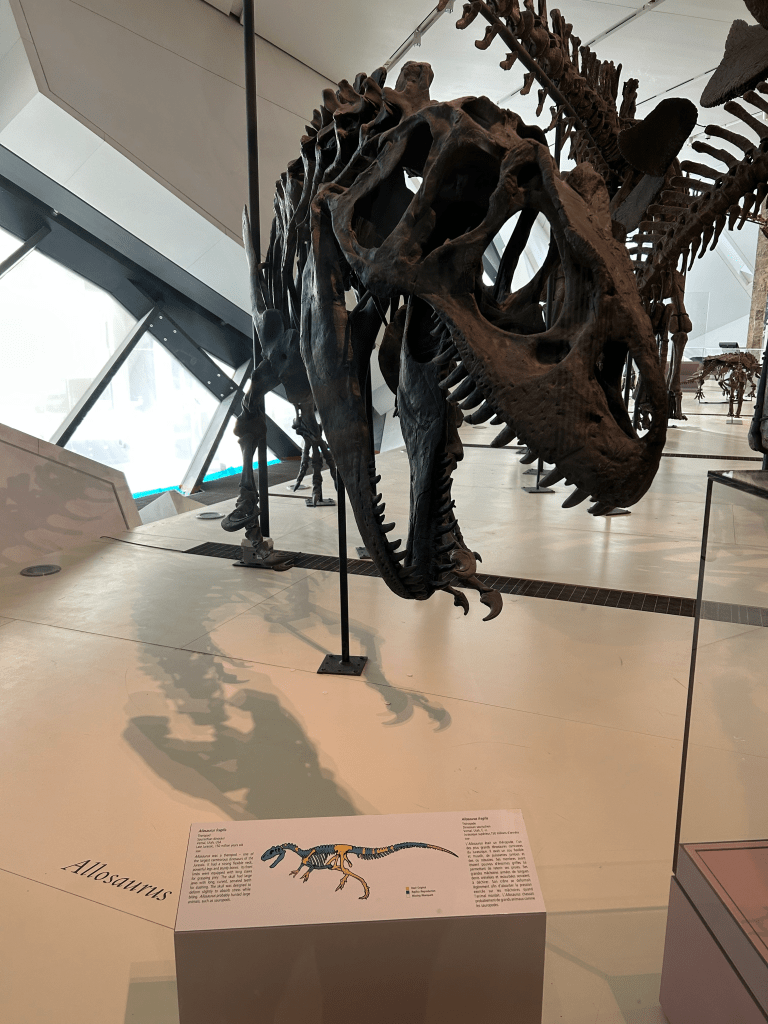

While in Toronto I took some time to enjoy that city. I visited the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) on the morning of All Saints’ Day, the Friday of that week. The ROM is in my opinion one of the better museums in North America, and a good marriage of natural history with human history and archeology. I like how if you climb the stairs there you have to go past the paleontology and zoology portions to get up to the galleries exhibiting artifacts from human cultures past and present. It really demonstrates that we are all a part of this same natural world, no matter how unnatural our inventions may become. On Saturday, before my talk Hari Prasad and I visited the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO), where the medieval and early modern European art and Canadian art are the two main highlights. That afternoon after presenting we spent a good bit of time walking along the lakeshore and seeing some of the natural beauty of that city. Lake Ontario is far narrower than Lake Michigan, and so whereas you can only really see the opposite shore from the top of the Sears, now Willis Tower, you can see Niagara and Upstate New York from the tops of Toronto’s highest lakefront towers, as they are just under 100 miles (161 km) to the south. I ate a lot of poutine in Toronto, though less than the last time I visited. I even tried a poutail from the ice cream shop called Beaver Tails on the Harbourfront, which was poutine placed atop a frybread baked into the shape of a beaver tail. It was good, though it did attract a large audience of birds.

My Torontonian visit was about the right length, and in the circumstances of the world as they were that week where my mind was less on the current moment in Canada and more on the next trip to Mexico and the election due to be decided in the days in between I was ready to be home.

Mérida

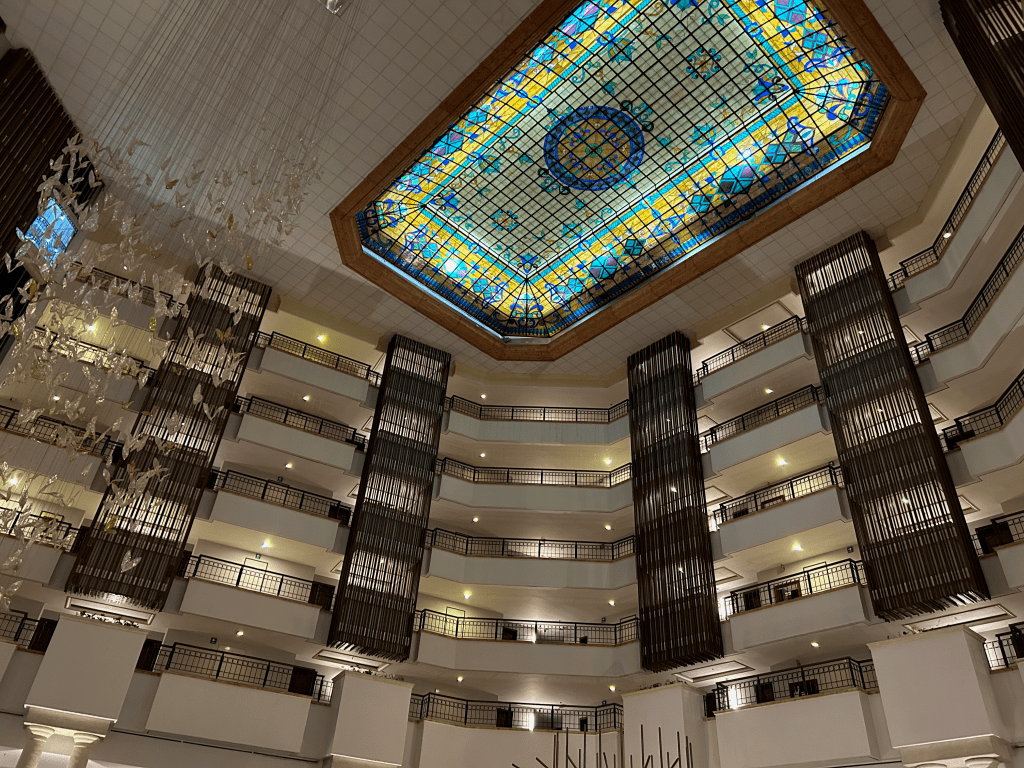

I left home again at 5:00 am on Wednesday, 6 November, knowing the overall result of our elections had taken a sorry turn that will only be fully understood after these next four years are over. Because of the result I didn’t want to travel that morning, rather I wanted to stay home and close to my family. I was distraught and in no mood for another adventure. Yet an adventure is what was in store, and I took the first flight out of Kansas City on United to Houston’s Bush Intercontential Airport at 6:30 that morning. I’m not sure if it’s because of the flight schedules between Kansas City and Houston on United or if it’s because of the ones between Houston and Mérida but I had excessively long connections on both my outbound and return flights on this trip. On the way out, I spent 8 hours in the United Club close to the gate where my Mérida bound flight left from that evening. I was delighted to see several familiar faces on my Mérida flight, a good half if not 2/3rds of the passengers on that flight were fellow historians on their way to the History of Science Society’s centennial conference at the Fiesta Americana Hotel in Mérida.

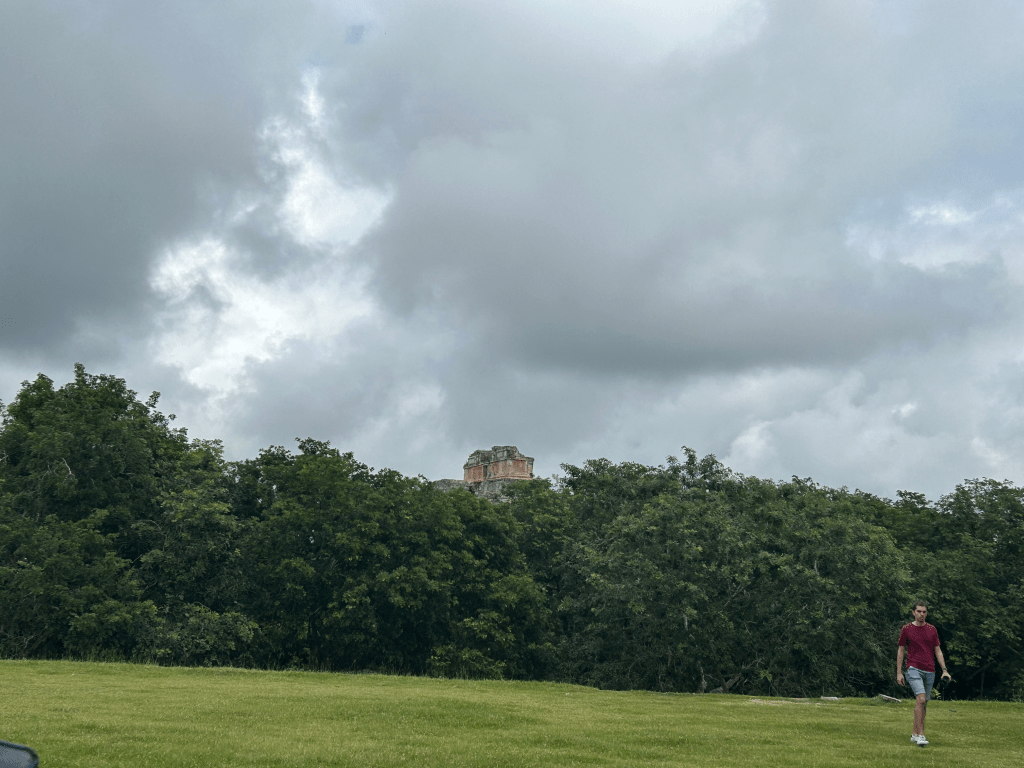

After we landed my inadequacies in Spanish made themselves well and clear from the first moment. I gave the driver who picked me up at the airport the wrong address, and ended up at a hotel 2 miles (3 km) from where I was supposed to be. I ended up getting an Uber to take me to the correct place, arriving there close to 21:30, and was able to get dinner from the hotel kitchen by 23:00. Exhausted, I had a quick sleep before waking early around 06:00 and walking the 5 minutes north to the Fiesta Americana where I exchanged 45 dollars for around 850 pesos, got breakfast, and met more people who like me were going on the Thursday tour of the Mayan city of Uxmal, whose ruins are about 45 minutes drive-time to the south of Mérida. Mérida is a Spanish colonial city built atop an older Mayan city named Ti’ho. The Cathedral of San Ildefeonso in the city’s central plaza was built using stones from the older Mayan pyramids that were once found here.

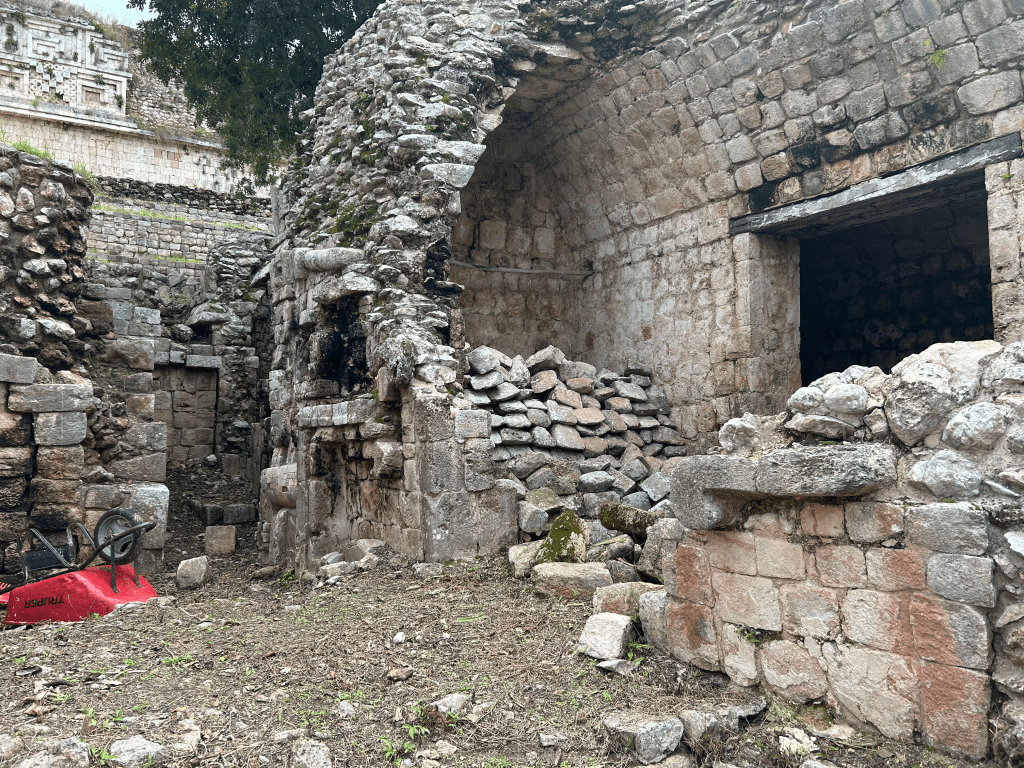

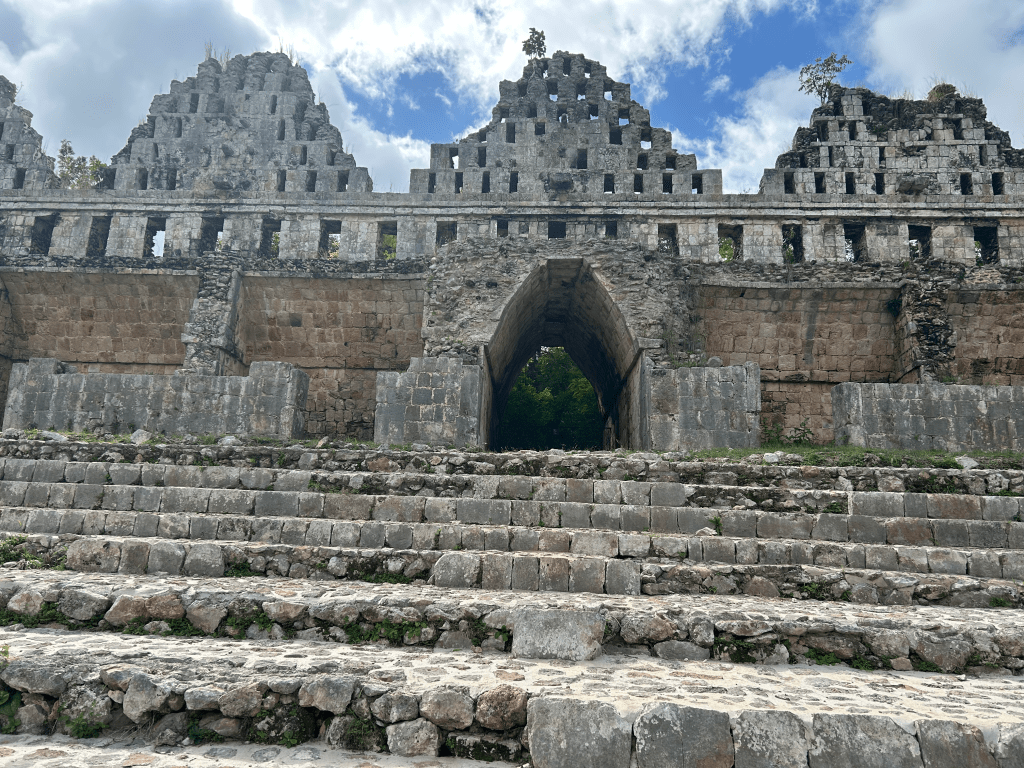

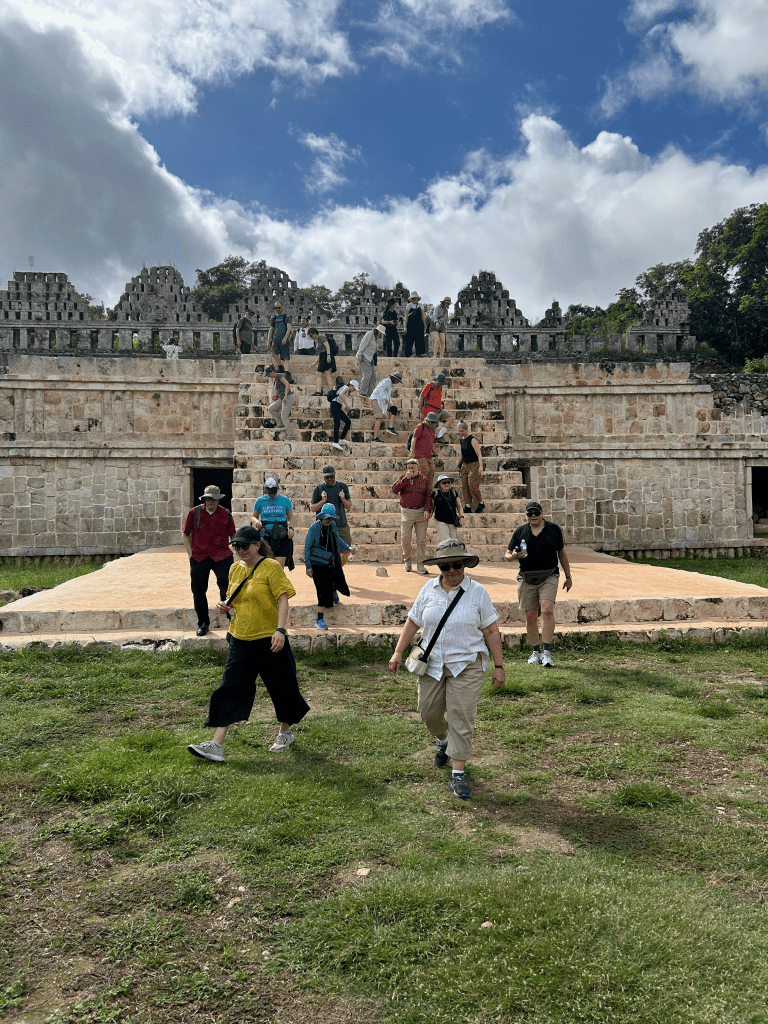

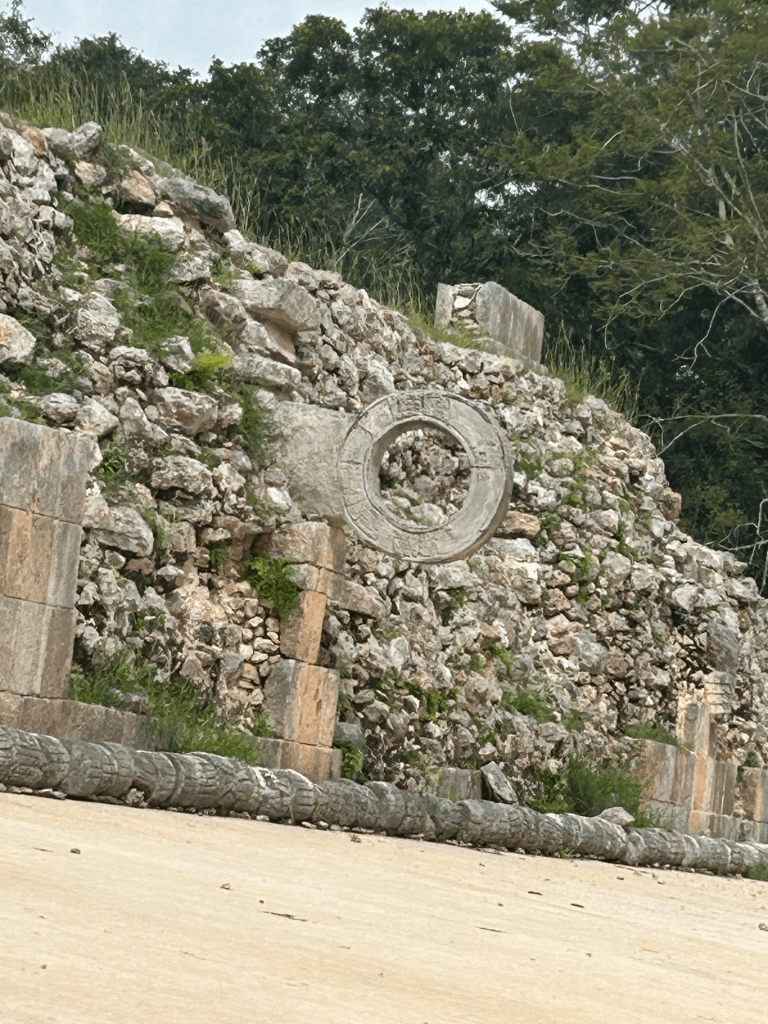

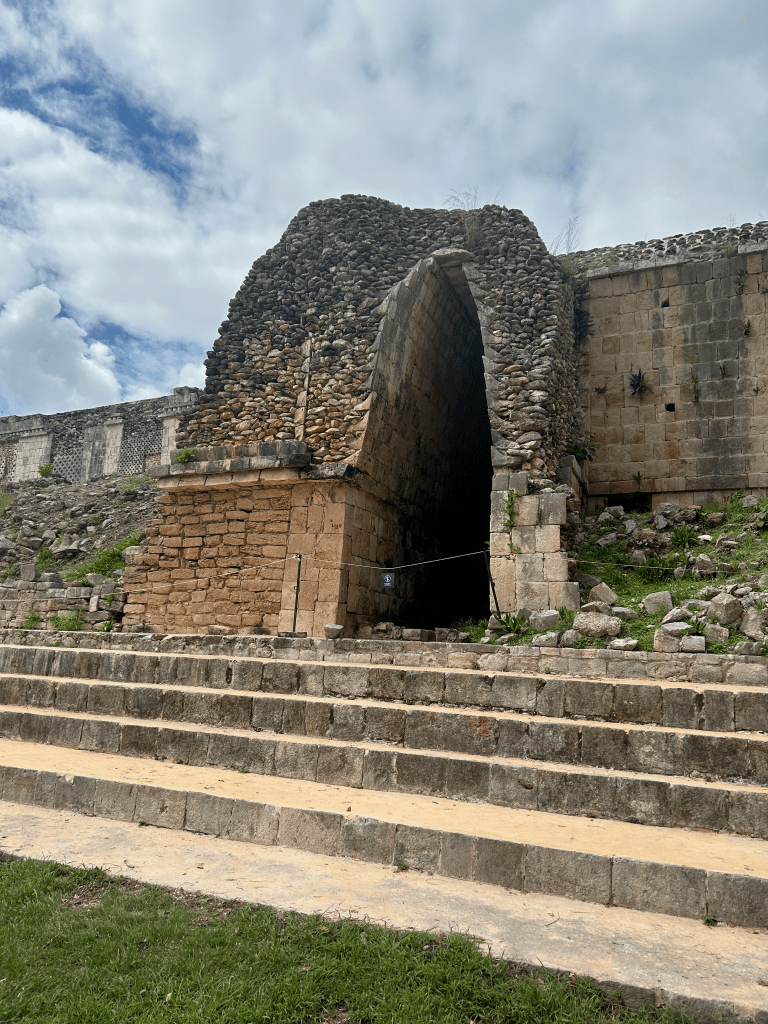

South of Mérida, Uxmal was a fascinating place to visit. This city once housed around 30,000 people, and its pyramids still rise above the jungle canopy. It was all that I hoped it would be and more, a monument to the ancestors of the people of the Yucatec Mayans who are still the majority population in the Yucatán State and in Mérida, its capital. The tour started with the Pyramid of the Magician, the great central monument of the site, after which we walked past the Palace of the Governors, and then to the High Pyramid and the South Pyramid before descending down the steps of the latter and walking to the Ballcourt dedicated in the year 901 CE by the city’s king Chan Chak K’ak’nal Ajaw where the old Mesoamerican ballgame was played. The pyramids here have a rounder shape than those at Chichen Itza, and the Pyramid of the Magician seems to be a series of temples built one atop the other.

I spent most of my time in Mérida either at the Fiesta Americana or at my hotel in the Paseo 60 complex, a few minutes’ walk to the south. I’d intended to venture out to visit some of the city’s museums, including the Gran Museo del Mundo Maya and see the older Spanish urban core, including going to Mass at the Cathedral, but as it happened after returning from Uxmal I didn’t get very far from the conference. This was my first visit to Mexico, and there was a lot there to get used to that was different from any other country I’ve yet been to. I was struck by how affordable everything was compared to the United States. At the time 1 dollar would get you about 20 pesos, and in general everything was much cheaper than in San Antonio or Toronto let alone in Kansas City. Still, seeing prices listed in hundreds and thousands of pesos was a bit of a shock to me at first. I was very careful to not drink the water, using bottled water to brush my teeth, and keeping my mouth shut tight while showering. Where in San Antonio and Toronto there was water available in pitchers for us to pour into our own glasses and bottles, in Mérida there were bottles of water at every break alongside the coffee and pastries. Yet beyond all of this the one thing I was most worried about among all the usual domestic concerns was the inability of the plumbing to take flushed paper. This turned out to be less of an issue than I expected, though for the sake of the sanity of this post I’ll leave that topic be.

This was my first visit to the History of Science Society’s (HSS) conference, and it certainly won’t be my last. I reconnected with several people who I’ve known off and on over the last five years in my doctoral studies and met many more people whose work I found fascinating and whose company I greatly enjoyed. I attended more sessions at this conference than at the Sixteenth Century Society, in part because two of the sessions I planned on attending at the SCS were cancelled. Perhaps this speaks to a stronger presence of early modern historians of science in the HSS than at the SCS, both conferences compete with each other as their meetings happen at the same time of year, opposite to the Renaissance Society of America’s annual conference in the Spring. Still, when I left Mérida, I found myself sad to leave these people, colleagues and friends, who I’d gotten to know in a few short days.

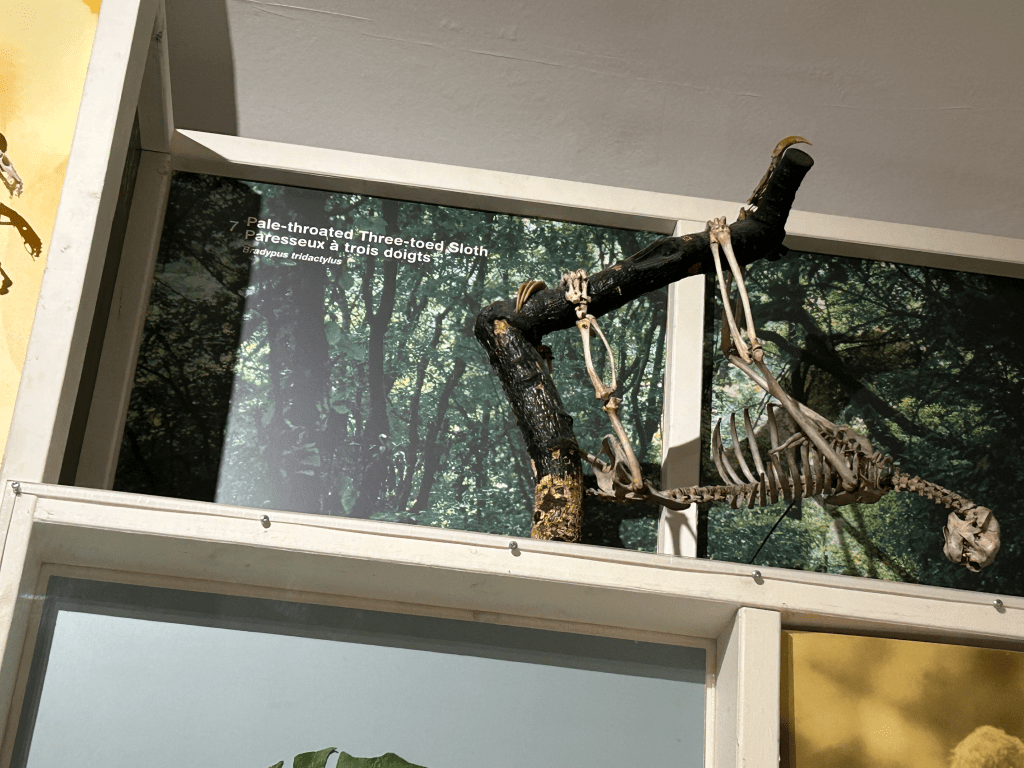

At the HSS, I presented a paper drawn from Chapter 3 of my dissertation which summarized my argument that Thevet’s eyewitness description of the southern maned sloth (Bradypus crinitus) reflected the gradual shift in the sixteenth century from humanism, a discourse centered on established learning from antiquity, toward the scientific developments of the seventeenth century. This then was my only presentation among the three conferences that was drawn from my dissertation rather than the introductory essays for my translation of Thevet’s Singularites. The SHD and SCS papers will likely end up in the same essay as they cover very similar topics to the point that in moments in between conferences when I’ve attempted to explain what each of them were about, and I couldn’t remember one or another of them. That however speaks as much to the number of presentations I was giving in short order: I knew I had the papers written, printed, and placed in the correct file folders and that the slides were ready to go. All I needed to do was run a couple of rehearsals beforehand and then read the papers on the day of. What ended up happening was a bit different, following from advice I received earlier this year I tried going off script a bit more than usual. At the SCS this worked really well, though I did end up going 3 minutes over my allotted 20. Meanwhile at the HSS, knowing I only had 15 minutes to present and that the recurring technical problems during our session had taken a minute or two from the presentations, I decided to end mine early cutting some comments about the philosophy of animal behavioral psychology that I’d brought in from David Peña-Guzmán’s book When Animals Dream: The Hidden World of Animal Consciousness.

Houston

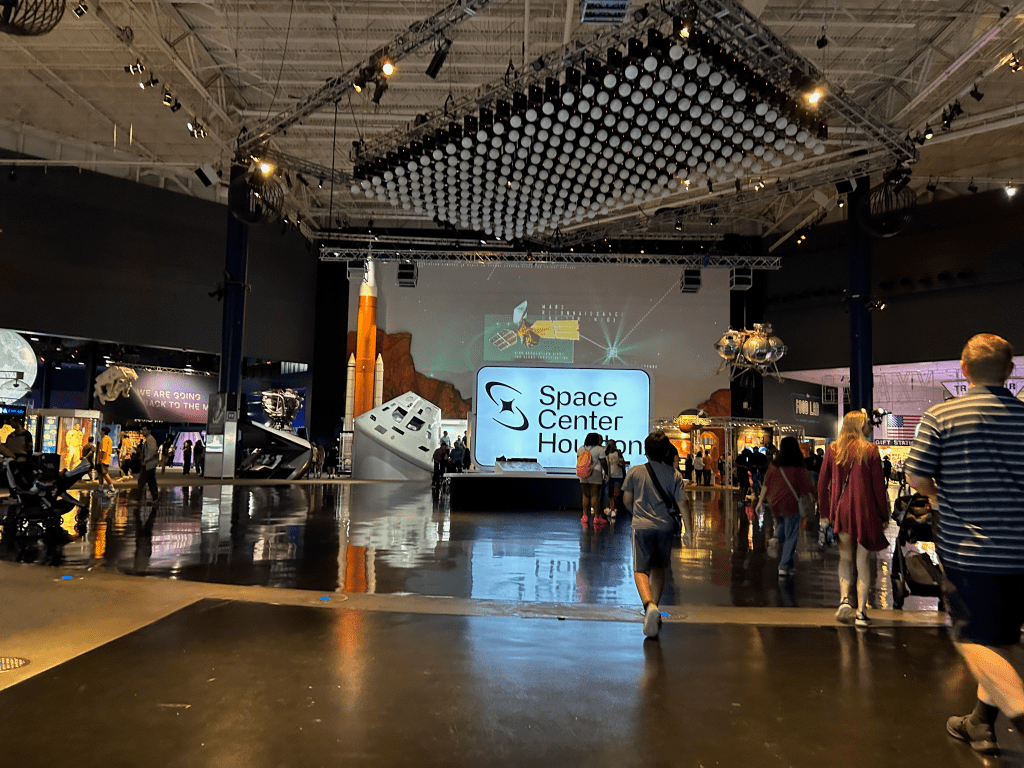

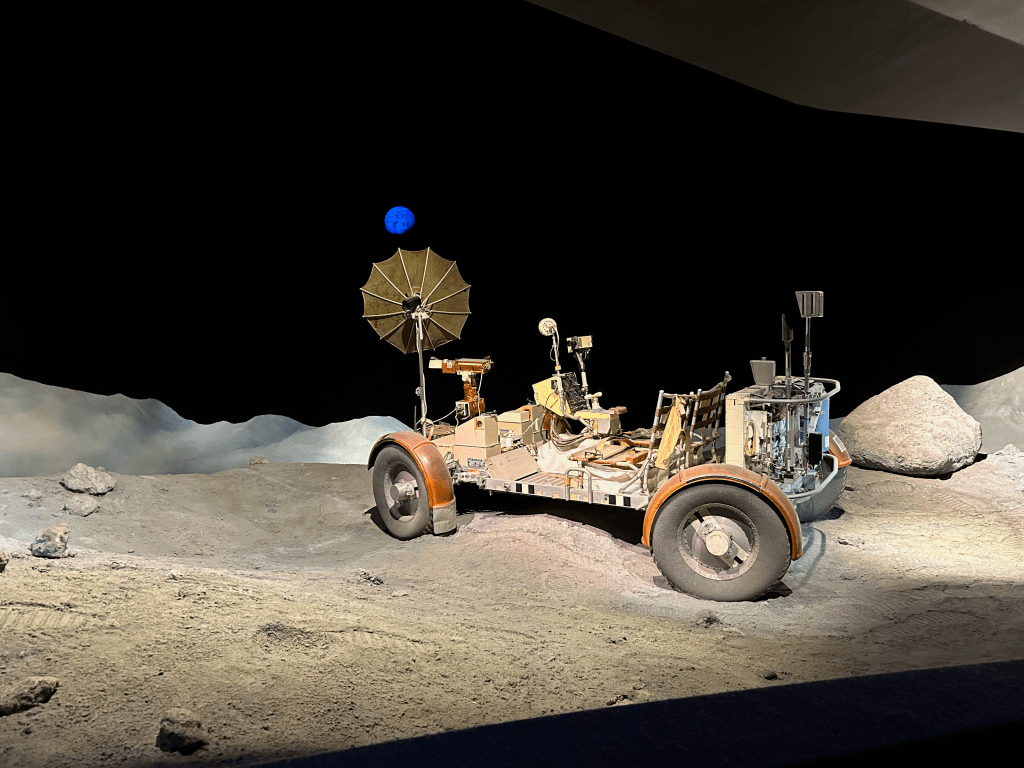

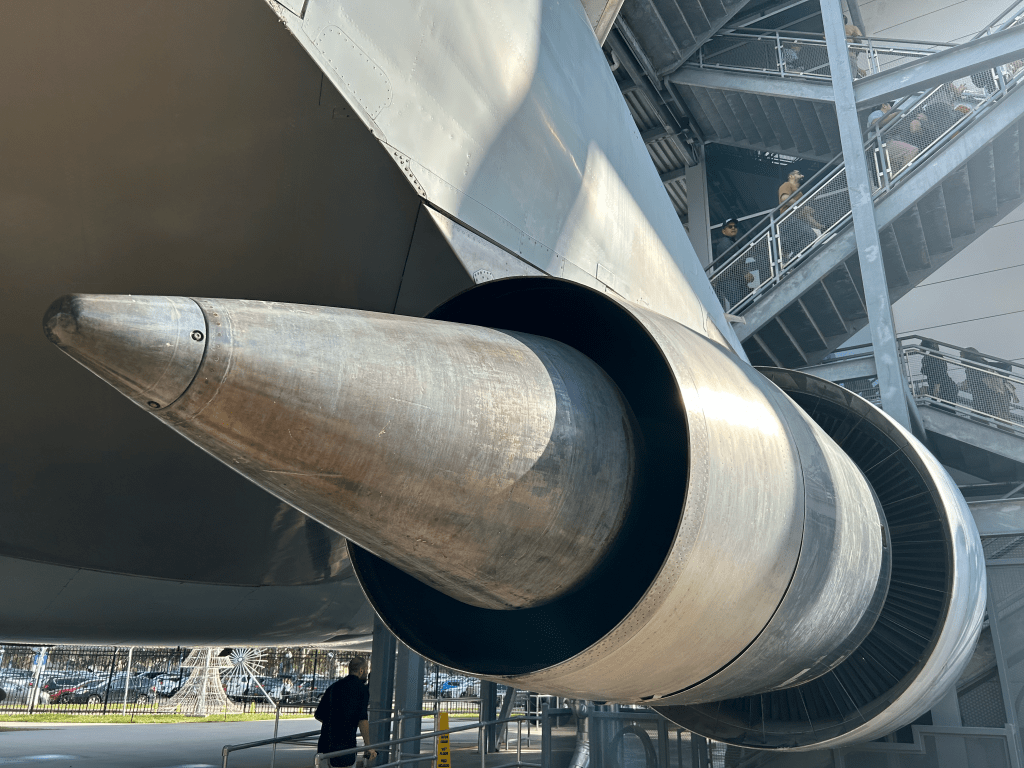

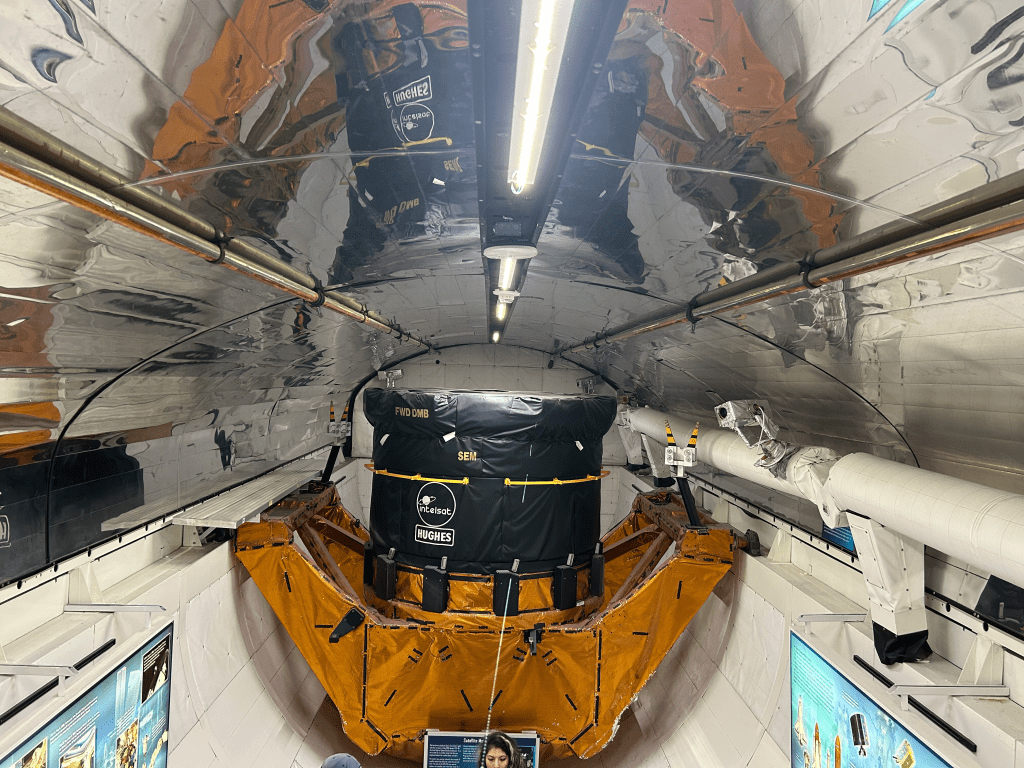

On the way home from Mérida I had an 11 hour layover at Houston Bush Airport again, and this time instead of staying in the United Club and working I decided to take the day to visit the Space Center Houston, the visitor’s center next to NASA’s Johnson Space Center. At the beginning of the year, I looked into visiting the Space Center and booking a VIP tour of the International Space Station’s Mission Control Center, and had the trip planned out and at a reasonable price but still ended up choosing to not go to save money, a wise decision seeing how 2024 has turned out. So, on Sunday, 10 November I rented a Volkswagen Jetta from Hertz and drove across Houston to the Space Center. It turned out to be a marvelous place to explore, at times in spite of the crowds of which there were more than I expected. My only comparisons to this are visits to the Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum in Washington and to the Kennedy Space Center Visitor’s Complex in Florida. The former is far more the museum like Space Center Houston, both very busy, while the latter is more like the other Central Florida theme parks, albeit a government owned theme park dedicated to space exploration.

I arrived close to 12:30, a good 2 hours after landing, and was at first taken aback by just how busy the place was for a Sunday at midday. One part of that was that the Houston Texans weren’t playing until later in the day, which meant more locals and tourists for the visiting Detroit Lions were taking the midday hours to do some sightseeing. My first stop in the Space Center was the Artemis gallery displaying all things associated with NASA’s international program to return humans to the Moon for the first time since Apollo 17 landed in December 1972, almost 20 years to the day before I was born. There was a board where NASA invited members of the public to leave questions for the Artemis II astronauts, who are due to launch for the first crewed lunar orbit of the program no earlier than September 2025. I usually avoid these sorts of things, in a similar vein to why I like to avoid clicking on the ads on Google or any of my social media sites solely out of the enjoyment at seeing the big guy not getting my vote by engaging with their stuff. This time though was different, because as I’ve written before here on The Wednesday Blog, I worry that we may be going to Space for the wrong reasons: for profit, or glory, or conquest rather than for curiosity, or exploration, or hope that we might learn more about ourselves in finding what’s out there. My question then was this:

“How do you hope the Artemis missions will inspire humanity to become better versions of ourselves?”

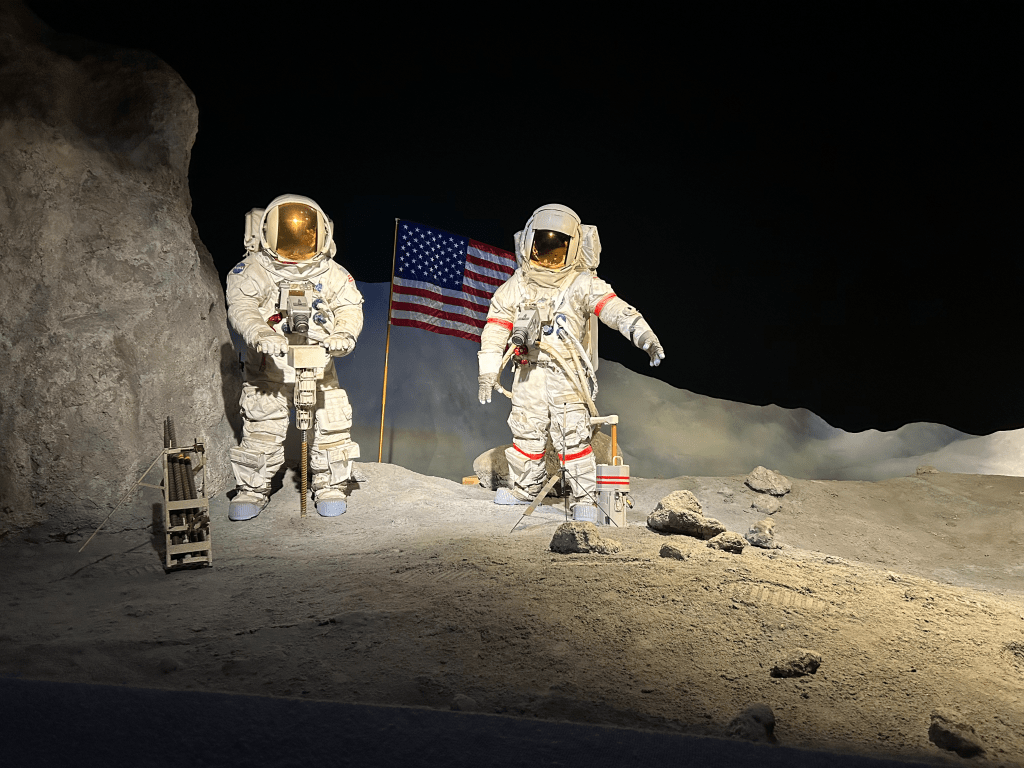

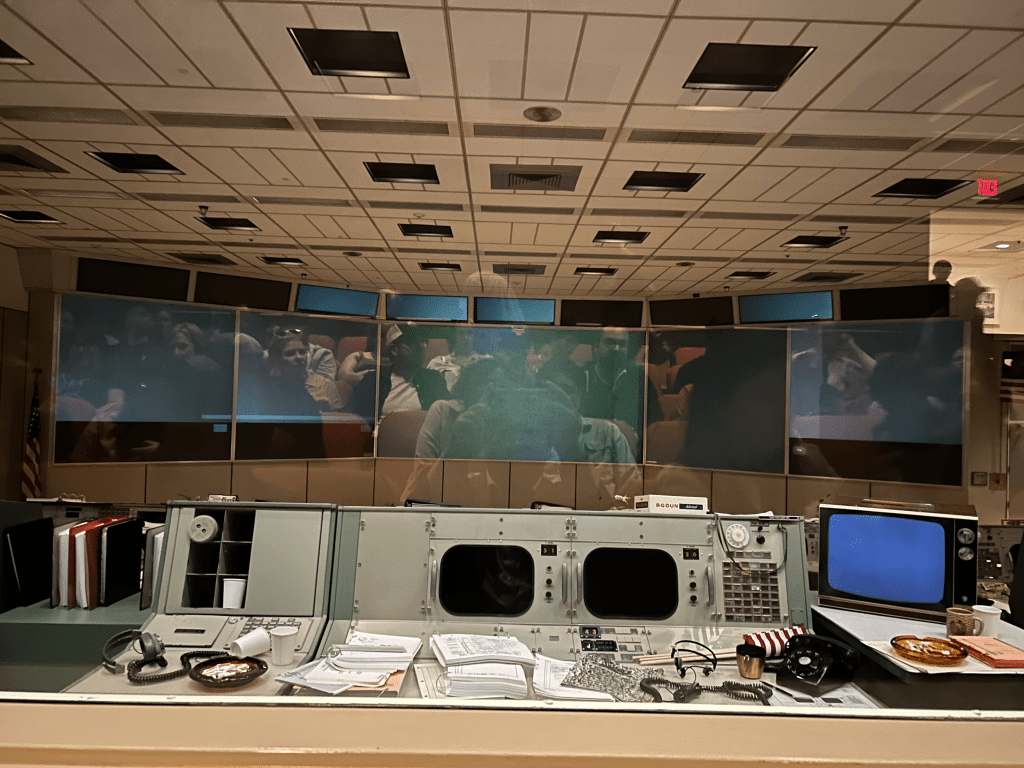

This speaks to something that’s at the heart of what I do, of why I study the history of sloths in the 1550s. In that study I hope to find something about how Thevet interacted and reacted to the sloth he observed for 26 days that can tell me more about how he fit that sloth into his understanding of nature as a whole. In it beyond the study though, I hope I might learn something more about how to better interact with unfamiliar people, creatures, and things that I encounter in my life. Travel is the search for new things to know to enrich our lives by that experiential learning we do. The highlight of my visit to Houston on Sunday was touring the rooms that house the Apollo Mission Control Center where the first contact between our first human explorers to set foot on another world were first received by humans here on Earth. I know this room all too well, in fact I wonder if my fondness for the white tile aesthetic that I used to see in grocery stores or even some school classrooms isn’t in fact drawn from fond memories watching recordings of those TV broadcasts from 20 July 1969 when Apollo 11 made its landing on the lunar surface. I learned years ago to keep my camera out of my hands for most of my life and to let myself experience these moments that I have with my own eyes, and so while I did take 11 photos of the Apollo Mission Control Center while in the viewing gallery, I refrained from switching my camera to record video of the experience like many around me did. I’d rather remember those moments spent watching as the critical moments of the Moon landing played out in front of me and preserve them, however imperfectly, within my own memory that those moments get tinted with nostalgic yellowing like old paper as they age. I in fact found myself looking around Mission Control searching for all the parts of it that I know from the Apple TV+ show For All Mankind, which is one of my favorite new shows of the last five years and features Mission Control as one of its primary settings.

At the end of the day, in spite of any other troubles or annoyances that beset me, and there were some of those, I was still happy that I took the opportunity to visit the Space Center and see where one of the great vehicles of hope that remain in these dark years does its work. We may find that our best solutions to our climate crisis and to the multitude of human crises from our nigh insatiable greed or our unholy cruelty we inflict upon one another and ourselves may find a balm in reaching out and exploring our Solar System and those of other stars. I’m an optimist, even if my optimism is covered by all the debris of our pessimistic time. I hope that when Artemis II successfully orbits the Moon, and Artemis III lands humans on the Moon to establish the first lunar permanent outpost of our species that we will celebrate these accomplishments as things undertaken for all humanity and not for one nation or tribe. Our troubles today, I hope, are signs that we are beginning to move out of what Carl Sagan called our adolescence as a species and into the years when our future will really begin to look bright again.

In spite of all these troubles, this North American Tour gave me reason to hope that my future, and our future as a whole, has such great promise and opportunity if only we keep working for it and never give up the fight.