Why André Thevet? – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

This week, the second in several scribblings about my research: why I chose to study André Thevet and build my career on the mound of his works.

I initially chose to focus my dissertation on André Thevet (1516–1590) because of his account of the sloth and because he was French; I speak the language and therefore felt I would not need to learn another language to grasp the sources. Thevet is a figure who I’ve gotten to know over the last 6 years. I first encountered him in Dr. Bill Ashworth’s Renaissance seminar at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. It was in a nice classroom in the southeast corner of the third floor of Haag Hall that welcomed in the midday light as the Sun arced across the sky. We met on Tuesdays and Thursdays, and often I would walk to class from my job working at a cheese shop, the Better Cheddar, at 49th & Pennsylvania on the Plaza. What I didn’t admit at the time but have freely regaled friends and family since is that on Tuesdays the shop’s sommelier would often stop by to offer those of us working at the time wine tastings of the latest vintages. I was hired by the cheesemongers there more for my knowledge of European wines, and because I spoke French, than for my far more limited understanding of cheese going into the job. So, I often went from a delightful morning tasting cabernet francs, pinot noirs, and syrahs to a delightful afternoon sitting in the back third of Dr. Ashworth’s class listening to his stories about the Renaissance.

By this point, I was still committed to a largely unfounded master’s thesis project studying crypto-Catholics in the English court of James I and VI, which was born out of a desire that I might find my way back to London perhaps to work as a curator at the Banqueting House or Hampton Court. By Christmas, that project had well and truly died, it was only several years later that I discovered the fantastic work of the late Professor John Bossey on persistent Catholicism in the North of England that I found the anchor and line that would’ve led me toward my original research project idea. As it turned out, I found my way to Thevet through a more traditional Renaissance history master’s thesis about English humanism, specifically the education of Margaret Roper (1505–1544) and Mary Basset (c. 1523–1572), daughter and granddaughter of St. Thomas More (1478–1535). As an English-speaking Catholic of mostly Irish descent, with a fair minority of English ancestors to boot, I was drawn to the More family as models of a Catholic conscience; it is rather fitting that the upsurge of English colonialism in Ireland coincided with the English Reformation. When I lived in London, while I usually attended Mass at the Jesuit church at Farm Street in Mayfair, I would occasionally go to the English Chant Mass at Westminster Cathedral near Victoria Station. All of this came together in my History master’s thesis about Roper and Basset, my second thesis after the one I wrote in London for my degree in International Relations and Democratic Politics at the University of Westminster.

Yet while I was working on this and writing good essays and papers, I kept hearing my friends talk about how the classes they loved the most dealt with the History of Science. One of my greatest regrets from my time at UMKC is that I didn’t take Dr. Ashworth’s Scientific Revolution class. It would’ve proved to be a good foundation considering I’ve taught essentially the same material since, and considering a great deal of the effort of my generation has been focused on deconstructing this perception of a revolution from humanism to science at the turn of the seventeenth century. So, when I discovered to my horror two weeks before leaving Kansas City to begin my doctorate at Binghamton that the thesis of the dissertation I intended to write had been published in a peer-reviewed journal a year before I took the chance to shift gears entirely and dive into the history of science. I used Thevet’s sloth as my diving board.

I met André Thevet in August 2019. We’d been introduced three years before by Bill Ashworth, yet besides the chuckles I gave at seeing his sloth engraving for the first time I turned my mind away from the Franciscan. Through Thevet I was introduced to the Renaissance notion of cosmography, a starkly different use of the term than how I’d heard it. To me, cosmos is most synonymous with Carl Sagan’s book and documentary series, including that series’ remake in the last decade by Neil DeGrasse Tyson and Sagan’s widow Ann Druyan. I kept coming across the word cosmos throughout the years I was in Binghamton in a myriad of windows. On all of my long drives I listened to audiobooks, and I usually remember the books better than the drives themselves. They animated my existence for those days in the Mazda Rua, my car, crossing the eastern half of our country by road. The first day of my August 2021 Long Drive East was so animated first by Alex Trebek’s last book, which he and Ken Jennings co-narrated, and second after I finished that book on I-70 near the Indiana-Ohio border I turned on a reading of Sagan’s Cosmos read by LeVar Burton. I stopped the car at the Ohio Welcome Center, maybe an hour into the book, to try and get another stand hour on my smart watch and was struck at how brilliant the sky above me seemed that clear August night. That day I’d been running from a massive storm that bore down on Iowa, Illinois, and northern Indiana, a derecho, and for the first time all day I couldn’t see the dark billowing clouds with bolts of lightning shooting forth like thanatic trumpets reminding all in their path that we are mere lodgers on this continent owned by Nature itself. Yet in that moment there were no clouds, no storms on the horizon, only stars burning high above.

In another drive on a Sunday in late September 2022, at the end of a delightful weekend I spent with my friend Alex Brisson in Ticonderoga and Albany, I drove southwest through the rolling hills of Central New York toward Cooperstown to visit the Hall of Fame. While I was driving, I listened to Andrea Wulf’s biography of the Prussian naturalist Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859). On that particular Sunday, I listened as Humboldt’s own book Kosmos was described in depth. It felt to me that I could see some of the inspiration for Sagan’s Cosmos in Humboldt’s magnum opus, and I was left wondering how Thevet’s own Renaissance cosmography fit into this cosmic lineage. As it turns out, Humboldt was familiar with Thevet’s work, and didn’t care for it at all. The Prussian naturalist is one of the earliest figures in my dissertation’s secondary literature, and he is important because he largely dismissed Thevet’s contributions to natural history writing that his vision of the cosmos was too small to warrant that word.[1] In many ways, my approach to Thevet has always been bi-directional: I’ve tried to learn more about the man by finding the books which survive from his library and the books we know he translated while at the same time I’ve always had an eye on Thevet as a starting point for understanding a specifically non-Iberian understanding of the development of the natural history of the Americas beginning in the Renaissance. My own perceptions of natural history are shaped by my childhood introduction to this vast kaleidoscope of the human vision of the rest of nature on display in my hometown natural history museum, the encyclopedic Field Museum on the Chicago lakefront. While as a child I marveled more at the dinosaurs in their upper floor galleries, now as an adult I prefer to spend my time in the museum among the taxidermy and dioramas with one eye drawn to nostalgic escape and the other toward scholarship; the Field Museum contains a specimen of one likely candidate for the species of three-toed sloth that Thevet described in his Singularitez. By taking this multidirectional focus on the history of natural history, on the one side starting with Thevet in the sixteenth century and on the other with Carl Akeley and the collecting expeditions launched by the Field Museum at the turn of the last century, I’ve developed a particular perspective on natural history that is visible in both wide and narrow focuses.

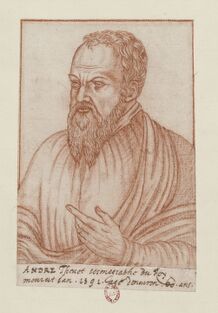

In the six years since, I felt that I not only got to know André Thevet the cosmographer but something of Thevet the man. He was just a few years older than I am when he made his first overseas voyage from France to Constantinople, the Levant, and Egypt in 1551. The most famous portraits of Thevet were published in his 1575 Cosmographie Universelle and 1584 Vrais Pourtraits des Hommes Illustres. These two portraits show Thevet at the height of his career, the cosmographer royal, the keeper of an expansive cabinet of curiosities, and a close confident of the Valois royals. Yet there’s an older portrait of Thevet as a younger man which appears in his first book, the Cosmographie de Levant, published in 1554. In it, Thevet is shown not as the resolute man of his craft but as a humble Franciscan friar. It was a position that he was put in by his father when he was 10 years old in order to give the boy a chance at a good education. I see in these three portraits something of a desire for better and greater things. In the process he crossed some people the wrong way and got a fair few things wrong in his cosmography. I’ve learned to take what Thevet wrote with a fine grain of salt especially later in his life. I wonder though if some of the acrimony that Thevet’s reputation has faced since his death in 1590 isn’t in part because of his close ties to the Valois family who declined from power and were replaced by their Bourbon cousins the year before and largely by the Valois’ infamy in the history of the French Wars of Religion, in which the Huguenots who traveled to Brazil with Thevet in 1555 were so threatened by their country over matters of faith. I recently met a woman at a Kansas City Symphony performance who was wearing a Huguenot cross necklace, and it struck me how her ancestors’ experience living as Protestants in a Catholic state mirrored my own ancestors’ experiences living as Catholics in Ireland during the Protestant Ascendancy and Act of Union with the very Protestant Kingdom of Great Britain in 1800. Like her, I’d grown up with a sense of pride in my Catholic ancestors’ resilience at staying Catholic in spite of the state which ruled over them. Seeing the long shadow of the Wars of Religion which for my people didn’t really end until Good Friday 1998 from this vantage gave me tremendous perspective. How did Thevet view it all? He blamed the Huguenots in part for the fall of France Antarctique in his Cosmographie Universelle, writing that “little of this would have happened without some sedition among the French, which began with the division and parting of four ministers of the new religion sent by Calvin to plant his bloody gospel.”[2] Why did he choose to write that the way he did? Certainly, these religious tensions gave cause for the Portuguese to eliminate the French presence in Brazil, yet wouldn’t the economic threat of the French presence in Brazil toward Portuguese trade be justification enough? Could Thevet have been responding to the political situation he found himself in when he published the Cosmographie Universelle in Paris in 1575?

I like Thevet because I find the man relatable, I get the sense that we can relate somewhat; like him I’ve felt this constant need to prove myself to my peers. This need has waned somewhat as I’m moving along with my career. Yet I feel the younger Thevet depicted in his Cosmographie de Levant is more relatable to my life today in my early thirties. While not a cleric, I chose to not go down that path, I’m alone in my life with a strong sense of wanderlust. Those wanderings have taken me to Paris twice now in the last two years to get a sense of Thevet from beyond the printed books with which I’m most familiar. In October 2023 I followed a lead which took me to Rue de Bièvre, the street where he lived at the end of his life up to his death in 1590. I walked up and down that little street between Boulevard Saint-Germain and Quai de la Tournelle and stopped in the pocket park on the western side of that street. I felt that this was the closest I’d ever get to him, after all the church where he was buried, the Convent des Cordeliers, was desecrated during the Revolution of 1789-1791 and from what I’ve been able to gather, his tomb disappeared. Yet earlier this year while watching an episode of PBS’s science series NOVA about the graves found in Notre-Dame during its reconstruction, I noticed they pulled out a nineteenth-century book of old Parisian epitaphs. I did a quick search through the BnF’s Gallica database, and found Thevet’s own epitaph there transcribed from the original stone carved in 1592 that lay in the Convent of the Cordeliers. In the original French it reads:

Cy gist venerable et scientifique personne Maistre Andre The-

vet, cosmographe de quatre roys, lequel estant aagé de LXXXVIII (88) ans, se-

roit decedé en ceste ville de Paris, le XXIII jour de Novembre M D XCII. –

Priez Dieu pour luy.[3]

In English, this translates as :

Here lies the venerable and scientific person, Mr. André Thevet,

Cosmographer of Four Kings, who was 88 years of age,

he died in this city of Paris, the 23rd day of November 1592.

God, pray for him.

On that same trip I visited a wooden Tupinambá club which the Musée du Quai Branly records was donated to the royal collections by Thevet and was given to the cosmographer by the Tupinambá leader Quoniambec (d. 1555). I figured this would be the only artifact I’d see that Thevet would’ve himself handled. Little did I realize that eight months later I’d be back in Paris, this time at the BnF’s Richelieu building in the Department of Manuscripts reading through Thevet’s own handwriting. I’d made a visit there that day to read through Thevet’s translation of the Travels of Benjamin of Tudela, a twelfth-century Sephardi Jew from the northernmost reaches of Al-Andalus which told the story of his travels around the Mediterranean world. Tudela’s wanderings took place three centuries before Thevet made his own voyage east into the Mediterranean in 1551. Here, through the window Thevet crafted with his pen over 470 years before, I was reading a story retold in Thevet’s words of events that occurred over 700 years ago. That sunny June day, I spent a few quiet moments reflecting on Thevet’s penmanship, his signature, and how familiar his writing seemed. I’ve read more of Thevet than many others, after all I’ve translated the entirety of his Singularitez, and so when I was working with his Tudela translation, I found the job was made easier by how I could recognize his voice in the flourishes of his pen. I felt that I knew the man, in spite of the centuries between us. Soon after, as I walked from the Richelieu building to a café next to the Sorbonne where I was meeting an editor for a project I’m contributing to, I reflected amid my quick steps crossing the Seine that I was walking the same streets Thevet once walked. They’d changed to be sure, but there were still monuments that he’d recognize, edifices of the Paris he knew.

I chose to study Thevet out of a drive for practicality, a quick solution to a pressing problem of finding a dissertation topic that I could move to when my original plans went up in smoke. In the years since I’ve become known as a Thevet scholar. I’ve given many conference presentations and lectures about the man and his contributions to Renaissance natural history. In fact, I’ll be giving one more on June 12th with the Renaissance Society of America’s Graduate Student Lightning Talks, sponsored by the RSA Graduate Student Advisory Committee. That talk takes a different perspective on Thevet’s sloth than any other I’ve yet given, approaching it as an example of animal intelligence. Tune in to learn more.

[1] Alexander von Humboldt, “Les vieux voyageurs à la Terre Sainte (du XIVe au XVIe siècle),” Nouvelle annales des voyages, de la géographie et de l’histoire 135 (1853): 36–256, at 39.

[2] Thevet, Cosmographie Universelle, Vol. 2, 21.2, ff. 908v–909r.

[3] Émile Raunié, Épitaphier du vieux Paris, recueil général des inscriptions funéraires des églises, couvents, collèges, hospices, cimetières et charniers, depuis le moyen âge jusqu’à la fin du XVIIIe siècle. Vol. 1–3, Paris : 1890-1901), 302, n. 1171.