Living Memory – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

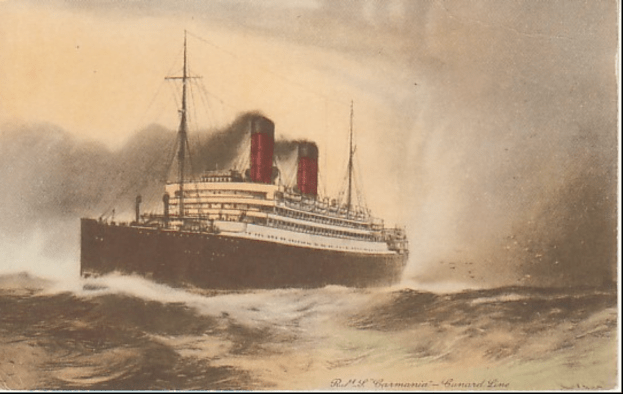

The Header Image on this Week’s Post is of the RMS Carmania, which carried my great-grandfather to America in April 1914.

A few weeks ago, when I visited Mount Carmel Bluffs and the Motherhouse of the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary (known more commonly as the BVMs) in Dubuque, Iowa I was struck at how even though it had been 8 years since my last visit and 14 years since the last time I was there for a family funeral, the memory of those relatives, my great-aunt Sr. Therese Kane in particular, still lived on in the sisters who came up to us throughout the day telling stories of times now long past and all the people they knew who lived in those moments. It had been so long since I’d seen Sr. Therese that it felt strange to still call her “Sister” as we all did in the Kane family when she lived.

That visit to Dubuque was in honor of Sister and my grandfather’s cousin, Sr. Mary Jo Keane, who died in April only a few weeks after having moved into her community’s retirement facility called Mount Carmel Bluffs. At her wake I noted to the attending sisters, relatives, and friends that she was one of the very last in my family who knew her parents’ generation who came to Chicago from County Mayo in the first half of the last century. Moreover, she was the very last person living who attended my great-grandfather Kane’s funeral in 1941, the last one who could tell some of the stories she heard as a child of life in Mayo at the end of centuries of colonial rule.

At Sister’s funeral lunch in 2009 I remember hearing Sr. Mary Jo, my grandfather, and their cousin Fr. Bill McNulty telling these stories about their parents, some of which I had never heard before then, of how hard it was for them to come to America, and of the trouble they faced in Ireland that led to their immigration. Some of these stories were still in the air at Sr. Mary Jo’s funeral lunch, told by my cousin Rosemary, yet as that first generation born in America leaves us so too their stories begin to fade away.

In the last week I slowly began to acknowledge the news of the lost submersible Titan which left St. John’s in Newfoundland for the wreck of the RMS Titanic and upon its descent beneath the surface was never seen again. At first, I acknowledged it was happening yet didn’t pay the story much heed, yet as my parents began to give it more attention and talk about it over dinner, I slowly started paying attention more. The Titan‘s mission to take tourists down to the remains of the Titanic 2.5 miles (3.8 km) beneath the surface of the North Atlantic is as much an act of nostalgia as any pilgrimage or historical tour can be. For $250,000 passengers were brought to the ocean floor to see the great ship as it rests slowly decaying away with the passage of time. I’ll admit the idea of seeing it for myself is intriguing, though even before the Titan was reported lost at sea, I doubt I’d ever take that opportunity to visit the Titanic.

One disaster resulted from fascination in another disaster. The sinking of the Titanic is a curious event for me because it is just on the horizon of what I consider recent events to my own life. Many of the last survivors––who themselves were old enough to remember the event––died around the time I was born, 80 years after the ship sank into the cold North Atlantic. What’s more, the generation of young immigrants in their 20s and 30s who left Ireland for America at the time of its sinking included my Kane great-grandparents who arrived in this country in 1914 and 1920 respectively. The Titanic followed the same course that my great-grandfather’s ship the RMS Carmania sailed between Cobh (then called Queenstown) and New York two years later in April 1914, and there is a point in my mind where it’s clear that had circumstances been different, had he sailed at age 20 instead of age 22, he very well could’ve been on the Titanic.

It’s always been strange to me to talk with people for whom recent memory is far shorter. When I started teaching at Binghamton University I expected my students, all New Yorkers, would have more vivid memories of 9/11 or perhaps had families who were directly involved, yet these students could tell me little about it, saying they were either too young or had not been born yet when the attacks took place 22 years ago. I think to my own early childhood, to my understanding of world events as the happened right before my birth in December 1992, and I at least have known a fair deal about events like the 1992 Presidential Election or the Fall of the Soviet Union in August 1991 for most of my life. I thank an insatiable curiosity and old Saturday Night Live re-runs for much of what I know about those events. Still, for most of my childhood memories of people who lived in the nineteenth century persisted, and so for me my great-grandfather Thomas Kane, who died 51 years before I was born, feels today closer than might be expected of someone who was born 100 years before me.

On Monday night this week I found myself diving deep down rabbit holes reading about Titanic survivors. It’s rather morbid to say that someone’s sole distinction is that they’re the last Titanic survivor of a certain demographic, that’s certainly something I’d have trouble being proud of. My reading led me to the story of an Englishwoman named Millvina Dean, who was a 9-week old infant at the time of the sinking, who was on her way to Kansas City with her parents to start a new life here on the prairies.

The Washington Post reported in 1997 on the completion of her long voyage when “85 years after setting out for Kansas City” she finally arrived here to meet cousins long separated by the waters of the Atlantic. The article in question mentioned where her uncle who the Dean family was planning on staying with lived, on Harrison Street, leading me to old city directories to see where on Harrison. The most likely address is at the corner of Harrison St. and Armour Blvd. on the eastern side of Midtown near where many of my maternal Donnelly relatives lived in the 1910s. Ms. Dean herself died in May 2009, I remember reading about her death when it happened; and on the centenary of the sinking of the Titanic, I noticed the date come and go. There was a story that weekend on CBS This Morning, yet for me the main emotion was a strange feeling of an event which had always been there in the edge of memory of the people I knew fading ever further into the distance, less a lived event that my relatives read about in the papers when it happened and more a historical event.

In time all our lives will reach that threshold, our memories recorded will survive as relics of people, places, and moments long past, and those that were only spoken or thought yet never written down will fade away. There is so much I wish I knew about the immigrant generation in my family, I’ve seen pictures, heard stories, been told I look like my great-grandfather Kane in a striking way, yet beyond those things I’ve never really known them. We are fortunate in our time to have so many audio and video recordings of our world, to an extent that our memories will hopefully survive long after we are all gone. The democratization of these technologies is a gift, it means that when future generations want to yearn for the early 21st century they will have the cornucopia of our recorded memories to relive. For older generations, we are left with visions of the past defined by movies, talking and silent alike, which the New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd wrote about this week, her own father almost boarded the Titanic on his Atlantic Crossing from Ireland. Like the French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss seeking the most remote of peoples in Brazil, to get an idea of what first contact was like in 1500, we are left with less recognition of the spirit behind these historical events the further they move away from us, until in a tragic ending to our story they are ancient history to us.