Return to Normalcy – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

Over the last week, I’ve been thinking about the standards we define to cast a model of normality, or in an older term normalcy. This week then, I try to answer the question of what even is normal?

One of the great moments of realization in my life to date was when it occurred to me that everything we know exists in our minds in relation to other things, that is to say that nothing exists in true isolation. The solar eclipse I wrote about last week was phenomenal because it stood in sharp contrast to what we usually perceive as the Sun’s warmth, and a brightness which both ensures the longevity of life and can fry anything that stares at it for too long. So too, we recognize the people around us often in contrast to ourselves. Everyone else is different in the ways they walk, the ways they talk, the ways they think and feel. We are our own control in the great experiment of living our lives, the Sun around which all the planets of our solar system orbit.

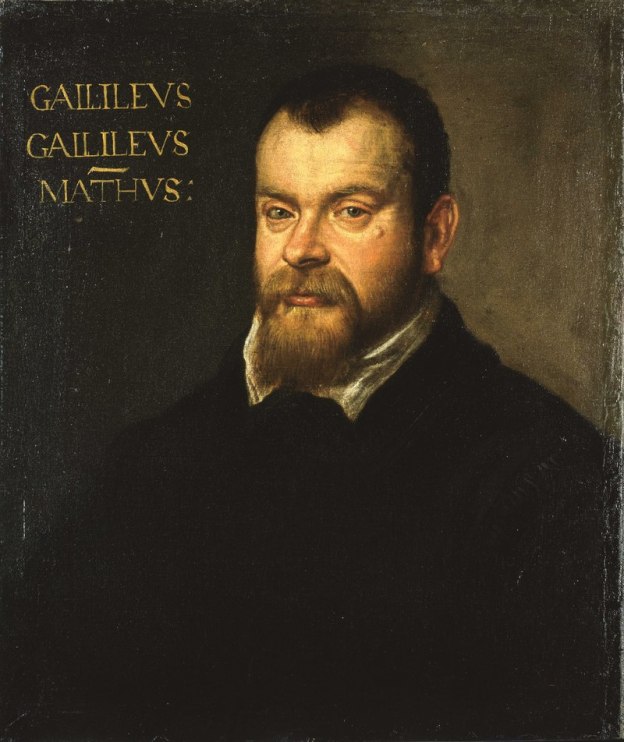

There is a great hubris in this realization, as a Jesuit ethics professor at Loyola said to my Mom’s class one day, in a story she often recounts, no one acts selflessly, there’s always a motive for the things we do. That motive seems to be in part driven by our desire to understand how different things work, how operations can function outside of the norm of our own preferences or how we would organize them. I might prefer to sort the books on my shelves by genre, subgenre, and then author; history would have its own shelf with the history of astronomy in its own quadrant of that shelf and Stillman Drake’s histories of Galileo set before David Wootton’s Galileo: Watcher of the Skies. Yet, at the same time I could choose to add another sublevel of organization where each author’s titles are displayed not alphabetically but by publication date. So, Stillman Drake’s Two New Sciences of 1974 would be placed before his 1978 book Galileo At Work.

This shelving example may seem minor, yet one can find greater divergence in book sorting than just these small changes here or there. My favorite London bookseller, Foyle’s on Charing Cross Road, was famous for many decades for the eccentricities of organizing the books on their shelves by genre, yet then not by author but by publisher. This way, all the black Penguin spines would be side-by-side, giving a uniform look to the shelves of that establishment. It is pleasant to go into Foyle’s today and see on the third floor all the volumes of Harvard’s Loeb Classical Library side-by-side with the Green Greek volumes contrasting with the Red Roman ones on the shelves below. Yet to have books organized by publisher when the average reader is more interested in searching for a particular author seems silly. Yet that was the norm in Foyle’s for a long time until the current ownership purchased the business.

Our normal is so remarkably defined by our lived world. In science fiction, bipedal aliens who have developed societies and civilizations are called humanoid, in a way which isn’t all that dissimilar from how the first generations of European explorers saw the native peoples of the Americas. André Thevet wrote in his Singularitez, the book which I’ve translated, that the best way he could understand the Tupinambá of Brazil was by comparing them to his own Gallic ancestors at the time of Caesar’s conquest of Gaul in the first century BCE. Even then, an older and far more ancient normal of a time when he perceived that his own people lived beyond civilization was needed to make sense of the Tupinambá. The norms of Thevet’s time, declarations of the savagery of those who he saw as less civilized for one, are today abnormal. Thus, our sense of normal changes with each generation. For all his faults and foibles, Thomas Jefferson got that right, in a September 1789 letter to James Madison, Jefferson argued that “by the law of nature, one generation is to another as one independent nation to another.” Thus, the norms of one generation will both build upon and reject those of their predecessors.

At the same time that we continue to refer to the aliens of fiction in contrast to ourselves, we have also developed systems of understanding the regulations of nature that build upon the natural world of our own planet. The Celsius scale of measuring temperatures is based on the freezing point of water. At the same time, the Fahrenheit scale which we still use in the United States was originally defined by its degrees, with 180 degrees separating the boiling (212ºF) and freezing points (32ºF) of water. the source of all life on our own planet and a necessary piece of the puzzle of finding life on other planets. I stress here that that water-based life would be Earthlike in nature, as it shares this same common trait as our own. So, again we’re seeing the possibility of other life in our own image. Celsius and Fahrenheit then are less practical as scales of measurement beyond the perceived normalcy of our own home planet. It would be akin to comparing the richness of the soils of Mars to those of Illinois or Kansas by taking a jar full of prairie dirt on a voyage to the Red Planet. To avoid this terrestrial bias in our measurements, scientists have worked to create a temperature scale which is divorced from our normalcy, the most famous of these is the Kelvin scale, devised by Lord Kelvin (1824–1907), a longtime Professor of Natural Philosophy at the University of Glasgow in Scotland. Kelvin’s scale is defined by measuring absolute 0. Today, the Celsius and Fahrenheit scales are both officially defined in the International System of Units by their relations to the Kelvin scale, while still calculating the freezing point of water as 0ºC or 32ºF.

In this sense, the only comparison that can be made between these scales comes through our knowledge of mathematics. Galileo wrote in his 1623 book Il Saggiatore, often translated as The Assayer, that nature, in Stillman Drake’s translation, “cannot be understood unless one first learns to comprehend the language and interpret the characters in which it is written. It is written in the language of mathematics, and its characters are triangles, circles, and other geometrical figures.”[1] I love how the question of interplanetary communication in science fiction between humanity and our visitors is often answered mathematically, like the prime numbers running through Carl Sagan’s Contact which tell the radio astronomers listening in that someone is really trying to talk to them from a distant solar system. There one aspect of our own normalcy can act as a bridge to another world’s normalcy, evoking a vision of a cosmic normal which explains the nature of things in a way that would have made Lucretius take note.

I regret that my own mathematical education is rather limited, though now in my 30s I feel less frustration toward the subject than I did in my teens. Around the time of the beginning of the pandemic, when I was flying between Kansas City and Binghamton and would run out of issues of the National Geographic and Smithsonian magazines to read, I would sit quietly and try to think through math problems in my mind. Often these would be questions of conversions from our U.S. standard units into their metric equivalents, equivalents which I might add are used to define those U.S. standard units. I’ve long tried to adopt the metric system myself, figuring it simply made more sense, and my own normal for thinking about units of measurement tends to be more metric than imperial. That is, I have an easier time imagining a centimeter than I do an inch. I was taught both systems in school, and perhaps the decimal ease of the metric system was better suited to me than the fractional conversions of U.S. Standard Units, also called Imperial Units for their erstwhile usage throughout the British Empire.

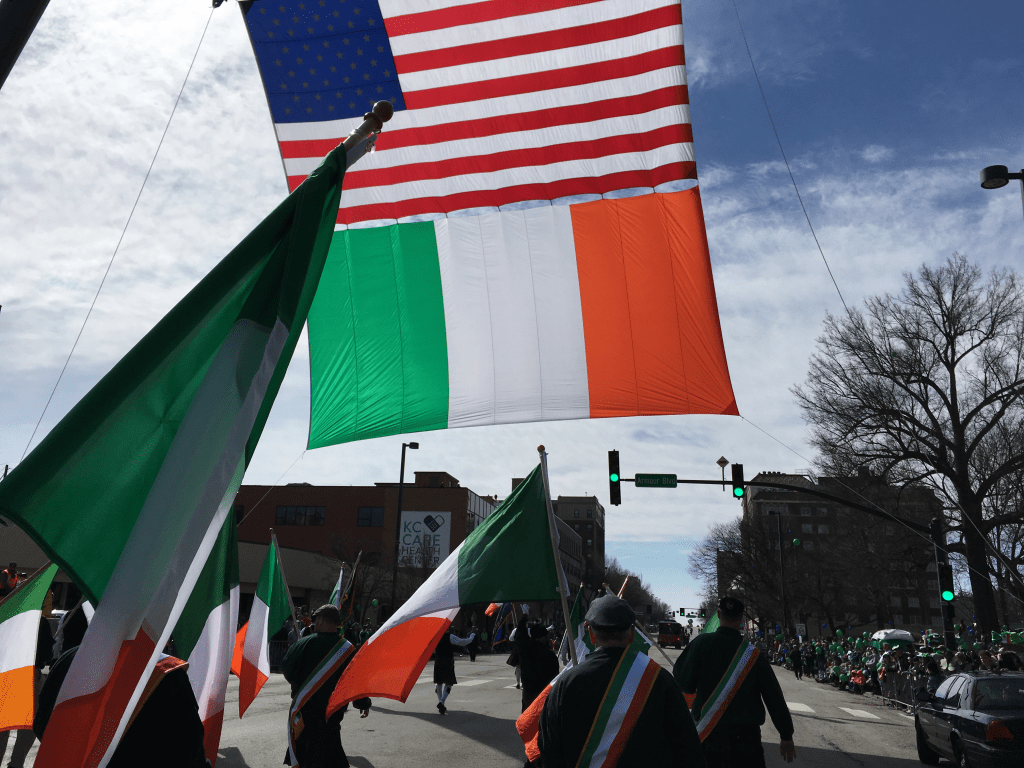

In his campaign for the Presidency in 1920, Republican Warren G. Harding used the slogan “Return to Normalcy.” Then and ever since, commentators have questioned what exactly Mr. Harding meant by normalcy. I think he meant he wanted to return this country to what life had been like before World War I, which we entered fashionably late. I think he also meant a return to a sort of societal values which were more familiar to the turn of the twentieth century, values perhaps better suited to the Gilded Age of the decades following the Civil War which in some respects were still present among his elite supporters. I remember laughing with the rest of the lecture hall at the presentation of this campaign slogan, what a silly idea it was to promise to return to an abstract concept that’s not easily definable. Yet, there is something comforting about the idea of there being a normal. I’ve looked for these normalcies in the world and seen some glimpses of it here or there. Perhaps by searching for what we perceive as normal, we are searching within our world for things we have crafted in our own image. We seek to carry on what we have long perceived as works of creation, the better to leave our own legacy for Jefferson’s future generations to use as foundations for their own normal.

[1] Galileo Galilei, Discoveries and Opinions of Galileo, (Garden City, NY: Doubleday Anchor Books, 1957), 238.