Inferno – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

A while ago, I began reading Dante’s Divine Comedy. So, over the next three weeks I will be writing my own reflections on each of its three parts. This week then, I begin with the Inferno.

Three years ago marked the 700th anniversary of the death of the great Italian poet Dante Alighieri, the author of the Divine Comedy, whose Tuscan dialect is widely regarded as foundational for the modern standardized Italian language taught today. I will write at length about language standardization in the future, if I haven’t already, yet today, dear Reader, I wish to address his Commedià itself. Around the time of his great anniversary, the Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies (CEMERS) at my university held a variety of lectures concerning Dante. In one such instance, I became critically self-aware of the fact that I was likely one of the few people in the room who had not read the work.

I finally got around to reading the Commedià in the last month when a new two-part documentary on the life of Dante aired on PBS. I realized then that even though I hadn’t read his magnum opus, I still knew a great deal about it because of how closely tied it is to my Catholic culture. The concepts of Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven as I grew up understanding them have clear support from Dante’s vision of these three realms. Yet like Dante, my own vision of these three is just as drawn from far older classical and biblical sources. He recognized the importance of connecting the beliefs of his own age with those that they replaced.

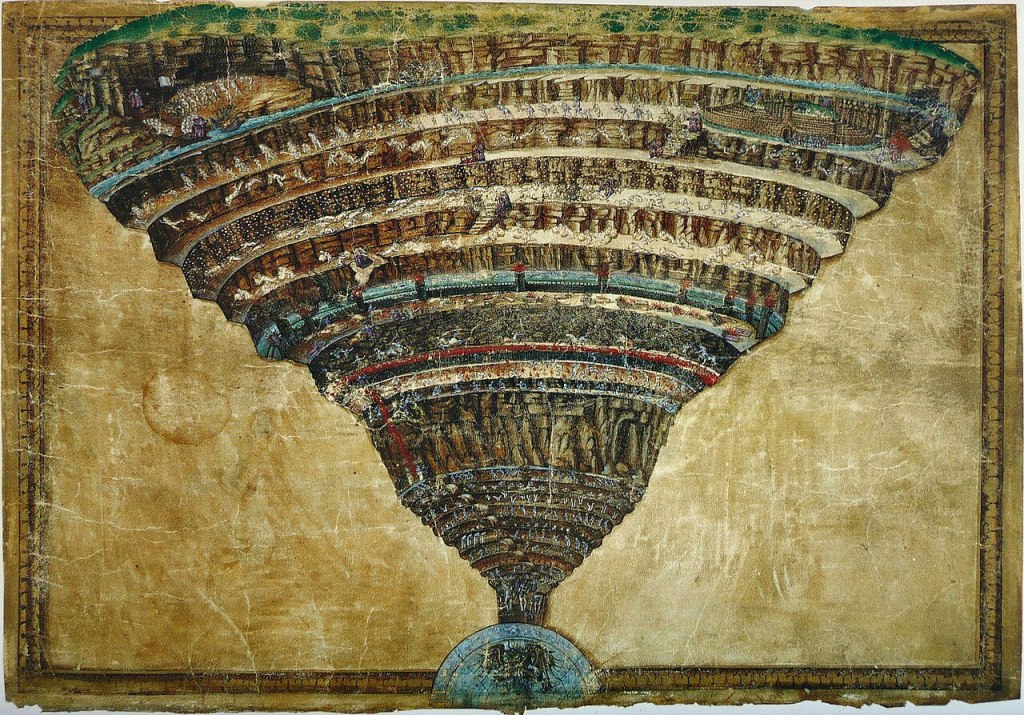

This is a point I made in conversation with a friend and fellow historian: Dante was a man of his own time. In his moment, it is fitting to see the great classical heroes, philosophers, and poets resting on the outer most layers of the Inferno because they had no introduction to God during their lives. Even more unsettling is his placement of the Prophet Muhammad within the eighth circle’s ninth bolgia as one of the “Sowers of discord.” Again, this fits in Dante’s own time and place, living at the same time as the Crusaders lost Acre in 1291, nine years before when the Commedià is set.

The Inferno is proof of four great truths which I wish to discuss in the remainder of this week’s post. The first of these is that faith often requires trust in more tangible things that one can see and touch and most importantly imagine. This past weekend on Trinity Sunday, I was moved by how my pastor––Fr. Jim Caime, SJ––described his relationship with the Trinity in his own prayer life. I believe in the Trinity, though what draws me towards that belief at this moment in my life is an appreciation for the mystery of the Trinity. It’s funny there, I appreciate the mystery of the most important doctrines of the faith yet when it comes to things that are more tradition than anything else, my faith is still built on a foundation that is strikingly tangible in its nature. At times I’ve thought that superstition might stick with me more because it’s something that is more tangible and everyday than some of the more metaphysical elements of my Catholic faith. Faith needs to be lived in “to live, thrive, and survive” in the words of the great Elwood Blues.

Second, I’m not a fan of iconoclasm. Culture is built by individuals yet adopted by communities. We live in a present moment which is layered upon the past. In those layers we can see bygone moments, years, decades, generations, centuries, millennia, and ages when our past thought something they made was worth cherishing even for a moment. Everything from the eternal grace of the great monuments of human endeavor, and our striving for greater truths is just as central to these ringed layers that form our culture as are the passing fads that come and go year by year. An article I read over the weekend in New York Magazine‘s style outlet The Cut about the millennial aesthetic that has defined the tastes of my generation in the last decade asked if “the tyranny of terrazzo” will ever end. The article concludes with a foreboding of the dominance of bright yellow among the style choices of our successors, Generation Z. I for one felt a similar sense of dread the last time I went clothes shopping at Target only to discover everything in the menswear section was geared to younger generations than my own. I continue to shop at Macy’s when I’ve gotten a nice paycheck and Costco when my parents are around with their membership.

If you’ll pardon that digression, the iconoclastic spirit would burn down the terrazzo of my generation’s invention and inspiration and would replace the soft hues with new and reactive bright colors. It would respond to decades of slow burning negotiation and working within the status quo with a fierce clamor to fight and resist even if the odds aren’t in your favor that your resistance will do you any good in the long run. I’ve been there and found that sort of thinking didn’t accomplish much and so settled for Dr. Franklin’s approach to change, make friends with as many people as possible and nudge them to do things you think important. In this light, my vote tends to be cast for more moderate candidates than my own views, and I’ll freely admit my own views on issues have changed with my own changing sense of frustration and irritation towards others whose voices are perhaps projected louder than necessary through social media.

So, I appreciate how Dante kept the voices and spirit of the pre-Christian past alive in his Inferno, that he was guided by the great poet Virgil, whose Aeneid I became quite familiar with in my senior year Latin IV class (Grātiās tibi agō, Bob Weinstein). It never seemed strange to my faith that the old faiths of Europe or any other religions could also exist within our understanding of Heaven, Hell, and all the rest. Again, Dante was a man of his time and his place, so to fit in the great heroes of Ancient Greece and Rome into his vision of the afterlife is only natural. Iconoclasm only harms us and our posterity by robbing all of us of the riches of our past and the finest parts of the great human inheritance. The iconoclast’s tradition to destroy what came before will only lead to their own destruction in turn by their posterity. Third, as powerful some may be in life it is the writers who will preserve their memories for eternity. Chaucer and Dante both preserved the memories of their enemies in a way that has led to the survival of those men’s names. Yet their names are not spoken kindly, so the world would do well to heed the power of the pen. They can live long beyond their memory ought to have otherwise. While more ancient stories began and lived for generations told orally and remembered from that recitation, we now in our learned state require things be written if they are to be remembered. In Shakespeare’s words, written for the Scottish King to utter upon news of his wife’s death:

She should have died hereafter;

There would have been a time for such a word.

— To-morrow, and to-morrow, and to-morrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day,

To the last syllable of recorded time;

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury

Signifying nothing. (Macbeth 5.5.17–28)

The writer helps human memory survive long after each generation is gone. Before our carbon dating or genetic coding of the remains of beings now dead, writing remains the original technology by which we recorded our nature and taught our learning, and dare I say our wisdom, to those who come after us.

Fourth, I admired how Dante cast himself as both observer and listener to the plight of the damned. In every circle he chose to stop and ask the souls he encountered their names and to tell him about their lives and why they were where they ended up. This more than anything else is a model we ought to emulate, as I’ve written before here, we ought to listen to each other more. I believe this would solve a fair number of the problems we face in our lives. Pope Francis’s message from the balcony after his election eleven years ago echoed this sentiment when he simply asked that we pray for him as he began this new ministry in his life. This is something that I want to get better at; I am so used to my own solitary company that I often have to consciously remind myself to make smaller gestures of gratitude toward the people around me.

Dante often offered to speak to the loved ones of those who he recognized on his journey through Hell or to pray for their souls. Yet where I saw the greatest pity was at the bottom circle when he beheld the three great traitors of his world being devoured by the heads of the Devil: Judas Iscariot, Brutus, and Cassius. After reading this Canto, I wondered if the Inferno were to be written by an American who might be our three great traitors? Yet here my own beliefs divert from Dante’s, as I find it distasteful to say with any authority what the spirituality of anyone else might be.

I recently finished listening to the most recent Star Was anthology book From a Certain Point of View: Return of the Jedi which is a collection of stories told from the perspectives of minor characters who appear in the film in question. One of the last stories was the main one I was looking forward to the most. It was from the eyes of Anakin Skywalker after his redemption from 23 years living under his evil alter ego as Darth Vader. What struck me here was that despite everything Anakin did in his life, the Force and his best friend Obi-Wan Kenobi, whose force ghost beckoned him into the next life, forgave him. I don’t claim to have any authority over whether one person or another ended their life in one state or another because of the power of forgiveness. Forgiveness is a deep expression of love that we ought to express and inhabit more. Forgiveness it isn’t something that necessarily came naturally. Most of the bullies I faced in my childhood got a silent response from me later in life. I’m not proud of how I’ve reacted to certain people and situations in a way that echoes my own fear and anger, because I know I can do better. Fear isolates us from love, after all.

As I continue reading, I’m eager to see how Dante grapples with forgiveness and with the love that fuels it. I for one am eager to climb from the depths of Hell alongside Dante and Virgil onto the slopes of Mount Purgatory, a cantica which I expect I might allow myself to read in my usual pre-bedtime hour. I chose to spare my dreams of the Inferno, figuring I give myself enough nightmares of my own invention as it is.

Next week then, I will write to you about the Purgatorio and Dante’s climb towards the climax of his literary life.