Historic Range – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

This week on the Wednesday Blog, why our conversations about ecology and culture are grounded in loss.

Over this past weekend I was in Denver for a cousin’s wedding, a joyous event on Sunday evening that was beautiful to be a part of. Besides the two evening events on Saturday and Sunday I had the weekend to myself to spend some time in one of my favorite cities in the United States. My first stop on Saturday morning then was to my old favorite Denver haunt, the Museum of Nature and Science in City Park. Longtime readers of the Wednesday Blog will remember this museum from my two-part post from the pre-podcast days of June 2021 titled “Sneezing Across the West,” in which I described my return to this museum as an adult 22 years after visiting as a young child.

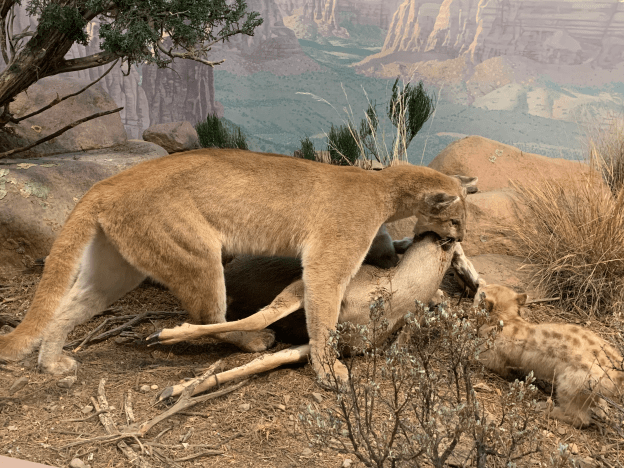

The Denver Museum of Nature and Science excels in its collection of dioramas, scenes from the natural world of taxidermied animals in their own habitats recreated in several halls on two floors for the public to experience a snapshot of wild life in its element. These dioramas capture my attention today far more than most paleontological exhibits, as while I enjoy seeing the dinosaurs and their fellow fossils, I’m now more drawn to the recreations of modern lifeforms, particularly mammals, that dioramas offer.

On this Saturday morning stroll through the museum, I stopped in front of a display of a puma, North America’s famed mountain lion, one of our more enigmatic megafaunal predators. I haven’t seen any mountain lions in the wild, though on one occasion a decade ago while hiking to a cave to shoot an ill-fated short film adaptation of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave in Pike National Forest I could swear our party was being watched from the ridgeline several hundred feet above us by a puma. I’ve only ever seen and encountered pumas in zoos and museums, behind wire fencing or glass. I got to know the resident puma in the Ross Park Zoo in Binghamton rather well, to the point that it would slow blink at me as I approached it, a sign among domestic cats of acceptance.

With my own limited experiences of pumas in the wild, it struck me to see the ubiquitous line on the diorama’s plaque which read “Historic Range” on the key to a map which showed how most of this continent was once puma country. I paused in my stroll at that point, and it occurred to me that our entire narrative of conservation and the preservation of human diversity in North America goes back at some point to a story of historic loss and the subsequent poverty for certain pieces in the continent’s ecology. For one thing, we lack large predators in much of North America west of the Rockies today, so especially in the great eastern woodlands the deer population is often higher than it ought to be.

Still, there is this core truth to our continental story, let alone the collective history of our hemisphere which tells of a black mark in our soil dividing the present age born in imperial colonialism and the time which came before. Like the K-T Boundary which can be seen in rock strata dividing the fossilized remains of creatures who lived at the time of the dinosaurs below in the Cretaceous Period and in the Tertiary Period after the asteroid impact which saw the demise of those reptiles 66 million years ago, this line demarcates a clear beginning of a modern world in the Americas warts and all. Before the arrival of Europeans into each distinct region of the Americas, each valley even, life on these continents developed in a very different manner, responding to circumstances which existed perfectly well without all the new flora, fauna, and bacteria which my European forebearers introduced after 1492.

I’ve always felt grief at the idea that so much of the life on these continents once flourished and now lies far diminished, shadows of their former selves. We could say that nature has been lost in the drive for conquest, to paraphrase a key point in Betty Meggers’s 1996 book Amazonia: Man and Culture in a Counterfeit Paradise, in our desire to realign nature around us to fit our own interests, we replace a tortured ecosystem with a corrupted egosystem which pales in comparison to its former glory. Nature is something we can try to control yet never fully overcome, for in spite of ourselves we remain a part of the natural world we seek to command to our will. Like Cnut in his greatest legend, we cannot command the tide to turn, nor can we even really ask, we can only observe and embrace the patterns of nature as they have developed over eons.

On Sunday, I turned from the beauty of the natural world to the beauty of the artistic world. That morning I paid my first visit to the Denver Art Museum, and was astounded by the seven stories of galleries, each designed around not only the art they contained but with strategically placed windows which opened the objects within to the cityscape and distant peaks of the Front Range and the Rocky Mountains beyond. I was most moved by the gallery containing art from the Old West, the period in my own home region’s history just before my ancestors arrived in places like Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Nebraska, and North Dakota at the turn of the last century. At the peak of what we call the Wild West, most of my ancestors who were living in the United States were farmers in Bureau County, Illinois, today located along Interstate 80 and the BNSF line that Amtrak’s Southwest Chief rolls along each day from Chicago to Los Angeles.

I grew up with a very romantic view of the Old West, of the cowboys and ranches, the wide open spaces of the prairies and the wild mountain landscapes of the Rockies which I visited as a child in the 1990s and early 2000s on annual summer trips to a dude ranch in Pike National Forest (the same property where I shot that film in 2013). Like many kids at that age, at the height of my love for the Old West, I wanted to be a cowboy paleontologist, pairing that historical fascination with my equally powerful love for dinosaurs. While I was in Binghamton, I enjoyed driving the 75 miles west to Corning, New York to visit the Rockwell Museum which specializes in this same American Western art, in order to get a taste there in the East not only of my childhood love for the West, but a sense of my own home region as it once was, a slight pill for my ever-present homesickness. Yet while the Rockwell Museum highlighted the effects of Manifest Destiny and westward expansion on the Native Americans and Mexican settlers who were already there, topics I’ve taught about in the U.S. History survey courses I’ve TAed before, it wasn’t until I wandered through that gallery on the 7th floor of the Denver Art Museum that I really began to understand how the romantic adventure stories of my childhood were also laments of the conquest of the world known and loved by the people who were already here.

On my way to Denver on Friday evening, I read a story in Smithsonian Magazine about the donation made by the Choctaw in the 1840s to help my own people, the Irish, during the Great Hunger caused by the potato blight that struck Europe at the time. I’d known about that donation for many years ever since I read about it in an Irish history book titled The Famine Ships when I was in middle school. Yet this article telling of two Choctaw students using an Irish Government program to travel to UC Cork to study and coming into direct contact with people whose lives and history were impacted by such unexpected generosity generations ago. My 3rd and 4th great grandfathers Keane were the ones who lived during An Gorta Mór, and on the Irish side of my mother’s family, my Irish 4th great grandparents came to America in the same decade after participating in the 1848 Young Irelander Rebellion. Like the Irish participants in the Smithsonian article, I too feel some of the kindness offered to my ancestors in one of their greatest times of need.

This empathy helps me to see less of the romance in the art from the Old West depicting the lonely native warrior standing proud and defiant against the conqueror, and more of the common cost of colonization which both my own ancestors in Ireland and the native peoples of these continents have faced down the generations. We all have our historic range, like the pumas in my life, we all have the limits to our modern lives cast in iron by the will of others seeking to control far further than their own borders. Denver today holds some of that Old West spirit that once defined it and Colorado at its core, yet the many voices which have written that city’s history and continue to define its present and future remain strong. In the Museum of Nature and Science I noticed how the remaining older exhibits were monolingual, with plaques written only in English, while all of the newer materials there and in the Art Museum are bilingual in English and Spanish.

We can learn from each other, and perhaps even restore some of the memory of our histories if we learn to listen to each other speak in our own words. The relationships we have with our relatives, friends, and neighbors alike will change with time, yet it is up to us what those changes will be.