Electronic Signals – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

This week, the coalescence of my thoughts over the last few months about how the way we communicate today in 2025 is so rooted in our technology.

For most of my life I tended to write a lot of ordinary quotidian things out by hand on paper either in notebooks, on notepads, or on the backs of receipts, envelopes, or whatever paper I had around. I kept up a good cursive hand and used it on a regular basis. Yet in the last decade technology has caught up to the humble notepad; a decade ago when I was living in London and trying to write out ideas for my first round of graduate essays on my phone’s Notes app while I was on the train or walking about, I often found that app in particular drained my phone’s battery at a considerable and worrisome rate. Then again, that particular smartphone tended to die if the battery dropped below 40 percent, so it had a bad battery. Still, that led to me continuing with the practice of keeping notes and scribblings in little notebooks or on notepads that I carried with me in a pocket.

It’s funny then that it’s only now in 2025 that I notice how little I write these same notes anymore by hand; in 2021 when my Mom came to visit me in Binghamton, she brought me a couple of notebooks emblazoned with pictures of various national parks on their covers, a new trend in notebooks that began around then. I was a little taken aback by this gift because by that point I’d largely done away with handwritten notes all together. In fact, my Binghamton years launched me head-first into doing as much as possible on the computer so that I’d have less paper and books to carry back and forth between Upstate New York and Kansas City. Like printed books over digital ones, when I returned to Kansas City I began to write handwritten notes again. This is largely thanks to my employers at the Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts; in our department we still carry around paper performance notes on our shifts. When I started, I was surprised to realize that at some point in the last 5 years I’d stopped carrying a pen with me on a daily basis. Since then, in April 2023, I’ve always had a pen in my pocket.

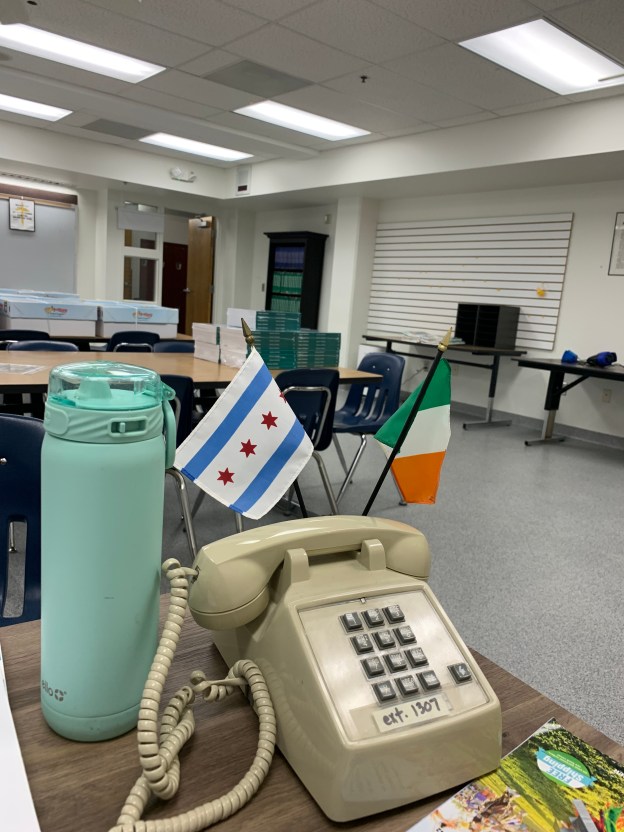

The pandemic reinforced our digital communications in ways which pushed us firmly forward toward more frequent videocalls and texting to the detriment of the telephone in particular. Most of my friends and family tend to prefer text messages over phone calls, especially among my fellow millennials, to the point that I often second-guess myself as to whether I should try calling someone in the first place. Is a phone call intrusive, whereas a text message is like a telegram or a letter? It can be replied to in the recipient’s own time, though with a text the response time is usually expected to be faster than with a letter that’ll take days to arrive, or even an email, which I see as slightly more formal. Since the invention of Samuel Morse’s electrical telegraph in 1838, our communications have moved into a realm of electricity which was foreign to our conversations and our lives beyond lightning strikes and the daily shocks one gets in a dry climate.

This Spring then, when I was regularly on videocalls–usually over Zoom–with friends, colleagues, and family alike a thought occurred to me that all of our communications are being translated down to electrical signals being sent over wires from one person’s device to another. Those messages, no matter the content, all buzz and fizzle through our wireless data signals and across our telephone wires, through our data centers and bouncing off our satellites all to better communicate to anyone whether on the planet or high above us in orbit or beyond. It’s made us all so much closer to one another. Today, I’m regularly in contact with people in North America, Europe, and Asia and that contact is often almost as instantaneous as if we were together in the same room. It’s what makes my solitary life feel lived in community with the people I like. And yet it’s also spoiled us for the slower communication of the written letter or even the face-to-face conversation that started all these “words, words, words” as Hamlet says that we “might unpack my heart with words.” We communicate to do just that: to speak our thoughts and to live in the strange and beautiful worlds we build around ourselves. So often now, those conversations are not only occurring with the aid of the electrical signals pulsing about our minds telling us how to react and what to say and do, but also through their extracorporeal currents which connect us through our technology across vast distances to one another.

You are listening to my voice filtered by the microphone and my audio editing software being transmitted to anyone with an internet connection. While naturally we aren’t supposed to hear it, as my hearing isn’t quite as good as it should be, I can now hear the differences between sound frequencies in a finer detail yet to the point that if two voices are speaking with the same frequency, I only hear ringing at that frequency and no words or other noise. This was demonstrated to me with dramatic and terrifying effect several years ago when I was nearly t-boned by a Kansas City fire engine roaring along at full speed because I didn’t hear its siren, which wails at the same frequency as the particular section of the 1st movement of Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto that I was listening to in my car at the time. So, when you hear my voice what you’re hearing is an electronic recording of my voice being transmitted to you. Often, I sound higher pitched on the recording even by just a half-step, than I do to my ears when I’m doing the recording. I’m a tenor, so I’m okay with that. Still, it’s noticeable especially if I record later in the day or at night, or if I’m nervous.

After I began my graduate studies in History back in August 2017, I started making a practice of recording any conference presentation or invited lecture I gave. I’d usually only make a sound recording, not wanting to deal with a camera. This way too, if someone missed a talk and wanted to see it, I could lay the slides over the recording in iMovie and turn it into a video to send around. This has turned into a wonderful tool for listening to changes in my voice over the years. Yet it’s also interesting now because I not only use this tool for recording the actual performance but also the rehearsals as well, and sometimes when I’m editing papers. I gave a lightning talk last week that was part of a webinar hosted by the Graduate Student Advisory Committee of the Renaissance Society of America about animal intelligence titled “Animals Adapting to Changes in Nature: Perceptions of Animal Intelligence in the Renaissance?” The paper itself was pretty quick and easy to write; it maybe took me an hour to make the first draft several months ago. Yet I began recording rehearsals and making edits after each one up to the minutes before I went live on Thursday morning. I was a bit nervous when I presented, so in the end the cool and practiced pace I’d planned with a mid-range voice ended up being a minute faster than expected and closer to my upper register. When I’ve thought about what to do if anyone asked to hear this talk after the fact, I’ve considered possibly sending out my last rehearsal recording from an hour before the performance, after all many speakers would in decades past make a separate recording of their lectures & speeches from the actual live reading. Yet to keep it authentic to the talk as it went ahead, I also feel inclined to send out the one that I gave on Thursday morning to the 16 other panelists and organizers on the call and the 35 attendees listening in from around the globe. This question gets to the heart of my talk because I made the case that André Thevet’s sloth showed signs of intelligence by refusing food it didn’t want to eat and not falling to the same bad practices as the Frenchmen who captured it or the native Tupinambá who were more familiar with it. Those practices, human faults one might say, include indecision.

Rather than flip a coin or pick another method of choosing, I’m instead going to play for you now the last rehearsal recording for one very simple reason. The main benefit of my recording of the actual talk is that it ought to have captured the organizer’s introduction and the questions that followed my presentation. Yet, my phone’s microphone couldn’t pick any of that up because my computer’s sound output was going into my headphones. So, without any more gilding the lily here are my thoughts on Renaissance sloths adapting to changes in nature, brought to you through a most electronic form of communication.

~

Animals Adapting to Changes in Nature:

Perceptions of Animal Intelligence in the Renaissance?

I want to begin by thanking the members of the RSA Graduate Student Advisory Committee for holding these lightning talks and accepting my proposal among the speakers today. When considering this question of animal intelligence, I’m drawn back to the Aristotelian notions of the animal sensitive soul in contrast to the human rational soul; Erica Fudge put it well, writing that animals can feel, perceive, and move, yet humans are the only natural beings to express intellect.[1] Animals were used as stand-ins for humans in allegory and vivisection, and an over-exertion of passion could drive a human into a state of animality, yet the human was understood to be fundamentally different because of our facilities of reason developed through experience over one’s lifetime.[2]

Newly encountered American animals played a disruptive role in this dynamic. Anatomically, many such animals defied European expectations for their size, or their chimerical character appearing as a composite of unrelated creatures known to exist in the wider Mediterranean World. Chief among these in my research is the three-toed sloth which was described by the French cosmographer André Thevet (1516–1590) in his 1557 book Les Singularitez de la France Antarctique. There are many different aspects of Thevet’s sloth which allowed it to stand out as a singularity among singularities from its appearance as a bear-like ape to its vocalizations “sighing like a little child afflicted with sorrow” to its general disregard by the indigenous Tupinambá people who explained aspects of its manner to Thevet.[3] I’ve written and spoken extensively about this, I know several of you have heard me talk about Thevet’s sloth at a number of conferences in the last several years. Today though, I want to discuss something I haven’t addressed yet in all these presentations; namely the signs in Thevet’s text which point toward some sense of the sloth’s intelligence.

The sloth’s intelligence is seen in its abstention from eating the food Thevet provided it. Thevet wrote “I kept it well for a space of 26 days, where I knew that it never ate or drank, but was always in a similar state.”[4] This reaffirmed Thevet’s assertion that “this beast has never been seen to eat by a living human,” either by the Tupinambá or the French.[5] This abstention from eating could well be understood as a sign of the sloth’s lack of a rational soul which would know to eat; yet I think it is better to perceive the sloth’s abstinence as an active choice made by an animal who didn’t favor the food it was offered. Thevet wrote that “some believe that this beast lives solely on leaves of a tree named in [the Tupi language] Amahut,” which is one of the Cercopia species known to live along the Brazilian coast.[6] Yet a 2021 sloth behavioral study published in the journal Austral Ecology has proven that this claim is less grounded in the genus’s actual experience.[7]

Perhaps the sloth can be best contrasted with the dogs which killed it at the end of that 26-day captivity, or even with the accused descent from humanity by first the Tupinambá and later the French in accusations of cannibalism. Unlike the humans who occupy these stories from France Antarctique who so often fall so far from their rationality to eat each other, the sloth simply refused to eat at all. This small creature, taken from its forest home and left in the care of an unfamiliar human who didn’t know what to feed it, chose to preserve its nature and not eat what was foreign to it. The sloth adapted to changes in the nature around it and expressed an intelligence perhaps more elevated than the humans who captured it. I’m drawn to one of the most poignant lines in Montaigne’s essay “Des cannibales” in which the erstwhile political animal himself wrote “I think there is more barbarity in eating a man alive than in eating him dead; and in tearing by tortures and the rack a body still full of feeling.”[8] In all of the variations on his sloth account, Thevet published this same story twice first in the Singularitez of 1557 and later in the Cosmographie Universelle of 1575, the dominant sense I get from Thevet’s text is one of befuddlement at an animal that defied his expectations in so many ways. In the tradition of animal allegories from Aesop to Renyard the Fox the sloth fills the role of an exotic oddity, a stranger in the canon of European natural history which didn’t quite fit any mold available. Even after Thevet’s sloth was christened by Conrad Gessner an Arctopithecus in 1560 and by Carolus Clusius as an Ignavus in 1605, this fact that it refused to eat or drink what Thevet offered it for 26 days remained a constant in its story. I see in the sloth a sign of intelligence beyond expected human norms and rules which rendered it exceptional. Any assimilation of the sloth was an artifice laid over its character, a colonial imposition. Still, its abstinence fit the framework of the sensitive soul, reflecting a delicate sensitivity toward things it found unfamiliar.

~

How does a 450 year old sloth’s intelligence have any bearing on the electronic signals which carry our communications in this new century? I wouldn’t have been able to study Thevet’s sloth in the way I have without the internet and all our technology. So much of my work is with digitized primary sources, mostly printed books, that I do almost all of my research on the computer. It’s a rare occurrence that I get to go into an archive to look at a source in the flesh. Yet I think there’s another interpretation we can take here: like the sloth we choose how much we are in touch with each other, how much of our lives are spent with our phones in our hands. My weekly screen-time report tends to fall in the 3 hour range per day. Yet I’m not only checking my social media accounts or texting with people on my phone, but I’m also reading books and writing notes and ideas down on my phone or using the camera to try and capture an artful reflection of the lived world around me. Recently on Instagram I saw another person’s screen-time report say they spend 14 hours on their phone per day, which is essentially the entirety of my waking hours. To me that is unhealthy to an extreme. Yet that’s how that individual has chosen to live their life.

I know that no matter where I end up, I will remain connected to others through our technology. Somedays I do miss the slower pace of sending letters or calling family and friends on the phone as things were when I was a child. I’d rather talk with someone face-to-face or voice-to-voice than text. As I wrote in January, I feel that we’ve allowed texting to take the place that videocalls were supposed to hold in the 21st century. We’re not constantly talking to people over monitors beyond Zoom calls that are scheduled and with that pre-arrangement more formal than the quotidian string of text messages. Today, I do have a notepad on my desk, one that was given to me among the materials of a workshop I attended at the École des Hautes-Études en Sciences Sociales in Paris last summer. It’s gotten some use, yet one year later I’m still only halfway through the gridded pages. As with so much of life in general, I feel that I’m trying to find a balance between the digital and the manual, between life online and life in this place where I find myself in a given moment. All I know for certain is that over all else, I long for connection.

[1] Erica Fudge, Brutal Reasoning: Animals, Rationality, and Humanity in Early Modern England, (Cornell University Press, 2019), 13.

[2] Fudge, 17.

[3] Thevet, Singularitez (Antwerp, 1558), 99r.

[4] Thevet, Singularitez (Antwerp, 1558), 99v–98r.

[5] Thevet, Singularitez (Antwerp, 1558), 99v.

[6] Thevet, Singularitez (Antwerp, 1558), 98r.

[7] Gastón Andrés Fernandez Giné, Gastón Andrés, Laila Santim Mureb, and Camila Righetto Cassano, “Feeding ecology of the maned sloth (Bradypus torquatus): Understanding diet composition and preferences, and prospects for future studies,” Austral Ecology 47 (2022): pp. 1124–1135, at p. 1132.

[8] Michel de Montaigne, “Of Cannibals,” in The Complete Essays of Montaigne, trans. Donald M. Frame, (Stanford University Press, 1965), 155.