On Vanity – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

This week, I reflect on the role of love in balancing between self-praise and community in a discussion of vanity.

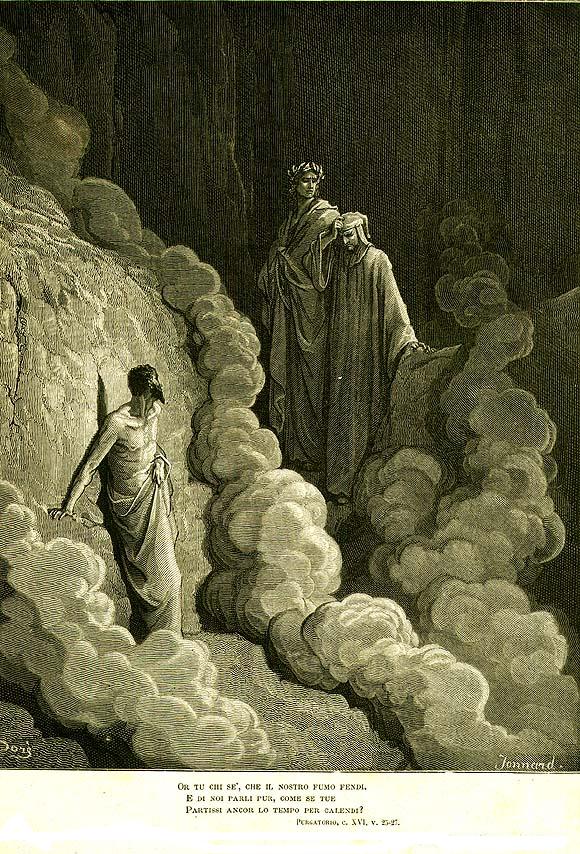

Today, in Rome the College of Cardinals will convene for the new conclave to elect our next Pope. By the time you read this we may have already seen white smoke rise from the chimney and met our new pontiff by his papal name on the balcony of St. Peter’s. Or more likely when you read this the cardinals will be amid one volley or another of voting rounds and deliberating their right course of action. Since the death of Pope Francis, I’ve felt rebuffed by the electoral speculation over who will be the next pope; by and large I’ve avoided reading any of these articles or watching any of these analyses. On the one hand, in my lifetime these lists of papabili have often been wrong. Francis was an unexpected choice. Yet on the other hand I see a sense of vanity in all this speculation which seeks the political power of the Papacy while ignoring its pastoral nature. I’ve long heard that the eventual choice of Pope is supposed to be directed by the Holy Spirit, whispering perhaps into the ears of the men in red like God did to Elijah in the cave. In my own experience, I’ve seen this most in the realization that the best path for me to take often is the strangest or most winding in character.

It takes a great deal of humility to take that particularly uncertain way in life, to not know where you’re going to end up. You have to learn to trust in yourself and in the people around you to make that path work. I’ve learned to expect things to break, and nothing that I try to work, and to figure out how to move forward in spite of what I’d dreamed and hoped for. I try to learn from my experience even when it is painful or heart wrenching to see dreams vanish and new realities, perhaps less glowing than what I hoped for, take their place. Still, the best way in my experience is to be patient and let things grow naturally around you and within you. The initial instinct isn’t always accurate, yet it should not be discounted either. There are days when the useless is best just to let your mind rest and decide where to go next. The late Renaissance French humanist essayist Michel de Montaigne (he actually wrote “I am no philosopher”) wrote in his essay “Of Vanity” of the men of his own time when France was wracked by forty years of civil war, “a time when it is so common to do evil, it is practically praiseworthy to do what is merely useless.”[1] I am often focused on resolving questions by finding immediate solutions, even if they are smaller steps leading to a greater whole. Yet in recent weeks I’ve found those solutions aren’t always needed or warranted, for they can sift the complexities of a problem so far down that the problem itself slips through the strainer and remains unresolved.

I recognize a degree of vanity here; I figure I have a strong mind and being reasonably well educated that I can attend to any problem and find a logical solution. Yet logic cannot account for humanity in all our chaos and charm. The character and nature of humanity is to spy ourselves in the glass and be marveled by it. We can be so caught in imagining our own glories and our own defeats that we miss the lived moments in between when we are surviving the daily fare and writing even the smallest of verses which will contribute to the song of our lives. I’ve learned to accept that my wishes for things are not always going to happen, and that as much as I warm my soul with dreams of wonders to come those dreams will only be realized by living with the people around me, learning about them, trying to understand them, supporting them, and appreciating them for who they are. Why enforce my own persuasions on you when I could appreciate you, dear Reader, for your own self and your cosmovision? This is a word I only recently learned, I saw it first in Surekha Davies’s new book Humans: A Monstrous History. It seems to originate in Spanish as a way of expressing the way in which reality is subjectively understood through our sensory perceptions. Descartes’s famous maxim for knowledge, “I think, therefore I am” means in this sense that we know what we know because we can perceive it. The cosmos in all its wonder is familiar to us through our sight, hearing, smell, and touch. I would much rather wait to hear your song and listen to it harmonize with mine than pull your voice into my own melody against its own nature.

Montaigne admired those in his generation who kept up the good nature of humanity, its customs, laws, and mores in spite of the world around them losing so much of that common purpose. In quoting Cicero, “not by the calculation of your income, but by your manner of living and your culture, is your wealth really to be reckoned,” the essayist speaks the greater value of a good life enriched by a passion for community and a charitable outlook on our pursuits.[2] While I’m a practicing Catholic, ever striving to be more faithful in my life, I firmly believe with my whole being that the state should be secular, the better to reflect the totality of the people from whom government derives its power. I would be vain to demand that the state reflect my Catholicism at the detriment of all my neighbors, even my fellow Catholics, whose faith is personal and distinct from my own. A good person recognizes this and seeks communion through mutual respect and appreciation. The most central tenant of my faith is that God is love, άγάπη, φιλία, and ἕρως alike in the original Greek, and the greatest expression of this love is in our liberty to make our own lives, our free will. If we are meant to live in this image then surely we ought to lower our pride and our vanity and hail the liberty of those around us to live their own lives and make their own choices?

For much of my life I’ve had a hard time taking criticism. I’m better at it today, yet it still is a something I know I will always need to work on. I’m no longer in a state of mind where I feel that I need to justify my actions or choices to everyone. On the inverse side, several years ago I finally caught myself trying to deflect praise with a witty quip that deflated some of the experience. This is something that I’d been doing for a long time perhaps to not inflate my ego too far. I went through my phase of wanting to be important, wanting to be a leader, and to be at the front of things and today when I am in that position in so many organizations, I’ve found that it’s much more fun to be a part of a team working together to achieve our common ends. Together these twin forces pull me toward a humility that I hope keeps me grounded, in which I’ve allowed myself to experience my successes while embracing the troubles that occurred in the course of those victories.

In my academic career I’ve published to date one public-facing article about my historical zoology research into the three-toed sloth and an encyclopedia entry titled “Amerindians in Brazil” for the volume South America: From European Contact to Independence which was published earlier this year. In both instances, I’ve since found things that I got wrong. It was a bit of a shock at first to realize this. In the case of the encyclopedia entry, I made a rather large error in misgendering a god, the Tupi deity Maire-Monan who I interpreted as feminine following the lead of the sixteenth-century Portuguese authorities, only to realize while I was writing a book chapter last summer about magic in Shakespeare’s play The Tempest the error I’d made. As such, the correction to the encyclopedia entry appears in the footnotes of that forthcoming chapter. Likewise, in the editing stage of a forthcoming article of mine, my first peer-reviewed article to be published, I was presented with conclusive evidence that my prior conclusions that the three-toed sloth found in my sources cannot be definitively identified as a southern maned sloth (Bradypus crinitus) as I’d written in that article “The ‘Sufficiently Strange’ Sloth” for EPOCH Magazine’s June 2024 issue but is in fact more likely either a northern maned sloth (B. torquatus) or a brown-throated sloth (B. variegatus). That prior assertion in favor of the southern maned sloth stands corrected now not only in my forthcoming article “A Sloth in the First French Colony in the Americas” but also in the latest draft of Chapter 3 of my dissertation.

A few years ago, I would have still had significant trouble accepting these critiques out of a strong sense of embarrassment at making such a mistake. In the case of the sloth’s historical zoology, I thought I read all there was to read about the different three-toed sloth species which live in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest, yet I was proven wrong by a generous reviewer who even offered a bibliography of where I could look to find more reliable information. Were, I always fixated on the looking glass of my successes I would surely miss the flaws that pronounce my humanity and not see the ample room for growth. I know that I’m not perfect, in fact I revel in the fact. And while my faith exists, I challenge anyone who claims to know definitive things about matters of belief whether they can really know the mind of God, a concept which as I wrote previously in my blog post from 12 March titled “The Divine Essence,” that divinity extends in scale far beyond human comprehension.

These last few years I’ve long felt a sense of disconnect between the two poles of my life. On the one hand in Binghamton, I felt a sense of professional accomplishment, I was at a good university conducting research and teaching, and a part of an academic community, however disparate that community was in practice. Yet I missed my family, I missed the Midwest, my home cities of Chicago and Kansas City became longed for isles of the blessed far to the west on the flatlands beyond the Appalachians. I longed to be active in my parish and to offer my talents to my brother Hibernians in elected office. I missed the regularity of the live music in Kansas City, the greater presence of the Kansas City Symphony in this city than anything I could find in Binghamton. Yet when I left Binghamton at a moment when I know I needed to leave, I found that I gave up more than I necessarily wanted. I lost that sense of professional accomplishment and surrounded myself by friends from beyond the academy who appreciate what I do but don’t necessarily understand the nuances of it. In the last few months, I’ve found something of that professional community through the learned societies that I’m a part of and at academic conferences where once again those two poles seem linked by a common axis. That axis is essential to a good life because it provides the balance which allows the individual to truly live to their fullest potential as a part of a wider community. I’ve known true solitude, a mantra of mine in recent weeks has been the simple Irish phrase, “Is mé i m’aonar,” or “I am alone.” It’s a plaintive call of sorts, yet it’s also a moment to learn from, that as much as I’m used to this existence that I want to grow out of it. Montaigne wrote in “Of Vanity” that “it is pitiful to be in a place where everything you see involves and concerns you.”[3] This is the solitary life, a life where about you all things revolve, and what’s worst about it is that it can be lived in community. Alone together was a phrase I read time and again during the recent pandemic. Yet even then with our need to stay apart we found ways to be together. I spent much of the pandemic years here in Kansas City rather than in Binghamton and still felt far more closely attuned to my professional community and the friends who populate it.

In these past few weeks, I’ve been happiest when I’ve had that connection with my family and friends, when I’m with other people and experiencing their lives, their passions, their perceptions of our shared world. I put faith in the currency of human connection and community because that is the most valuable coinage I’ve yet seen. All the gold and silver that humanity has ever mined cannot compare with the value of community and the humility it brings out in all of us. I have many highly accomplished, brilliant friends, and I’m delighted to count myself among them. There is some vanity in these friendships, after all we approach each other with our own experiences and stories to share, highlighting the things we’ve done, yet in a good relationship we do so to elevate our friends and encourage them to seek greater things for themselves. I feel fortunate to have met these friends, and to be able to put my talents to use serving our common cause.This week then as the cardinals vote in Rome, I hope they will look not just to their own personal interests, theological bent, or political persuasion. I pray they will listen for that suggestion that seems just strange enough that it could be right, and that they chose a Pope to lead our Church who will continue to build bridges that may close the divides erected for millennia between ourselves and so many of our fellows. I hope for a pope who will be a friend to all, a good diplomat who can unite disparate peoples together into one common cause. May his humility guide him to be the pope we need now in the second quarter of the twenty-first century, and when he is elected may we rise to the occasion to better ourselves.

[1] Michel de Montaigne, The Complete Essays of Montaigne, trans. Donald M. Frame, (Stanford University Press, 1965), 3.9., p. 722.

[2] Montaigne, Essays 3.9., p. 724.

[3] Montaigne, Essays 3.9., pp. 725–26.