This week, we join a team of federal agents as they investigate a strange museum owned by a reclusive Captain of Industry that has never opened its doors to the public.

Part I.

I arrived at Carruthers Smith’s Museum just after 4:15 in the afternoon after nearly a three hour drive out from D.C. and across the Chesapeake Bridge and most of Delmarva to Lewes, Delaware where the reclusive tycoon had taken up residence nearly fifty years before. My office began tracking his investments five years ago, when my colleague Bill Hardy was on the case, but just last week when he came out here to this beach town he never returned. My partner, Penny Wilson, joked when we were leaving the Hoover Building’s garage that Bill must’ve gotten distracted by the beach and stuck around for an unannounced vacation. Whatever the case, Smith’s file was dropped on my desk, and I was sent out to the Delaware Shore to see what became of Bill, and then to pick up where he left off investigating Smith’s Museum. There was something that didn’t make sense about a museum that had never opened to the public.

Carruthers Smith was one of the titans of the rubber industry, his tires and tank treads had helped us win the War in Europe, for one, and he was lauded by every administration since Franklin D. Roosevelt for his service to our country as one of the good, charitable captains of industry. His father was a strong supporter of the Taft Administration, having had his wings clipped by Theodore Roosevelt’s trust busting, and his grandfather one of the great Wall Street investors that supported Republican nominees from Grant through McKinley. The Smith Company hadn’t started with rubber tires, first they were a shipping company that cornered the market for trade between Rio de Janeiro and New York. They even helped keep an eye on ex-Confederates who’d escaped to Brazil in 1865, reporting on their whereabouts to Union authorities. Thanks to their deep connections in Rio as well as New York, they were well placed to corner the developing rubber market when it appeared almost forty years before Carruthers Smith was born. All this is to say it took a lot for any federal agency to be willing to investigate a good tycoon when there were plenty of rotten ones out there who ignored their workers’ safety or were notorious union-busters or preferred to outsource their factories overseas and flood the American market with cheap goods that were easily breakable and commonly known among the public as generally worthless. Smith Tires were different, they were sturdy and dependable, far more so than any competitor. They were especially good traveling over sand, so much so that the Army still kept a contract with Smith for tires for any future desert operations.

Still, Penny and I were there in front of Carruthers Smith Museum, our car parallel parked with the handbrake on Franklin Avenue. It was a very modern building, white walls that showed some of the characteristic curves of the Art Deco, yet it seemed less brutalist than the Hirshhorn and more akin in color to the Guggenheim in New York. There seemed to be no front door where you could queue to enter, but there was a smaller service door off Franklin Ave. that I could see from the driver’s seat. “Do you think that’s it, Pat?” Penny asked.

“Yeah, that seems to be it. Let’s go ring the bell.”

We got out of the car and walked into this small service driveway and up the five concrete steps that led to the service door. There was an industrial-type doorbell affixed to the wall at the top of the steps next to a door that on closer inspection turned out to be steel painted white to match the rest of the building, yet it had no window through which the respondent could see their visitors or vice versa. I rang the bell, holding down the button for a good two seconds. “Mr. Smith, this is Agents Patrick O’Malley and Penelope Wilson of the FBI, may we come in and talk to you?” We waited for another thirty before a buzzing announced to us that the metallic lock on the door was released, and we were allowed entry.

We found ourselves in a sort of room that could be a back office, it had denim blue carpet, and high wooden walls around which were photographs of the museum under construction beginning from the laying of the cornerstone in 1942. An old wooden desk stood to my left; it reminded me of a smaller version of the Resolute Desk that sits in the Oval Office. Before us was a set of stairs that led three steps up to another door. This one had a window, yet it was high up in the door, and thus too high for either of us to see through it. Yet there was light beyond it that seemed to dance off the high white ceilings of the room beyond. I nodded at Penny, and she walked up the steps and opened the door. The room beyond seemed minimalist in nature, yet it was still quite large. “This must be the museum,” Penny said.

“It looks that way,” I replied, scanning left and right as we entered the room beyond. There was a high angled white wall to our left in front of us, blocking our view beyond to whatever was to the south in that room. To our right the room continued for some uncertain distance, its white tile floors fading into the darkness at the far edge of the room. There didn’t seem to be any art on the walls of the museum, nothing here displayed. What could Carruthers Smith have been collecting these last 50 years? Beyond the angled wall in front of us light danced on the ceiling from something metallic. I proceeded cautiously, my gun still holstered, as was Penny’s, yet we both knew we could draw in 3 seconds at least and be on guard. The heavy sounds of our shoes clicked across the floor as we rounded the corner and found a small metallic box on a table in front of a large glass display case standing erect that housed a large rubber object, rectangular in shape, and standing at least 6 feet tall. It seemed taller being up on a podium. I looked up at it, confused what I was seeing, “maybe it’s the largest single piece of rubber the Smith Company has ever produced,” I quipped to Penny.

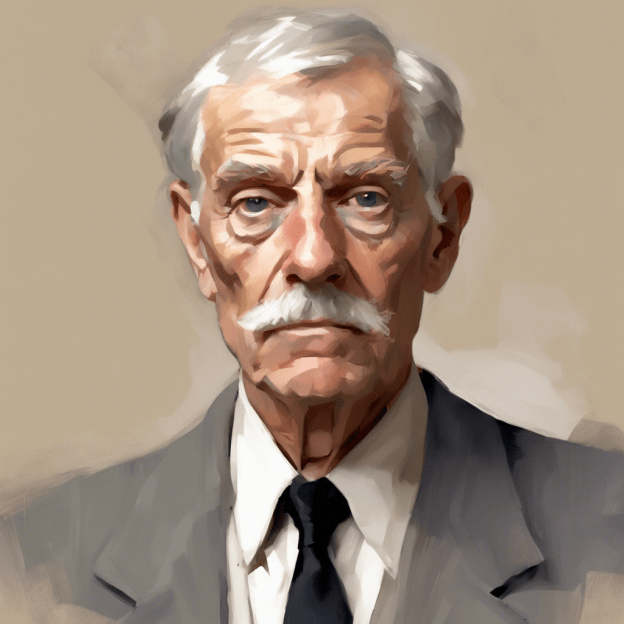

“It is in fact,” came a voice from behind us. We turned to see Carruthers Smith standing there, a tall man who once might have been the eye of many a high society debutante. He was slim in frame, wearing a gray double-breasted suit of the kind not often seen since the early 1960s. “This is the largest single piece of rubber that my family’s firm ever acquired and sought to study. How do you find it, Agent Wilson?”

Penny looked back at it, “it’s a little unsettling, how is it held up in the case?”

“You are welcome to walk around the back and discover that fact for yourself,” Carruthers replied in a slow, tenor voice that betrayed hints of the Transatlantic accent he and his class used decades ago.

Penny looked at me and I nodded approval, sending her around the case to its right to ascertain the supports for this piece of rubber. “How is it standing on its own?” she asked with incredulity seeping through their voice.

I walked left around the case and found her behind it looking for where some sort of supports ought to be yet instead there was nothing. The rubber artifact instead stood erect inside the case, not leaning on it or putting any pressure on the glass that could shatter it. Carruthers appeared behind Penny, “it truly is a wonderous specimen, one that was brought to our office in Rio from deep in the Amazon in 1941, on the same day that the Japanese attacked our fleet at Pearl Harbor. My agent who ran the Rio Office then, a Senhor Dos Santos, said that anyone who touched it felt as though they were touching something that seemed alive.”

“Alive?” I asked, quizzically raising an eyebrow.

“Yes, Agent O’Malley, this artifact was alive when it arrived here in early Spring 1942. I had it shipped into our wharves in Jersey City where it was loaded onto a train and brought to Lewes where I could study it myself.”

“Mr. Carruthers, I know your family’s connection to this town doesn’t go back very far, didn’t your father have a summer cottage here?”

“No, most of the family would summer in Newport, Rhode Island with our friends, yet I was the one who enjoyed the waters further south here in Delaware and found Lewes a fine enough little town to build my summer cottage here,” Carruthers replied, never dropping his hint of a smile.

“When did you first come here then?” Penny asked.

“In 1932, an 18 year old looking for something profound and reclusive in life. I’d read Thoreau you see; Walden inspired me to seek new things beyond the family firm or society life in New York. The Depression brought land prices low here, and I thought I might be able to help the local people. I provided tires at a 33% discount to all residents of Lewes, which ingratiated myself to their company.”

“Is that why you built this museum?” I asked.

Carruthers looked around him at the cavernous space, its white walls and white tile floors made the space feel monochromatic and minimalist. “I built this museum to house the treasures I’ve collected in my years, things old and new, mundane and,” he gestured to the rubber artifact before us, “wonderous.”

“But why haven’t you opened it to the public?” I asked, “Surely this would be a testament to your life and work like the Carnegie Museums in Pittsburgh or the Freer Gallery in Washington?”

“I never felt that it was complete and ready for the public. There was always something missing, something which I couldn’t quite place. I’ve been collecting for this museum now for 58 years ever since I first arrived in Lewes, and still the museum is not yet finished. But you, dear agents, have come a long way, surely you have business to attend to?”

I looked at Penny who nodded and walked back around the display case. We followed behind her to the metal table that stood beyond. “Mr. Smith,” she began, “we are here to ask two questions. An agent of ours, Bill Hardy, came here a week ago to inquire into the contents of this museum that has never opened and ensure they are all legally in the country, and he has yet to report back to the office since. So, we are here both to see if you know what might have happened to Agent Hardy and to complete his assignment.”

“I met with Agent Hardy when he arrived here on the 10th, he seemed to be in a hurry to return to Washington, so I didn’t want to detain him too long. As to his investigation into this museum, you can find the effects of that effort on the table here,” Carruthers motioned downwards toward the metal table between them where a single silver box was placed in the middle.

“Sir, are you here alone?” I asked.

“In fact, I have one assistant here with me,” Carruthers motioned to a man who only just seemed to appear from the corner of my eye. He wore a dark green museum guard’s uniform, with a black necktie on a white shirt. “Have you met Peter Dougherty? He’s one of your tribe, a fellow Irish American born in Brooklyn.”

I turned to see Peter more clearly and saw a wizened old man, at least 80, who looked back at me with tired eyes. “How long as Mr. Dougherty been working for you?” I asked.

“Peter was hired by my father as a warden to keep watch over me in my youth, in 1929 I believe.”

“That’s correct, Mr. Smith,” Peter replied in a low baritone voice.

“And you’ve been with Mr. Smith ever since?” Penny asked.

“That’s correct, Agent Wilson.”

“Peter served in the first war in the trenches under my Uncle George’s command, and after the war when lost his job after Black Tuesday, my dear uncle asked my father to bring him on.”

“So, this Peter has been working for the Smith Family for over 60 years,” I thought, “he’s loyal then, very loyal.” “Where did you serve, Mr. Dougherty?”

“At St. Mihiel and in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive with the Fighting 69th,” he replied proudly.

“We appreciate your service,” Penny smiled at him. Peter returned the smile, yet he seemed tired by the process.

“So, you say that this box is what remains of Agent Hardy’s investigation?” I asked.

“Yes, Peter collected the things he left here.”

“And when did he leave?”

“He left his investigation on the 10th,” Carruthers replied, his expression unchanging.

“On the same day he arrived?” Penny confirmed aloud.

“Indeed,” Carruthers affirmed.

“Then you haven’t seen him since the 10th?” I asked, pulling a notepad and pen out of my jacket’s right pocket and opening it to a page titled “Carruthers Smith Museum.”

“That is correct, he had a sudden change of mind and chose to end his investigation right here while he was looking over the financial records of my museum.”

“May we see those records?” I asked, trying to understand why Bill would give up an investigation like that.

“Certainly, Agent Wilson, will you follow Peter, he’s not as strong as he once was and could use the help lifting these boxes, unless you’d rather attend to it, Agent O’Malley.”

I looked at Penny who gave me a glance, I knew she could do this well enough, “Go with him, you’ve got this.”

“Understood,” she replied, before turning and following the aged soldier to the northeast across the large gallery in which we stood until they passed beyond the light and into a portion enveloped in darkness. I could still hear their footsteps as a door beyond sight opened and they passed through that portal to the collections’ storage beyond.

“How long have you and Agent Wilson been together?” Carruthers asked.

“She was assigned to be my partner fresh out of the academy two years ago.”

“So young,” he pined, “but keen eyed still. Would you care to sit and inspect the effects of Agent Hardy’s investigation,” Carruthers motioned toward the box on the table.

I sat, feeling as though the invitation was unavoidable and slid open the metal lid with my hands. Inside were several metal artifacts, a slide-rule, Hardy’s notepad, and a paper sheath for the instrument. I took the notepad out first, noting that it was closed and flipped open the cover. The first few pages were notes from other cases he’d worked recently, followed by a page with directions to Lewes from Washington. Yet after that the pages were just filled with what seemed like random numbers, ten full pages of random numbers. “Can you explain these numbers, Mr. Smith?”

Carruthers looked down at the paper in my hand, “they refer to specific indices in my records, you can find everything you need in the documents that Agent Wilson and Peter will shortly be bringing to this table.”

I looked back down at them, and began to mutter the numbers aloud, for no apparent reason, yet still to mutter them aloud all the same. “Seven, nine, six, five, three, one, nine, eight, two, five, three, one, eight, three, seven, six, nine, zero, seven, five, three, nine, zero, seven, two, one, six, five, three,” until I found my eyes drooping, an air of drowsiness coming over me. It seemed like a good long while since Penny and Peter had left my sight and gone into that distant room off in the dark, what could be taking them so long? “Seven, nine, six, five, three, one, nine, eight, two, five, three, one, eight, three, seven, six, nine,” I tried to stand from the table yet felt my body heavier than expected; it was a weight which felt less physical and more emotional. I could swear I saw the display case to my left open, how could that be opening?! The large rubber artifact was there before me, what a strange thing it was. I began to see the darkness consume the distant edges of my vision until all that remained was that artifact, which seemed to yawn before me. I thought I could hear Bill’s voice, “Pat! What are you doing?” but soon all was silent.

Part II.

Penny found the collections room to be far less impressive than the gallery beyond. It’s linoleum floors and light green walls seemed to be caught in a time loop going back to the late 1940s when this part of the museum was built. She followed Peter further and further back into the collections until they came to a locked metal cabinet on a nondescript back wall. Peter took a key from his coat and unlocked it, revealing nearly a century’s worth of documents behind the door. “This is everything,” he said, “everything from Mr. Smith and his father’s time leading the firm.”

“Mr. Smith’s father retired in 1936, yes?” Penny asked.

“Yes, he left the firm to Mr. Smith in that year.”

“And how long has Mr. Smith been collecting for this museum?”

“For as long as I’ve known him,” Peter replied.

“You know, my grandfather served in World War I,” Penny said, trying to make small talk as she began to finger through the files.

“Did he,” Peter seemed uninterested in the topic.

“Yes, he was an ambulance driver from Kansas City, most of the guys on his crew became animators.”

“We all have our own paths to take, Agent Wilson.”

Penny kept looking through the files, moving fast between folders with handwritten dates and names on them. “Are you looking for anything in particular, Agent Wilson?” Peter asked.

“Not yet just trying to get an idea of what’s in here,” she replied as she kept quickly flipping through the folders. “So then, if you won’t talk about the war, what did you do between then and when you started working for the Smith Family?”

“I was an interpreter for a while at Ellis Island until the government closed that facility in 1922.”

“Which languages do you speak?”

“English, French, Spanish, and Portuguese.”

“Oh wow, you’ve got a knack for language, then.”

“I ran away from home when I was fourteen and took a job on the Smith Company’s ships going to Rio, learned Portuguese there and Spanish on their stopovers in San Juan and Havana. I learned my French during the war. Captain Smith put me on interpreting duty with our French allies when he heard about my work.”

“That’s Mr. Smith’s Uncle George, right?”

“Right.”

“So, what’d you do after 1922, Mr. Dougherty?”

“I tried going back to the Smith Company, but they weren’t taking as many sailors for the Brazil Route anymore, so I became a policeman.”

“You were a cop?” Penny turned to look at Peter who stood behind her still looking as tired as before.

“I served with the New York Police Department for five years until 1927.”

“What happened then?”

“My sergeant had us raid the wrong alderman’s office and we were all out of a job.”

“That’s tough,” Penny paused a moment, “I’m glad you were a good cop. My dad is a cop in Kansas City, it runs in our family.”

Peter was silent, he still seemed reluctant to share much more than was necessary, even if it was just to pass the time.

Penny ignored this, “What about your personal life, did you ever marry?” she asked, trying to unlock the man behind her as she pried open the files before her.

Peter was silent for a moment before she heard a sigh, the first sound he’d made other than the odd monotone words she’d heard from him before. “I did, a long time ago.”

Penny smiled, “what was her name?”

“Delia McGinty.”

“I see you stayed in the community,” Peter made no response to that attempted joke. “How did you meet?”

“At a party in 1924 at the Hotel Commodore on 42nd Street in Manhattan hosted by one of the big Irish organizations in the city. She was there with a friend, Mary Mulroney. They were both famous for standing up for themselves.”

“What did they do?”

“They were suffragettes during the war, and afterwards Delia worked as a schoolteacher on the Lower East Side. She wanted to give these new kids who’d just arrived the welcome that our parents’ generation didn’t get.”

“She sounds like an amazing woman. So, what happened?”

Penny could feel a darkness shift over Peter’s face even though her back was turned to the older man, “We were married for nearly twenty years, but she disappeared around the time we went to war with Germany the second time in 1942.”

Penny turned and offered a compassionate look, “I’m sorry, Peter, that must have devastated you.”

Peter returned her gaze with a weary look, “It was a long time ago. My cop friends couldn’t find her, there was no sign of her anywhere. Mr. Smith took me in and invited me to move here to Lewes with him. I left the city and the memories and started anew.”

Penny had reached the bottom third of the files when she found one that caught her eye, she read the label, “1941,” and turned to Peter again, “Isn’t this the year that that rubber artifact came into the Smith Family’s possession?”

Peter’s face seemed weary, yet sharp with a renewed purpose. He reached into his coat pocket and drew a pistol, pointing it at Penny who stood from her squatted position. “Peter, what’re you doing?” Penny asked, alarm in her voice as she reached for her sidearm.

“Don’t move, Mr. Smith said no one is to inquire about the origins of the artifact.”

“Peter, you need to lower your weapon and put it on the floor,” Penny commanded.

“I work for Mr. Smith, not you,” Peter said with a cold steel in his voice.

“Mr. Smith is hiding something, Peter, why else would he order you to put your life and freedom in jeopardy by threatening a federal agent to protect it?”

Peter gave no answer, but his hand had begun to shake. Penny stepped forward, gingerly, eyes on Peter’s. “Peter, I’m not going to hurt you, just give me the gun. There’s a reasonable explanation for all this.”

Peter’s hand lost its steadiness, and Penny closed the gap between them, taking the gun from his hand and resetting the safety. She looked it over, “whose gun is this, Peter?”

“It’s my old service pistol, from my cop days.”

Penny looked at the gun, it had to be at least 63 years old, before returning her gaze to Peter, “let’s start over again,” she held the 1941 file up to him, “why is this file so important, Peter?” Peter was silent, “You were a good cop, remember, going after corrupt officials, protecting your community. Is it worth going to prison in your nineties to stay silent about this?”

“I’ve lived a long life,” Peter said slowly, “Mr. Smith is the only person I have left. You’ll get there someday, Agent Wilson, when everyone you’ve ever known is gone.”

“Yeah, you’re right, but for now Peter I’m with you, and I want you to understand I’m not going anywhere until you explain why you pulled your gun on me.”

“Mr. Smith said no one should ever know what that thing really is, what it does. It caused a big ruckus in Rio when they first brought it into the warehouse. He never said what happened, just that they had to handle a police investigation over it and that some workers died.”

“Some workers died because of that thing?” Penny was alarmed at the thought. “Pat’s in there, right next to it.”

She ran for the door, leaving Peter behind her, pulled it open and charged back toward the table where Carruthers stood. “Where’s Pat!” she shouted.

Carruthers turned to meet Penny’s fierce eyes, “Agent O’Malley left his investigation,” he said in the same soft, dry voice he’d used when they met him.

Penny looked at the display case, it wasn’t quite as she’d left it, instead the front plate of glass seemed to reflect the light just a bit differently. “Mr. Smith, when I collected this file from your cabinet, your man Peter pulled his gun on me. Would you care to explain?”

Carruthers looked to the file in her hand, “1941” he read on the label. “That file is confidential, and without a warrant I see no reason why you must be aware of its contents. Please return it to me,” he held out his hand.

“No.”

Carruthers’ face lost the soft glow of friendliness it’d had since they arrived, “I believe the law is clear on this matter, you have a piece of my personal property which if I’m correct in assuming you have no specific warrant to search.”

Penny opened the file, as the papers caught the light from above, yet at that moment Carruthers moved to slam it shut, “you will not read anything in that file, it is not yours to read!” he commanded.

“If you don’t want me reading that file then you can tell me where Pat is. When I left you, he was sitting at that table. You were the last person to see him and now he’s not here.”

“He needed a rest from his troubles.”

“What do you mean, rest?” Penny gave Carruthers an interrogatory look, her eyes locked on his. She caught the smallest of a micro expression, his eyes glanced slightly to the left toward the display case behind him. Penny dropped the file, revealing Peter’s service pistol in her hand beneath it, pulled the safety back and fired a shot into the display case. A second shot shattered the glass. A third pierced the rubber artifact within. An oil began to ooze out of the artifact as the air entered a newly formed chasm in the bullet’s path. Penny drew her own service weapon from the holster at her hip and pointed it at Carruthers. “Explain,” her one word command.

“You have no right,” he whispered in a seething, quiet, and deadly voice.

Footsteps came from behind as Peter appeared from the darkened far end of the gallery, a shocked look on his face. “Mr. Smith, I tried to stop her,” his voice faltered as he looked to the shattered display case and the fast liquifying rubber artifact. A hand appeared from within, followed by the arm to which it was attached, and soon Pat’s face and body were restored to light and air. Penny ran forward, her gun still drawn toward Carruthers. She pocketed Peter’s service weapon and caught Pat at his shoulder.

“Are you okay?” she asked.

Pat looked around, and caught Carruthers in his sight, “what was that thing?”

Yet before he could respond another body appeared from the case, someone who was placed below Pat, it was Bill Hardy. He hadn’t taken that unannounced beach vacation after all. Penny got Pat onto his feet and went to help Bill who’d been immobile for a week now. “That thing ate me!” Bill shouted; his eyes blurred by the sudden shock of the gallery’s artificial light.

There was still a good half of the artifact left, yet it kept draining out of the case, a white liquid oozing down onto the white tile floor below. Another figure began to appear, someone crouched down, kept still by the weight of the prison in which they’d been enthralled. Penny heard a sob come from across the room, and unsteady feet run forward as Peter approached the milky pool, “Delia?!” he shouted.

Peter saw as a frail woman appeared from within, she didn’t seem to have aged as much as would be expected. She was crouched over, in almost a fetal position, wearing the same blue dress she’d worn the last day he saw her. Her eyes were glazed over, surely, she hadn’t seen daylight in almost fifty years. Yet her hair still had mere whisps of gray. Peter helped her up, though unsteady he lifted her from what remained to the artifact and set her in a chair at the metal table. Ensuring she was safe, and wouldn’t fall from her chair, where she’d begun to rub her eyes, Peter turned to his employer. “What happened?”

Carruthers looked at the man who’d stood by his side for the last half century and laughed, a cruel, heartless laugh. “She came to me to ask about the workers who’d died in Rio. She said that she wouldn’t let it slide, and that if I was a true patriot, I would be better to my workers. Yet while we spoke, she saw the artifact, and slipped in.”

“I didn’t slip,” Delia spoke with a defiant voice. “You gave me a piece of paper with notes about the workers to read, you told me this would have all the information I needed. You said I should read it aloud to prove to me that what you read was the truth. I read it and was drawn into that monstrous thing of yours.”

“That’s what happened to me!” Pat shouted.

“You had me write those numbers in my notebook, I figured they were accounting figures,” Bill said groggily. “What do those numbers do?”

Carruthers remained defiant, keeping his silence in spite of his situation.

“Give it up, Carruthers, you’re done for,” Peter said, standing up to the man who’d commanded his loyalty.

“How dare you speak to me that way,” Carruthers seethed.

Peter raised himself before the man, “You’re no better than the rest of us, you and your captains of industry. You were born into riches, but do you really know what I had to do just to survive? I’ve been watching you for sixty-one years, I know who you really are you two-faced miser. You’d happily put on the red, white, and blue in support of the war effort and to make people feel proud to buy Smith, but any chance you got to denigrate Mr. Roosevelt or Mr. Truman you took. You’re one of the good bosses, that’s what you told everyone, but I know you for the weasel that you are, the wolf in sheep’s clothing. You don’t care for any of us, not a one. We could all be starving and dying of plague and all you’d do is pack up and leave us to die.”

Carruthers was seething with rage now, “How dare you speak to your betters like that, you worthless Irish scoundrel! All of you should’ve been sent back on your ships with your agitators and your freedom fighters! And you, Delia McGinty, we had a name for you and your kind who upset the natural order of things in 1920. Insufferables you all were!”

Penny stepped forward, “that’s enough of this,” she took a pair of handcuffs from her jacket pocket, “Carruthers Smith, you’re under arrest for kidnapping, and attempted murder.” She grabbed his wrists and placed them behind his back, cuffing him there. “Bill, do you want to help me get him to our car? This was your case first.”

“Gladly,” Bill said.

Pat turned to Peter, “do you have a phone? I should call the office for backup.”

Peter pointed toward the darkened portion of the gallery where he and Penny had disappeared before Pat began to read Bill’s notepad. Pat nodded and walked to the collections room to place his call.

Peter turned and looked back at Delia. He took the other chair at the table and brought it around to her side, sitting in it next to her. “Delia, do you remember me?”

“How long has it been, my love?”

“Forty-eight years, forty-eight long years,” he sobbed as he hugged her.

She looked at his face, “you must be at least ninety by now.”

“Yes, but you don’t look a day older than the last time I saw your face.”

“I don’t understand it,” she said, “if it’s been forty-eight years then I must be at least ninety-five. Do you have a mirror?”

Peter looked around and cautiously took a shard of glass from the floor and held it up for Delia to see her reflection. “How is this possible?”

They looked down at the floor, at the milky white liquid that oozed from the fallen artifact, gobsmacked at this new lease on their life together.

Part III.

The following morning a story appeared on the newswires in papers nationwide, “Carruthers Smith Arrested on Kidnapping Charges,” the headline read.

Carruthers Smith, of the Smith Import Company family, was arrested by federal agents at his home in Lewes, Delaware on kidnapping charges on Saturday. Among his victims were 95 year old Delia McGinty Dougherty of Brooklyn, New York, and Agents William Hardy and Patrick O’Malley of Washington, D.C. who were in Lewes investigating possible charges of art theft lodged against the accused. Mr. Smith began building the Smith Museum of Contemporary Art in Lewes a town of just over 2,000 inhabitants on the shores of Delaware Bay in 1941, yet the museum famous in Lewes for its Streamline Moderne architecture never opened to the public.

Dr. Ronald Yancey, M.D. of Lewes inspected Agents Hardy and O’Malley, and the miraculously young suffragette Delia McGinty Dougherty, and concluded all were in good health despite the unusual circumstances of their captivity. Carruthers himself was taken by federal agents from Washington, D.C. for questioning and is being held in a detention facility in Wilmington pending trial before the United States District Court for the District of Delaware. No other arrests were made in the raid. Mr. Smith, age 76, was famous in his youth as the captain of industry who singlehandedly supplied the Allied forces in World War II with rubber tires that could traverse the deserts of the North African Campaign and the muddy fields of Northern France and Germany. For his service, he was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 1947 by Speaker of the House Joseph W. Martin, Jr. (R-MA).

One curiosity of the case is the vitality of Mrs. Dougherty, age 95, who Dr. Yancey wrote appears to be physically fifty years younger than her age. Dr. Yancey offered no comment when asked further about her condition. Mrs. Dougherty’s husband, Mr. Peter Dougherty, age 91, of Brooklyn, has lived in Lewes with Mr. Smith since 1942. When asked for comment on his wife’s health, Mr. Dougherty said “I am fortunate indeed to have these next few years to spend with my beloved.” No charges have been filed against Mr. Dougherty. Agent Penelope Wilson, one of the three federal agents who were investigating Mr. Smith told Sophie Fleming of the Daily Whale, the Lewes local newspaper, that Mr. Dougherty was unaware his employer had been imprisoning Mrs. Dougherty in the museum. Mr. Dougherty agreed to stand as a witness against Mr. Smith in the tycoon’s impending federal trial.

This is not the first missing persons case connected to Mr. Smith. In 1941 several workers from the Brazilian branch of the Smith Company disappeared on the job Rio de Janeiro. Brazilian authorities have said they are interested in questioning Mr. Smith.

A spokesman for the federal agency responsible for the raid said no objects were found in the museum’s galleries.