The Poetics of Finality – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

This week, some words about endings.

On the morning of Flag Day, I went to the Linda Hall Library with my parents to see the classic 1951 science fiction film The Day the Earth Stood Still. I knew about this film, but this was my first time seeing it. Beside the story, what struck me most about this film was its tone, pacing, and overall character. After I finished my other two events of the day, the Plaza No Kings Rally where I watched the crowd of 11,000 people rally for democracy, and Mass that afternoon, I returned home tired yet eager to find that same tone. I went looking for it in Rod Serling’s classic series The Twilight Zone. Released between 1959 and 1964 in its first incarnation, this series had scared me a bit the previous times I’d sat down to watch an episode or two. It has an air of fear to it that is reminiscent of the reasons why I generally stay away from horror films. And yet on closer inspection, Serling’s stories tell something that is far less frightening than I first imagined because it’s a theme with which I’m all too familiar.

I came to indirectly know more about Mr. Serling when I moved to his hometown, Binghamton, New York, to undertake my doctoral studies in August 2019. His image isn’t all over town, but it’s a visible reminder of Binghamton’s history and place in the fabric of American culture. In fact, much of the stories that I’ve now watched in The Twilight Zone fit the character of that interior part of the Northeast where I lived from August 2019 to December 2022 quite well. In some ways, not too much of the built environment has changed from Serling’s day 60 years ago. Still, I noticed time and again how the optimism of that postwar era had faded. The same town was there, but some of the energy it once knew was long gone. Having lived my life to date in Chicago, Kansas City, and London, all cities with layers of history and memory, I’ve seen how the current generations have chosen to craft their own layer.

London is a city that holds mementos to its ancient and medieval past while largely built in the form of its eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth century growth at the height of the British Empire. Yet today there are enough futuristic buildings and settings in the capital that it was used as a setting standing in for the space-age galactic capital of Coruscant in the latest Star Wars series Andor. I delighted in seeing familiar places from the Barbican Estate and Canary Wharf in the show.

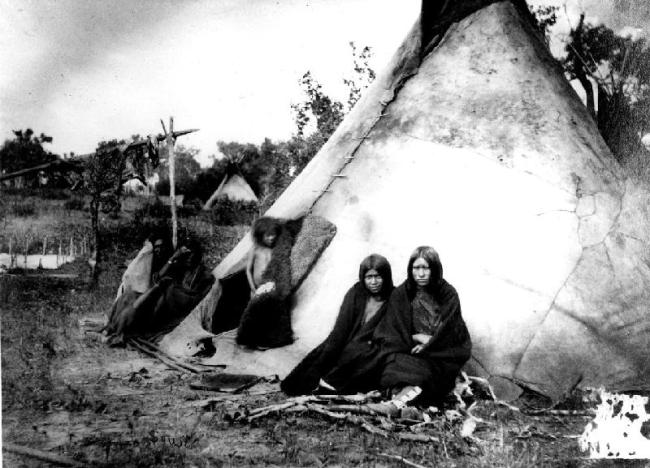

Chicago has some of the same American character of Binghamton and the Northern states as a whole, a common history. Yet Chicago is the powerhouse of this country, the beating heart of our transportation network, the real crossroads of this nation. Where other industrial cities in the Great Lakes faltered in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s Chicago instead continued to power on for its sheer size and the diversity of its industry. Today, it has a very particular character which I believe makes it the most American city this country has to offer for its marriage of American settler culture and all the different indigenous, migrant, and immigrant communities that make America the patchwork of peoples in one great republic that it is.

Kansas City meanwhile saw more of the downturn for its smaller size and some of its traditional industries haven’t translated as well into the current information revolution. Kansas City once thrived as another great railway hub: the Gateway to the Southwest as the last major Midwestern metropolis along the Santa Fe Railroad as it drove across the prairies toward New Mexico, Arizona, and Southern California. Today, our interstate highways direct traffic through Kansas City more from Texas, Colorado, the Dakotas, Iowa, Minnesota, and points east than in the old northeast-to-southwest alignment of the rails. Recently while I was in downtown Kansas City, I remarked on how underwhelmed I felt visiting there for the first time after the business and thrill of going with my parents down to the Loop on weekends when we still lived in Chicago. Kansas City however has seen a renaissance of its own in the last twenty-five years that has filled in many of the gaps left by urban renewal and restored this city’s vitality. That more than anything else made my move to Binghamton a tremendous culture shock: going from a growing city to one that was a shadow of its former self struggling to invest in its future.

For every Twilight Zone episode there seems to be a fearsome unknown menace looming over the story; something that the character can perceive the effects of yet can’t quite see. Yet if there is any common thread to this menace it’s that it is a fear of the unknown. In the original pilot that launched the Twilight Zone, titled “The Time Element,” Serling’s rational psychoanalyst foil to the main character trapped in his dreams concludes through his logic that his dreams that he goes back in time from 1958 to Pearl Harbor on December 6th, 1941 could not be real because any incident that happened in this dreamed 1941, if real, would impact the patient as he lived in 1958. Yet reason is proven unequipped to address the irrational, how can it explain what it intrinsically is not? I’ve argued time and again here in the Wednesday Blog that this is where there exists room for belief in a life lived rationally. Still, having watched a fair number of Mr. Serling’s stories now, I think I can say something to this menace’s true character.

There is an intrinsic fear that comes with knowledge of seeing that we do have an ending. On a biological level, our bodies can only continue working for so long. We drift apart from our lives as they were in one moment or another, apart from friends who we admired and loved in a given moment, apart from jobs that consumed our waking and sleeping thoughts, apart from situations which challenged us to become better versions of ourselves. Yet, all those lived moments will continue on in our memory, at least for a time. I was stunned to find how well I could remember very particular moments of minute detail earlier this year when prompted by a sudden and wonderful realization about how I want to live in my life to come. Even the smallest of details that my senses perceived were there, locked away. The antidote to any fear is joy, and for me it was the most radiant joy I’ve felt in years which unlocked those memories for me of moments which led to that jubilation. Still, fear in moderation is a good counsel, a wise friend. It’s what makes me watch for traffic when I’m crossing the street here in Kansas City, or that advises me to make certain decisions over other ones at a very fundamental level to keep me alive. This is one interpretation of what the infamous tree in Genesisportended: that once humanity ate its fruit we would never again be able to be innocent from seeing flaws in the beauty of nature and in the beauty of ourselves.

Over the weekend then, I went to see the new Stephen King film The Life of Chuck starring Tom Hiddleston as Charles Krantz. I particularly grew to like young Chuck’s grandfather played by Mark Hamill. If I were to compare Stephen King’s writing to any other American storyteller of the last century it would be Rod Serling. Both tell stories of this same menacing fear. Yet in King’s Life of Chuck, the monster who’s revealed in the last scene is far more familiar, ordinary, and known to us all that I saw it less as a menace and more as a companion. There is intense poetry in both Serling’s Twlight Zone and King’s Life of Chuck around endings. They tell us that the finality of moments in our lives and of our lives all together give our lives greater meaning and purpose. I’ve found in the various projects and events I’ve helped organize that we get more done when we have goals we’re trying to achieve and a timeline by when we want to achieve those goals. I often work better when I have deadlines because if I begin to feel impatient at how long something might take, I know there’s an end date to look forward to. I feel that about little things but not the big ones, not the experiences that’ll one day make for good stories or about my life itself.

I for one don’t want to live forever, I worry that’d take some of the meaning out of my life. I would like to be remembered for my writing, for being a good person, for the history I research and leave for generations of graduate students to muddle through in their coursework. On a recent digital security Zoom call that I attended we were asked to search our names on several search engines and see what came up. Should there be anything we didn’t want searchable we could then get that removed. I was delighted to see that after my website, social media profiles, and various conference programs came page after page filled with essays published here on The Wednesday Blog. I suppose that’s one benefit of writing this weekly for the last four years: my thoughts written here will be remembered at least by the search engines. Yet I think the Wednesday Blog will have more meaning when I decide to set it aside and turn my staff to other facets of “my so potent art” to borrow from Prospero. Because then anyone who is curious enough to glance through these pages will be able to see them in their totality and know these essays are artifacts of the time when they were written in the early 2020s at a time of my life of doctoral study that feels so very close to ending.

This is not the last time you’ll hear from me on the Wednesday Blog, rather I’ve decided to end my weekly publication of this blog at the end of the current season. This is Season 5 of the podcast, or Book 6 of the blog itself. I feel that it’s had a wonderful run, and it’s been a great outlet for me while I’m biding my time as my career slowly begins. Yet now, I’ve got a lot more writing to do from new research papers to submit for peer-review to book reviews that it’ll be nice to take this off my docket. This is the 25th issue of this season, and I have a further 15 issues planned before the end. Thank you to all my readers over the last four years and all my listeners over the last three. I hope this will be an ending worthy of your curiosity.

Netflix’s new two-hour film The Two Popes starring Jonathan Pryce as Pope Francis and Sir Anthony Hopkins as Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI is theatre, pure and simple. It falls into one of the most classic sorts of plays, a dialogue between two men with similar positions yet very different experiences. While not all the conversations that make up The Two Popes may have happened, according to an article in

Netflix’s new two-hour film The Two Popes starring Jonathan Pryce as Pope Francis and Sir Anthony Hopkins as Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI is theatre, pure and simple. It falls into one of the most classic sorts of plays, a dialogue between two men with similar positions yet very different experiences. While not all the conversations that make up The Two Popes may have happened, according to an article in

against a slanted cave wall to recover, and another 45 minutes for the rest of the group to return.

against a slanted cave wall to recover, and another 45 minutes for the rest of the group to return.