On Genealogy – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

This week, I discuss how my experience working with genealogy databases helped prepare me to be a professional researcher.

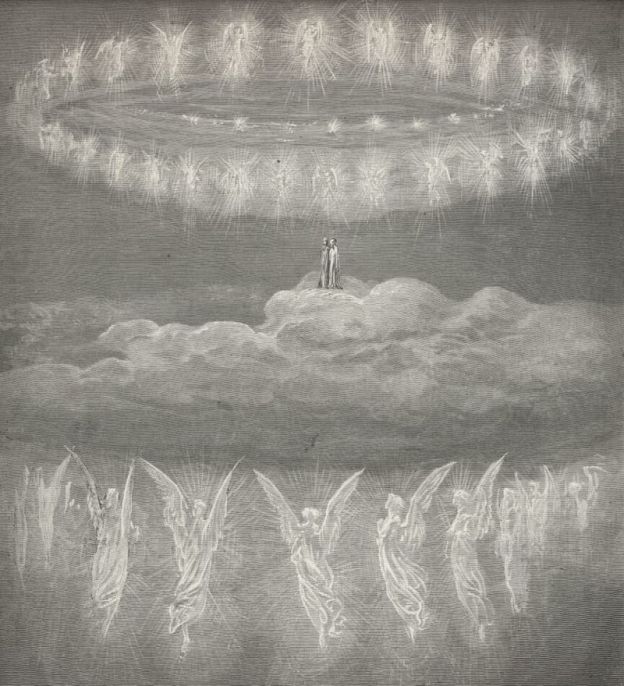

One of the things that struck me about the history that I liked to read as a child was that few of my own ancestors’ names appeared in those books. I remember sitting up late at night in my elementary school years reading these fifty or sixty year old children’s histories of the Vikings and the Romans and imagining the illustrations to life. I could convince myself that I could hear, even on the softest level, the oars of the longships pushing with the current of the Thames as the ropes that tied their sterns to the pillars of the old Roman London Bridge grew taught. I’d return to my regular school day the following morning, to Mass and eight hours of classes introducing me to everything from basic mathematics to orthography and English grammar to music, yet when we had our hour in the school’s library the books I knew to search for were the histories.

My elementary school, St. Patrick’s in Kansas City, Kansas, was founded in 1949 and most of the history books dated from the late ‘40s and early ‘50s, by modern standards they were historical artifacts in themselves. Moving forward I didn’t have access to the same kind of library after my middle school years, my high school had a “media center” that functioned like a library, yet I never remember finding books to read there. So, one of the first places that I went on arriving at Rockhurst University in August 2011 was the upper floor of the Greenlease Library to wander around with my new friends and see what books lived there. I made great use of that library during my four years at Rockhurst, and before the pandemic continued to occasionally check books out with my alumnus privileges.

Yet when I was probably 8 or 9, on one trip back to Chicago my grandmother Mary Lou Kane gave me a book about Irish folklore, and I began to hear stories about my family’s history from her and other relatives. I’d known our ancestors were Irish for as long as I could remember, I was 7 when my grandfather’s aunt Catherine McDonnell died; she was one of the last immigrants and probably the last native Irish speaker in our family. Just before my 10th birthday on a trip to England I met my Welsh cousins who introduced me to that side of my maternal family. We kept in contact writing letters back and forth every now and again.

This all led to my formal introduction to genealogy when I was 13. At that point I talked my way into starting as a volunteer at the institution then known as the Irish Museum and Cultural Center, now the Irish Center of Kansas City. The director at the time thought I was 16 but let me stay after I showed I could be responsible. There were days where I was the only one in the little office we had in the lower level of Union Station, and among my responsibilities was to help the frequent visitors with genealogy questions about their own Irish ancestors. I became familiar with the different genealogical databases around then and steadily built up a good knowledge of where to look for what sorts of records and had the occasional success finding a long-lost relative for someone. I continued volunteering at the Irish Center until around my 19th birthday, when now an undergraduate at Rockhurst with a growing list of clubs on top of my three majors and two minors I stopped volunteering at the Irish Center.

I’ve had a fair bit of luck with researching my own family history. My own database is built upon the work of several relatives on both my paternal and maternal sides who did a lot of the initial research. What I’ve done is to fill in some of the gaps and to elaborate on the circumstances of these people’s lives. This has come into handy here and there, I was fortunate enough to visit the building where my Finnish 4th great grandfather worked as the town judge in the southwestern port town of Rauma in the mid-nineteenth century. Moreover, my Dad wouldn’t have his Irish citizenship through descent were it not for the research done by myself and several others that helped find his grandparents’ birth certificates.

My one genealogy position as an adult that I undertook was as a volunteer in the genealogy reading room of the National Archives’ Kansas City regional office. I regularly attended to this position for a good year and a half while I was beginning my M.A. in History at UMKC. It was fun at times, though in many other occasions it could become quite dolorous as the cases I was often presented with were unsolvable or restricted in some ways or another. I left that position as my work at UMKC began to grow, around the time I started writing my second M.A. thesis in fact.

All this research that I’ve undertaken for myself and others in genealogy helped prepare me for my work as a professional historian where so much of what I do is search through databases looking for archival sources that will offer the glimpses into the past that I need to write my work. At some point once I feel confident that I’ve done enough historical research to earn my first professorship I intend to turn to the boxes of family papers collected by long-time Wednesday Blog reader Sr. Mary Jo Keane, one of my grandfather’s cousins, whose research is the foundation of what I know about my paternal family in Mayo. When she died, I took those boxes with me with the intention of writing some sort of family history like the one she intended to write in her last years.

We often talk in the historical profession about history from below as one of the newer genres of history-writing. I’ve liked this idea since I first heard about it, and in some sense, I’ve tried writing from the perspective of the animals which are at the heart of my professional research to varying success. Genealogy is often history from below because as much as we may hope to find some famous ancestor––at one point Ancestry.com claimed to prove my relations to several famous people––it really ought to be a recognition of who our family has been in the generations that we can still find. It is a supplement to memory even as that living memory of our past fades. At Kane family funerals I would often learn something new about the immigrant generation in my family, my great-grandparents, that would explain their lives just a bit more. Those stories turn these people from just being figures on paper into memories that have some of the color and life of those illustrations in my childhood history books. I want to know more about my family’s past to understand how I fit into our world today with its progress and troubles all the same. In the first half of the last century that generation lived through world wars, the Irish War for Independence and Civil War, the Great Depression, and a global pandemic. And through it all they took the bold step of leaving home and starting a new life for our family in Chicago. That life was the one I was born into at the end of the last century, and even after my parents & I moved to Kansas City that life in Chicago still forms the bedrock of my life and perception of things today. None of this would be nearly as personal or as impactful if I knew nothing about the ancestors I never met. It’s thanks now to all this research in genealogy that they live on in my memory today.