I was 27 when I arrived here in Binghamton at the start of August 2019. I made a big move out here, with immense help from my parents, and set up shop in a good-sized one bedroom apartment that’s remained my sanctuary in this part of the country ever since. I’d wanted to continue my education up to the PhD since my high school days, and it’s a plan I’ve stuck with through thick and thin. After a false start in my first attempt to apply to PhD programs in 2016, which led to two wonderful years working on a second master’s in History at the University of Missouri-Kansas City (UMKC), I applied again, now far better positioned for a PhD program and ended up here through the good graces and friendly insight of several people to whom I’m quite grateful.

Arriving in Binghamton though I found the place very cold and quite lonely. In recent months I’ve begun to think more and more about getting rid of some of my social media accounts only to then remember that Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter were some of my greatest lines of communication with friends and family back home in Kansas City and elsewhere around the globe throughout these last three years. That first semester was tough, very tough, and while the second semester seemed to get off to a good start it was marked by the sudden arrival of the Coronavirus Pandemic and the end of my expectations for these years in Binghamton.

I spent about half of 2020 and 2021 at home in Kansas City, surrounded by family and finding more and more things to love about my adopted hometown with each passing day. When I was in Binghamton it was to work, in Fall 2020 to complete my coursework and in Spring 2021 to prepare for my Comprehensive Exam and Dissertation Prospectus defense. I still did a good deal of the prospectus work at home rather than here, though the memories of those snowy early months of 2021 reading for the comps here at this desk where I am now always come to mind when I’m in this room.

As the Pandemic began to lessen in Fall 2021 and into the start of this year, I found myself in Binghamton at a more regular pace. There was something nice about that, sure I wanted to be home with my family, but I also felt like I was getting a part of the college experience of going away for a few years to study that was reminiscent of the year I spent working on my first MA at the University of Westminster in London. I started to venture further afield in the Northeast again, traveling to Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington again. When I first decided to come here one of the things, I decided was I’d take the opportunity of being in the Northeast to see as much of this region as possible.

2022 saw another transition, I wasn’t in one of the newer cohorts in my department anymore. Now, in Fall 2022 I’m one of the senior graduate students. It’s a weird thing to consider, seeing as it felt like 2020 and 2021 evaded the usual social life of the history graduate students here, thanks to the ongoing pandemic. I also began to look more seriously at my future, applying for jobs in cities across this country, and even looking again at some professorships, something I doubted for a while would be an option for me. If there’s anything about life that I’ve learned over the past three years spent here, it’s that you always need to have things beyond your work to look forward to. Whether that be a long walk in the woods on the weekends or a day trip to somewhere nearby, or even the latest episode of your favorite show in the evenings. Doing this job without having a life beyond it is draining.

For me the best times here in Binghamton were in Fall 2021 and Spring 2022 when I truly began to feel like I had a place here that I’d made my own. I was confident in my work, happy with how my TA duties were going, and really enjoying my free time as I began to spend my Friday evenings up at the Kopernik Observatory and Sundays at the Newman House, the Catholic chapel just off campus. I was constantly reading for fun as well, something I’d lost in 2020, even falling behind with the monthly issues of my favorite magazines National Geographic and Smithsonian. There were many weeknights I’d spend out having dinner alone reading natural history, science fiction, anthropology, and astronomy books.

It’s interesting looking back on myself from six years ago when I was in London, the months that summer when I decided I wanted to get back into history after a year studying political science. My motivations were to earn a job working at one of the great museums I’d spent countless hours in during that year in the British capital. While I studied for my MA in International Relations and Democratic Politics, I was still spending my free time looking at Greek and Roman statuary and wandering the halls of Hampton Court or watching the hours of history documentaries on BBC 4 in the evenings. And now that I’m back in History as much as I do appreciate and love what I do, I find my free time taken up by science documentaries and books.

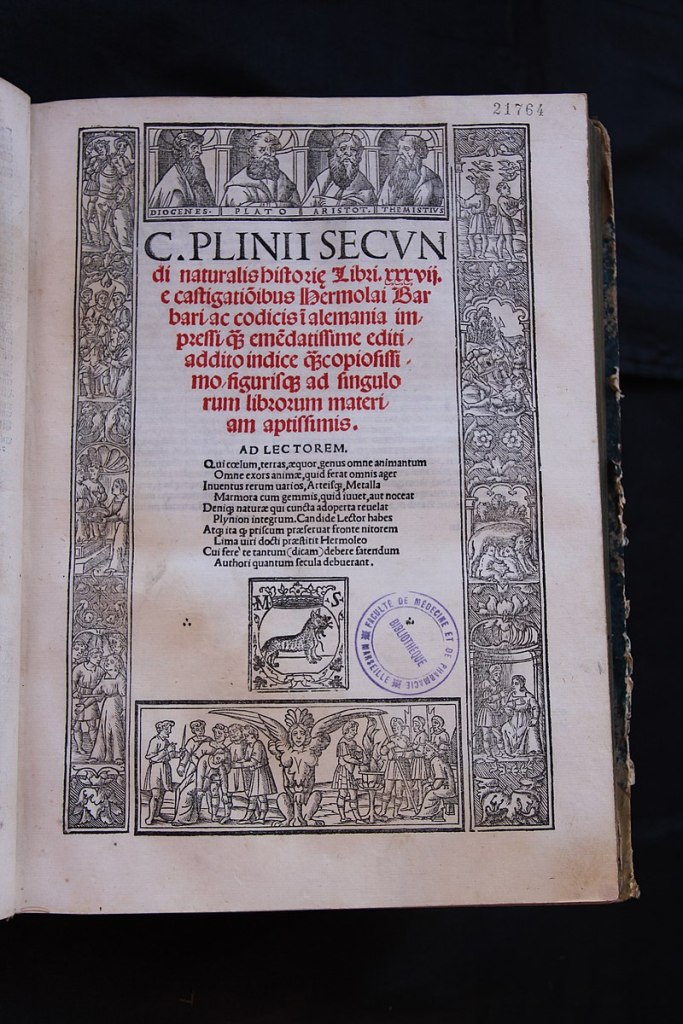

It’s important if you do want to get your PhD in the humanities and social sciences to figure out why it is you want to do this before you start. Have a plan in mind, have a big research question in mind, and focus your attentions onto that question. My own story has many twists and turns from an interest in my early 20s in democratic politics to a brief dalliance with late republican Roman history before settling into the world of English Catholics during the Reformation. I ended up where I am today because of another series of events that led me to moving from the English Reformation to the French Reformation, and from studying education to natural history. So, here I am, a historian of the development of the natural history of Brazil between 1550 and 1590, specifically focusing on three-toed sloths. In a way there are echoes of all the work I’ve done to date in what I’m doing now, thus as particular as this topic is it makes sense in the course of my life as a scholar.

A month from now will be my 30th birthday, a weird thing to write let alone say aloud. My twenties have been a time of exploration of both the world around me and of myself. When I look at my photo on my Binghamton ID card, the best way to describe my appearance would be grumpy yet optimistic. Just as I was a decade ago, a sophomore in college, so now I am today, looking ahead to the next decade with excited anticipation of what it’ll bring, and hopeful that all the work I’ve done in this decade will find its reward in the next.