On Drink – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

This week, bringing together my research and my life through wine.

As I progress in my efforts to prepare my translation of André Thevet’s (1516-1590) Singularitez de la France Antarctique for publication, I find myself often laughing at Thevet’s own comments about his world and the worlds he visited on his 1555 voyage from France to Brazil and his 1556 voyage home (the one with the whales). Thevet was a Frenchman through and through, yet while he referred to “our countrymen” on several occasions in the Singularitez he more often identifies himself alongside other Europeans as Christians, distinguishing them from the African and Amerindian peoples he described in various forms of other. Thevet used the broadest possible perspective to craft a story which would resonate with his reader, a story which told of the influence and impact of his fellow Christians from “our Europe” upon these distant worlds across the “Ocean Sea.” I like Thevet’s perspective because as contemporary to the middle of the sixteenth century it is, it still feels contemporary to our own time all the same. If the frontiers of mapped knowledge were just beyond the Atlantic and Pacific shores of the Americas in Thevet’s time, today they lie in the vastness of Space above us. The parallels between the First Age of Exploration to which Thevet contributed and our own Second Age of Exploration now underway are many and ought to be explored further in academic scholarship.

I’ve long loved reading about explorers, pioneers, and settlers. Over the weekend then, when I drove west with my Dad to Hutchinson, Kansas for the 2025 State Convention of the Kansas Ancient Order of Hibernians I made a point of us going to visit the Cosmosphere, one of Hutchinson’s jewels. This museum of spacecraft, memorabilia, and historical artifacts from the 1940s through the end of the Cold War is something worth visiting if you’re in Central Kansas. We’d been there before in about 2007 or 2008 with my Boy Scout Troop to do our Astronomy merit badge. The rest of the weekend was spent enjoying the company of our brother Hibernians and their wives, and in a long business meeting on Saturday in the Strataca Salt Mine Museum just outside of town. While I was in Hutchinson, I made a point of continuing my work on typing out the French original of the 1558 Antwerp edition of Thevet’s book for my impending book proposal. The chapter I worked on in Hutchinson, “On Palm Wine” was one such boozy treatise that made me laugh.

Thevet diverted on several occasions from his cosmographic endeavors of describing the botany, ethnography, geography, and zoology of these places to rest instead on their local wine, or wine substitute. He began these series of diversions on Madeira, still today famous for its wine, “which is first among all other fruits of usage.” Thevet made his case concerning wine plain from the start, writing of the Madeiran variety that it is “necessity for human life.” Vines grow on Madeira, Thevet wrote, because “wine and sugar have an affinity for Madeira’s temperature.”[1] Its wine is comparable to Cretan wine and “the most celebrated wines of Chios and Lesbos,” which Thevet identified as Mitylene. Here, he equated a modern creation, the plantation of Portuguese vines into the soils of Madeira, to the famed wines of antiquity which were prized by the Greeks, Romans, and Persians alike.[2] Thevet couched his qualifications of the greatness of modern things on their parallels with or roots in antiquity. A humanist, Thevet’s cosmography was reliant on these classical framings to assess the proper place and due of these things of which were “secrets most admirable, of which the ancients were not advised.”[3] Maderian wine was better aged, Thevet wrote, “for they let it rest under the ardor of the Sun kept with the times so that it doesn’t keep the natural heat in the wine.”[4] In a place such as this warm enough where sugar cane could be planted in January, Thevet found a paradise where even he and his countrymen could appreciate the local grape.

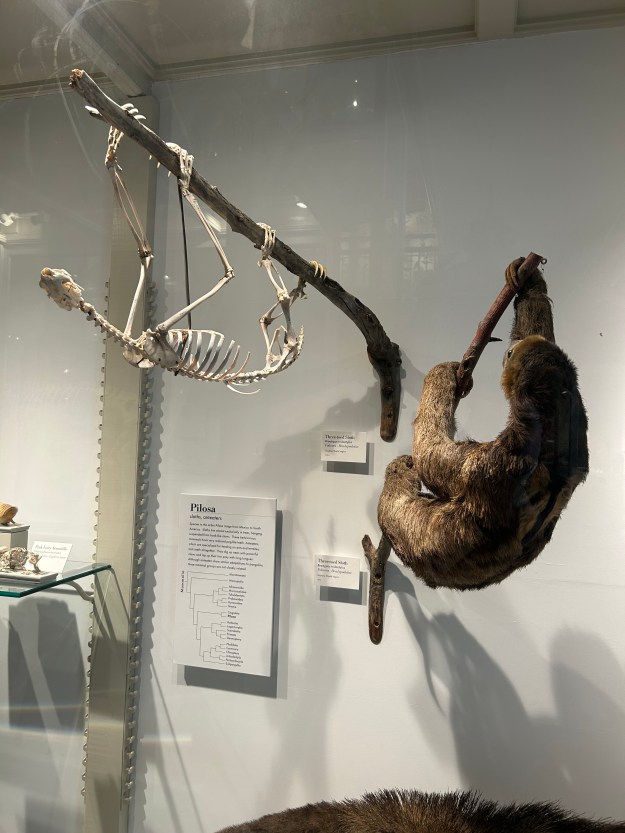

Two chapters later, as Thevet moved on to describe the coastline around the Cap-Vert in Senegal, the westernmost promontory of Africa and the place whence the island Republic of Cabo Verde derives its name, he stopped again to discuss their local drink, in this case palm wine. Thevet recorded an indigenous name for this drink, Mignol in his Singularitez, which Émile Littré’s Dictionnaire de la langue française recorded is a “spirited liquor extracted from a species of palm.”[5] Perhaps then, Thevet’s use of the term may be the first introduction of this word into French. He writes, with a hint of a sigh that “the vine is unfamiliar to this country where it has not been planted and diligently cultivated,” resulting in a dearth of wine and the preference for liquors extracted from palm trees. This makes wine one of the most human of inventions, something that needs labor to be crafted out of natural things. It is a bridge between the twin categories of collected objects in the cabinets of curiosities of Thevet’s time: artificalia, that which was made by human hands, and naturalia, that which was made by God.[6] While the palm “is itself a marvelously beautiful tree and well accomplished, larger than many others and perpetually verdant” Thevet contended that its fruit still requires less cultivation and work than the fruit of the vine or barley.[7] “This wine is excellent but offensive to the head,” he wrote, noting that it “needs a hot country and grows in glassy sand like salt, lest its roots end up salting when it is planted.”[8] Unlike grape wines, palm wine is “prone to corruption” because, Thevet wrote, “humidity rises in this liqueur.”[9] It is similar in color “as the white wines of Champagne and Anjou and tastes better than the ciders of Brittany, helping the locals who are subjected to continuous and excessive heat.”[10] I infer in here a slight toward the Bretons, who were only recently made subjects of the French crown in 1547 upon the coronation of Henry II of France as both King of France and Duke of Brittany.

Thevet’s point is that while alcohol can come in other forms than just the fruit of the vine, that is far superior to any other drink. I myself prefer wine, especially reds from Chinon, Rioja, and the Burgenland. I’ve had my fair few opportunities to enjoy a glass or two, or perhaps more. Polyphemus put it well when he cried out that Odysseus’s full-bodied wine must be “nectar, ambrosia [which] flows from heaven!”[11] The holy vines whence come wine carry into Christianity and in particular the Catholic and Orthodox traditions. Through transubstantiation the wine becomes the Blood of Christ. To me, this is the greatest mystery of the Faith, or at least the greatest mystery of our liturgy and rite. I find it amusing that other churches have non-alcoholic grape juice rather than wine fill this role, as in our Catholic culture there’s a certain degree of pride in the fact that we use wine proper, and that everyone partakes (if they so choose) in that wine as early as 8 years old at their First Communion. I for one think that a gradual introduction to alcohol within the right guarded circumstances can be healthy; this at least avoids the taboo that can lead to underage drinking as an act of rebellion. Yet by making drink a central tenant of our ritual life, we give it a clear place where it should remain and distinguish it from those places where it should be avoided. For instance, I customarily only drink whiskey in toasts at weddings and funerals or other special events. It’s not something that I want to have on a regular basis.

This regularity is central to our society’s relationship with alcohol. I grew up with the image of drink being embodied in the alcoholic model of Fr. Jack Hackett, played with a finesse by the late great Frank Kelly on the Channel 4 sitcom Father Ted in the 1990s. Fr. Jack’s favorite word was “drink!” always said in an exclamatory manner. Drink has its charms to be sure, yet like anything it should be taken in measure. Too much and you lose control of yourself or even your sense of self all together. Too little and you cannot really enjoy it. A century ago, American society responded to alcoholism by trying to stifle its main fuel through prohibition. The 18th Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibited the sale of alcohol, yet it was hardly effective in this effort. One of the funnier papers I wrote in my undergraduate made the satirical case that Catholicism has advantages over Protestantism because we didn’t think that Prohibition would actually work. Granted, we are the Church that had the Index of Prohibited Books, so we all make mistakes. I think a similar mistake can be made in the idea of wholesale prohibition of actions and things that are controversial today. I for one am more in favor of restricting gun sales, yet a ban simply would not work in the United States. Likewise, my Church is a loud and vocal advocate for the prohibition of abortion. In both cases, these feel like measures at undertaking a complicated surgery with a battleaxe. Instead, let’s consider the underlying societal causes of these issues and address those. Let’s bring together this country’s finest minds, experts in their fields, and have them work together to find a solution that will improve our lives and leave this a better place for our descendants to live.I do enjoy a good glass of wine. I’ve had both good wine and the bad wine to compare it to. I’ve drunk wines so bad that they make your typical communion wine taste like a nice, aged vintage. A good glass of wine elevates a meal for me. On New Year’s Eve during my prix fixe dinner at Paros, a Greek restaurant in Leawood, Kansas, I enjoyed a well-rounded Cretan red with at least one of my five courses. At the end of the meal after the lamb shanks and the octopus and the baklava and everything else I was so content that I didn’t feel the need to continue the festivities. Rather, I let the rest of the night pass by in peace and quiet. A good drink can add in the sweetness of the day, an evening’s amber glow that could just as easily be missed. It remarks on the passing opportunities that if only we saw them we might make different decisions that would make our lives even just a little bit better.

[1] Thevet, Singularitez, 14v.

[2] Thevet, Singularitez, 15r.

[3] Thevet, Singularitez, 159r.

[4] Thevet, Singularitez, 15v.

[5] Émile Littré, Dictionnaire de la langue française, 4 vols., (Paris, 1873-1877) s.v. « mignol. »

[6] Florike Egmond, Eye for Detail: Images of Plants and Animals in Art and Science, 1500-1630, (Reaktion Books, 2017), 30; Mackenzie Cooley, The Perfection of Nature: Animals, Breeding, and Race in the Renaissance, (University of Chicago Press, 2022), 101.

[7] Thevet, Singularitez, 18v.

[8] Thevet, Singularitez, 19r.

[9] Thevet, Singularitez, 19v.

[10] Thevet, Singularitez, 19v-20r.

[11] Homer, Odyssey 9.403, trans. Fagles.