Mirrors – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

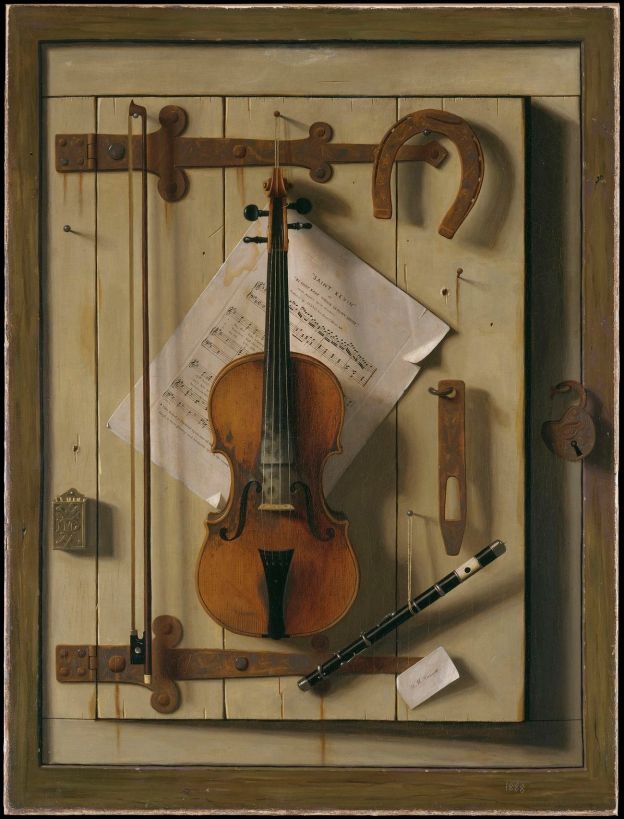

For a few years starting when I was thirteen, I took lessons in traditional Irish music from a good friend named Turlach Boylan who is quite talented on the flute, tin whistle, and mandolin and plays locally in sessions. I had potential but never really got there, in part because I didn’t practice as much as I should’ve, yet also in part because I kept running up against a sort of translucent wall of my own self-consciousness. After a while when we were both around during sessions, Turlach would invite me to come join the circle and play with the other musicians. I’d try but often when I’d hear someone else playing with me, I would burst into a big smile and have a very hard time playing my tin whistle with the group.

There’s something about playing an instrument with a group of people in such a loose and lively manner as in a trad session that has been hard for me. This week I read a story in Commonwealabout the joyous experience of all the craic that goes on in the trad sessions that the author, Commonweal‘s managing editor Isabella Simon, had joined in New York City. It made me think more that perhaps in that context my fear was less a shock at the fact that I was playing with other people but the worry that I’d mess things up, play the wrong note, or not know the jigs, reels, polkas, waltzes, and airs they were playing. As Ms. Simon wrote the talent of a session player is judged not in their virtuosity but “by whether the listeners are tapping their feet.” That clicked for me because that is how I approach teaching and lecturing, the expertise and skill that I exhibit in the classroom is a big part of the puzzle, yet it is one half of the whole picture which is best filled out by a comfort and ease with entertaining my audience and keeping them engaged.

I’ve found that difficult the last few days as I’m starting my new teaching job, sometimes I’m not sure my messages are getting across, especially when I have to shout over a room of excited students. Still, it’s not an unfamiliar lesson for me. One story I’m sure I’ve told on this blog before is about an icebreaker presentation that I gave in my Junior Year AP English class in high school, where our teacher asked all of us to bring in baby pictures of ourselves that she could hang up on the back wall of her classroom. When I got up to present my own picture, I let slip that I had considered bringing in a picture of a monkey to say that “I was a very hairy baby,” a line I think I partially stole (lovingly indeed) from Father Ted‘s milkman episode. Still, the picture I showed to the class was of a very large ancient tree on the grounds of Canterbury Cathedral with my Dad and I barely seen near the base sitting on a park bench. My classmates laughed at the whole routine, and I returned to my seat at the end of it feeling really good about myself; my fear that they’d all be laughing at me was avoided by telling the joke rather than being the joke.

In my teaching, I like to keep things loose, to have more of an improvisational style that changes to fit the room. That worked well at the university level and is kind of working here with the middle schoolers, but with more guidance from myself to make sure they’re doing what they need to be and getting the correct information about the day’s subject in the moment. I tend to not have the same kind of stage-fright that I used to, I can usually get up in front of a crowd and say what I need to, yet I do judge the room every time. There have been moments when I’ve started talking and I can immediately tell most of the people in the room either don’t care or actually are sitting there against their will. In those cases, I keep things brief. If I can play around with an audience though I’ll have more fun and will weave different stories together.

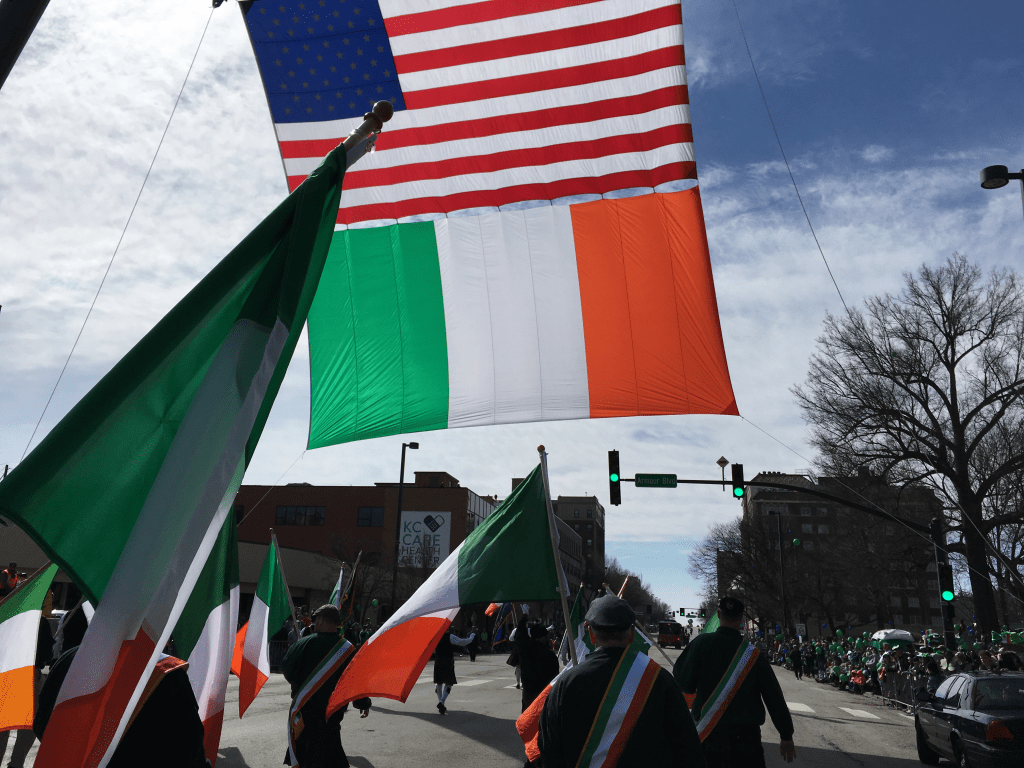

I love music, from the structured virtuosity of a fine orchestra like our own Kansas City Symphony to the fluid vitality of an Irish traditional session and all the great jazz in between. I love how it can express things that mere words could not annunciate. Yet where Irish music shines is in its ability to keep that conversation, no matter how joyous or sad, beyond one tune and into the next. In that moment the memories of generations of musicians can be heard, their voices echoed in the instruments and songs of their students which keep this rich tradition alive and well.

The lesson I’ve learned in all of this, which Ms. Simon’s story clarified for me, is that all life is a performance, and in the moments when I can relax and see past the mirror in my mind, I’ll be okay. In all the things I’ve tried for personal enrichment, from learning French and Irish to learning how to skate on ice after the Pyeongyang Olympics in 2018 to standing on stage in front of a full house, I’ll be okay as long as I don’t think about the fact that I’m putting myself out there too much, taking that risk of ridicule. My stage-fright will only ever be experienced by me and me alone. And at the end of the day if I’m comfortable with my own performance, if I play to the internal audience as well as the external, then I’ll be happy. To paraphrase something the gentlemen of the Monty Python troupe once said, “we only write jokes that we think are funny.” In those sessions, I’m playing not just for my own ear, but to be a part of a circle of friends united by our common musical language, at ease with each other’s company, rejoicing evermore in that fine moment.