On Simplicity – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

This week, how the greatest wisdom is simple in nature.

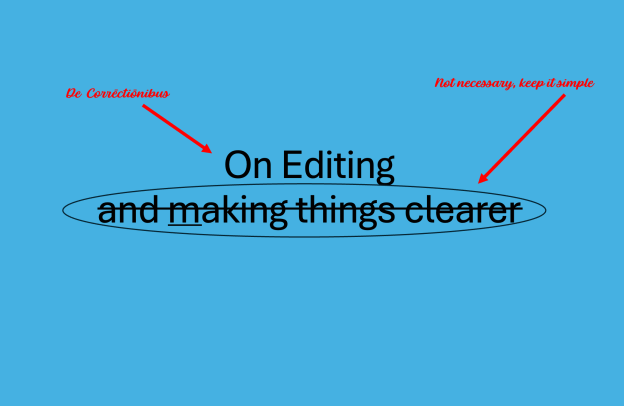

Over the last several weeks I’ve written about forms of knowledge and knowledge collecting. Knowledge is easier to identify, as it is empirical in its core. Yet on a scale even beyond knowledge lies wisdom, the cumulative sum of humanity’s understanding of the underlying character of human nature. It’s very easy for me to get bogged down in words, words, words and tie myself in knots which I find nigh unbreakable and even more undecipherable. Yet amid all those layers of paint there are often gems which merely need good editing to illuminate. This is what fills my days today, a big edit which I hope will signal the beginning of the end of my years of doctoral study.

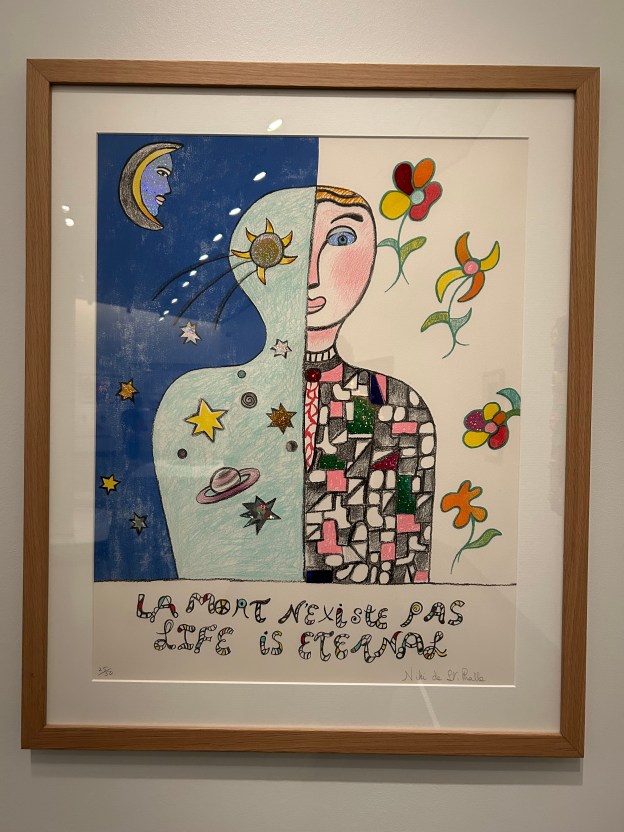

In these years, while I’ve devoted my days to reading histories of the Renaissance intersections between the Americas and France, I’ve made a point of reading for fun all the same. I need to read things not related to my research for the escape they provide. At times these fun readings have been more thoroughly connected to my research, as in my recent choice of Jason Roberts’s Every Living Thing, yet in Binghamton I spent many happy evening hours reading Star Trek anthologies and novels while returning to my vocation each day. Of the stories that I’m drawn to, I enjoy reading books and watching films with characters that embody a certain lived experience that begats wisdom. Recently, this desire for such a character led me to read Peter Bien’s new translation of Nikos Kazantzakis’s Zorba the Greek: The Saint’s Life of Alexis Zorba. This is phronesis. Zorba’s wisdom is one that’s been gathered over the sixty years of his life and funneled toward living a good life as he sees fit. His is a simple wisdom which recognizes the physical limitations of the body in opposition to the limitless potential of the soul. I loved the first dance scene in Zorba the Greek in which the old miner erupted upward from his dinner and began to leap about. Kazantzakis describes it as though his soul could not be contained by his body and that it was that spiritual essence which spoke so fervently and wordlessly of its own joy. Kazantzakis can make even the simplest of scenes appear elegant and luminous. His description of the passage of time on the Mediterranean reaching up from Africa to the southern shore of Crete is one of my favorites. Here, I quote from Bien’s translation with the affection that beautiful prose deserves:

“The immense sea reached African shores. Every so often a warm southwest wind blew from distant red-hot deserts. In the morning the sea smelled like watermelons; at midday it vented haze, surged upward discharging miniature unripe breasts; in the evening, rose pink, wine red, eggplant mauve, dark blue, it kept continuously sighing.”[1]

The wisdom inherent in Kazantzakis’s prose lies in his ability to evoke the variable texture of nature, the changing face of it with the passage of the day. I remember once in Binghamton I have the idea to take a selfie once an hour throughout the day to see how my face, hair, stubble, and what not changed as the hours passed. I know for instance that if I want to have a lower register in my recordings of this Wednesday Blog that I need to record first thing in the morning when my tenor is closer to a baritone. This week, owing to a general sense of exhaustion, I haven’t gotten around to writing this essay until nearly 90 minutes before when the podcast normally publishes. Rather than force myself to write something earlier in the day I waited and gave myself the time to think of something good.

Wisdom is knowing that worrying won’t get you anywhere; it lies in the peace of mind and heart that keeps us happy and healthy. This evening, while I was having dinner with one of my best friends and his wife and young son, I brought up my particular conundrum of the day. Jokingly, the suggestion that I write about simplicity was made. I shrugged, thinking of William of Ockham, one of Bill Nye’s favorite history of science examples to use, and decided to run with it. After all, often the wisest people that I’ve met are the ones who embrace the simplicity of living a life embracing their own nature. The wise know that they are going to grow old and die and don’t worry about it. I find myself thinking of this as I watch without much resource as my hair recedes. I’ve joked that my particularly follicly impaired genes may require an eventual investment in a variety of hairpieces for different degrees of formality. I’ve grown in my own comfort with taking care of myself, applying sunscreen before going out on walks around the neighborhood now to mitigate the inevitable that comes from having largely Irish genes and living in the far sunnier Midwestern climate than my ancestors’ rain soaked home soil in Mayo. In his Saint’s Life, Alexis Zorba often doesn’t worry about these things and expresses frustration and even anger when the narrator, his boss, frets about the things he cannot control. I’m better at this than I have been, which is reassuring in some ways of looking at things, yet I still have room to grow.

Wisdom is trusting the people around you to do what they feel is best. If the simplest solution is often the best, then why aim to make things overly complex? Complexity requires forethought, or sometimes is the result of a lack of forethought. Last summer I delighted in writing several essays for the Wednesday Blog attempting to adapt chaos theory to explain human behavior.[2] We need both complexity and simplicity to understand ourselves and the world in which we live. Think about it: we cannot narrow things down to binary options. More often, the binary is one of a series of binaries which together form a logical thought or series. I marvel at the fact that computers most fundamentally work in the binary language of 1s and 0s, and that in this manner language and thought are boiled down to so rudimentary an interpretation. It’s for this reason that while I’m concerned by the rise and development of artificial intelligence and its misuse, I feel a sense of assurance that it is still limited by its basic functions and limited by the abilities of its artifice.[3] The human brain is a wonderous and ever complicated organ which evolved to fulfill its own very particular needs. On the simplest level the brain thinks, it sends directions to the rest of the body to keep the body operating. In a theological framework, I’ve argued that the brain may be the seat of the soul, the consciousness that is at the core of our thought. My earliest memory that I’ve written about here was the first time I recognized that particular voice of my own consciousness, which occurred sometime when I was 3 years old.[4]

Wisdom is intangible, it’s something that you have to learn to recognize. This is perhaps the most complex tenant that represents something simple. In order to truly become wise, one must understand that wisdom isn’t something you can buy off the shelf or write your way into. For all the words which Zorba’s boss writes, allowing them to consume him, he remains feeling unfulfilled in life. It’s why the narrator of the novel struck out from his books and sought to live among ordinary people, buying a stake in a lignite mine on the southern shore of Crete. On his way there in the Piraeus he met Zorba, the man who within a few pages became his foreman and the one who’d realize his idea of finding wisdom in the living world. The simplest explanations are often best. Zorba lives to enjoy the life he has, and when things go wrong––as they often do––he finds something to build upon and start over again.

A couple of months from now I’m going to be contributing my own experiences to a tacit knowledge panel at the History of Science Society’s conference in New Orleans about how I’ve been able to maintain a full research load and writing all year round with hardly any funding at all. I recognize that the circumstances of these past few years have been marked by my own poor decisions and mistakes that I’ve made along the way. Yet in spite of those, and bad luck in many respects, I’ve been able to continue with my work and to produce historical studies that are beginning to make a decent contribution to the history of science in the Renaissance and specifically to the history of animals in that same period. I’m looking forward to that panel, and to the two papers I’m presenting during the same weekend. Maybe, like Zorba, when things feel like they are about to go well I’ll feel the need to rise to my feet and leap into the air as though my soul were attempting to escape from my body. Simply put, for all the trouble that life has brought, joy is overpowering when pure.

[1] Nikos Kazantzakis, Zorba the Greek: The Saint’s Life of Alexis Zorba, trans. Peter Bien, (Simon and Schuster, 1946, 2014), 81.

[2] “Elephant Tails,” Wednesday Blog 5.24.

[3] “Asking the Computer,” Wednesday Blog 5.26.

[4] “On Political Violence,” Wednesday Blog 5.17.