The Essence of Being – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

This week, to begin Season 4 of the Wednesday Blog podcast, I want to talk about what it means to exist. I know, small topic for a Wednesday.

Two weeks ago, I started teaching a new class that I’m calling Bunrang Ghaeilge, Beginner Irish. The students come from my fellow members of the Fr. Bernard Donnelly Division of the Ancient Order of Hibernians and their relatives, and in the first two weeks we’ve progressed slower than I initially expected yet we’re still progressing through the materials. The first verb which I taught my current students in English translates as to be, yet in Irish as two forms: is for a more permanent being and tá in a more impermanent circumstance. In the moment I explained this difference by noting how I say is as Chicago mé (I am from Chicago), as in I was born in the Chicago area, but I say tá mé i mo chónaí in Kansas City (I live in Kansas City). We don’t have this distinction in English, either between the permanent and impermanent versions of the to be verb or in the clear distinction between where you’re from at birth and where you currently live; that distinction is far more subtle in English.

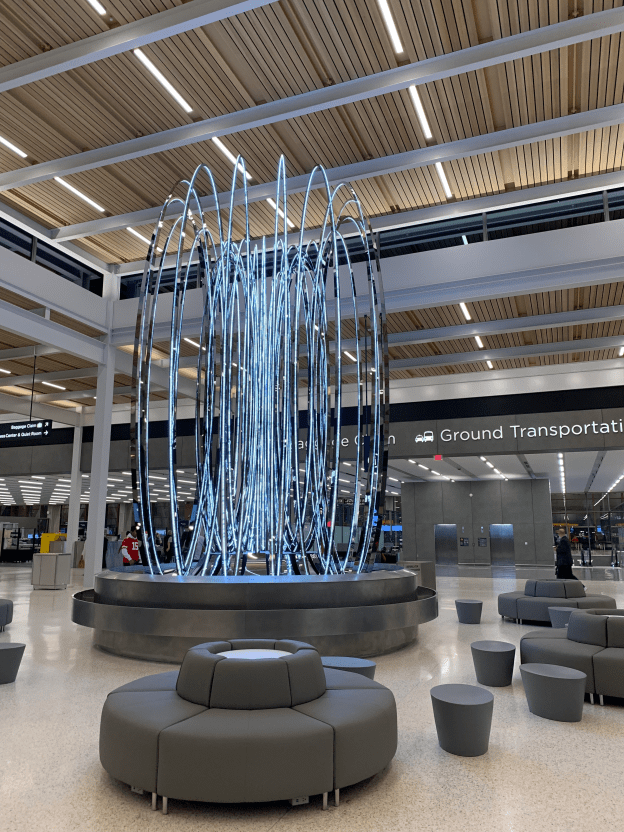

At the same time, I am learning Italian for a trip this summer, my own version of the Grand Tour, and on the Busuu app where I’m learning Italian they taught that I should say sono di Chicago però abito a Kansas City,as in I was born in Chicago, but I inhabit today in Kansas City. This distinction between a place that is central to our essence, the place where we were born, and the place where we now live seem important, yet it flies in the face of the American sense of reinvention that we can make ourselves into whomever we want to be. It’s struck me when I’ve met people who would rather see themselves as from the place where they currently live than the place where they were born. That is a different view from my own, born out of different lived experiences and different aspirations.

This word essence developed from the Latin word essentia, which the 1st century CE Stoic philosopher Seneca wrote was coined by the great orator Cicero as a translation of the Greek word οὐσία (ousia), a noun form of the Ancient Greek verb εἰμί (eimi), meaning “to be.” (Sen., Ep. 58.6) It refers to an innate idea that the ultimate goal of philosophy and learning in general is to better understand the self; the most famous inscription in the ancient Temple of Apollo at Delphi read γνῶθι σαυτόν (gnōthi sauton), or “know thyself.” I add to that goal the aspiration that one can improve oneself.

This time of year, I find myself thinking more and more about what it means for me to be an Irish American. This past weekend we celebrated St. Patrick’s Day, a day of great celebration for the global Irish diaspora and our cousins back in Ireland as well. I’ve written before here about how my communities’ immigrant connections to Ireland often predate the current century, if not the twentieth century as well and how we are in many respects far more American than Irish. In recent years, I began to refer to myself in this subject as an American cousin, after all as much as I have Irish roots and I come from an Irish family, I’m an American and have lived an American life to date. I’m not as far removed from Ireland as many I know, yet this year marks the 110th anniversary of my great-grandfather Thomas Kane’s arrival in America.

There’s something about being Irish American which doesn’t quite fit neatly into any of the official boxes. In Ireland, to be Irish is to be from Ireland or to be a close enough descendant that you qualify for Irish citizenship, like my father does. In America, there’s a sense that the old stereotypes of Irish immigrants are fair caricatures to still uphold, especially on our communities’ holiday in much the same way that the sombreros are donned on Cinco de Mayo. Yet there’s a lot more to it. On both sides of the Atlantic, our communities have the same deeply intertwined connections between families near and far, friends in common, and a sense of nostalgia that I see especially strong among those of us born in America.

Perhaps the Irish language can offer the best answer here. In Irish, I’ll say to Irish people, as I wrote a few paragraphs ago, “Is col ceathrair Meiriceánach mé.” Yet the official Irish name for us Irish Americans is “na Gael-Meiriceánigh”, or Gaelic Americans. I think this speaks to something far older and deeper than any geographic or political connections. We come from common ancestors, share common histories and stories that wind their way back generations and centuries even. We are who we are because of whom we’ve come from. I hope to pass this rich legacy in all its joys and struggles onto the next generation in my family; perhaps I dream of those not yet born hoping they’ll be better versions of my own generation. I hope they’ll still feel this connection to our diaspora like I do even as we continue on our way along the long winding road of time further and further from Ireland.

I am the child of my parents, the grandchild of my grandparents, and great-grandchild of my great-grandparents. In so many ways, I am who I am today because of those who’ve come before me. The geography of my life was written by them, by a choice among other immigrants from County Mayo my ancestors found their way to Chicago instead of Boston, New York, or Philadelphia. My politics reflect my ancestors’ views as well, in the Irish context the legacies of the Home Rule Crisis of 1912-1916, the Easter Rising of 1916, the War of Independence of 1919-1921, and the Civil War of 1922-1924 all have as much of a presence in my political philosophy as does their American contemporaries: the Progressive Era and its successor in the New Deal coalition. Yet I am my own person, and from these foundations I’ve built my own house in as much of an image of the past as it is a hope for the future.

What does it mean then to be ourselves? We hear a great deal today about how people identify, in a way which seems to be a radical departure from older norms and expectations both in the English language and in how we live. We constantly seek answers to all of our questions because we anticipate that all of our questions can be answered, yet the mystery of being is one of my great joys. I love that there are always things which I do not know, things with which I’m unfamiliar and uncertain. This is where belief extends my horizons beyond what my knowledge can hold, a belief born from the optimistic twins of aspiration and imagination. I know that the essence of my being, the very fundamental elements of who I am, draw far more from these twins than any other emotion. I am what my dreams make of me, I see my world with eyes colored by what my mind imagines might be possible; and in that possibility I find the courage to hope for a better tomorrow.