Distractions – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

How distractions can be beneficial or detrimental, from a certain point of view.

On February 21st, a story appeared on the WBEZ Chicago website with reactions to Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker’s proposal to restrict cellphone use in all public and charter school classrooms. Mine was the first generation of students to have access to cellphones, and from day 1 it was a noticeable distraction for everyone in the room when someone brought their phone to class. Whether looking at the teacher who was trying to do their job in spite of a new topic to chide students over, or to the other students who see that one of their fellows is challenging the classroom’s authority so brazenly, to the student carrying the phone who now had a ready means of ignoring the teacher and missing out on the lesson, phone use is a problem for all.

In all honesty, I’ve been that student from time to time. In some classes it wasn’t a cellphone as much as it was a computer or a tablet that distracted me from the lesson or lecture at hand. In other cases, it was the unavoidable glow of the screen in the row in front of me shopping for shoes or looking at Spring Break trip ideas that drew my attention away from the topic at hand. Looking back, I recognize a noticeable drop in my attention and focus when these technologies began to enter the classroom, just as I notice now how I stopped reading nearly as many books once I discovered YouTube.

The idea of the distraction is often subjective; sure, in the classroom the student is supposed to be paying attention to the instructor, yet beyond that setting what are all the trappings of life but distractions from other facets which to varying degrees we ignore? This isn’t inherently a bad thing. Considering how troubled our times are fast becoming I have made a point of trying to find happy things to look at every day, and in some instances, I send these along to friends who I hope will benefit from smiling at something no matter how inconsequential.

In WBEZ’s report on student reactions to the Governor’s proposal to ban phones from classrooms the reactions were mixed. Some reactions speak to concerns about staying in touch with parents during the school day, especially in case of safety issues. I understand this point, it speaks to the reality that we’ve allowed ourselves to live in an increasingly dangerous society, and to that danger we need resources to mitigate it all while ignoring the underlying problems. We can distract ourselves from addressing gun violence, yet the shootings will continue all the same.

In my own experience the best classroom settings were those where the students either were mature enough to not pull their phones out in class or where they didn’t have their phones with them at all. In a recent substitute teaching job, I found that I was not only competing with student apathy toward following a sub’s instructions but that I also had to compete with students watching all manner of videos on their phones from Netflix and YouTube to TikTok, Instagram, and Snapchat. I simply can’t compete with these bright screens, and as most schools don’t inform their substitutes of any school policies (which allows students to abuse those policies when a sub is in the room), I’m at a tremendous disadvantage in that position.

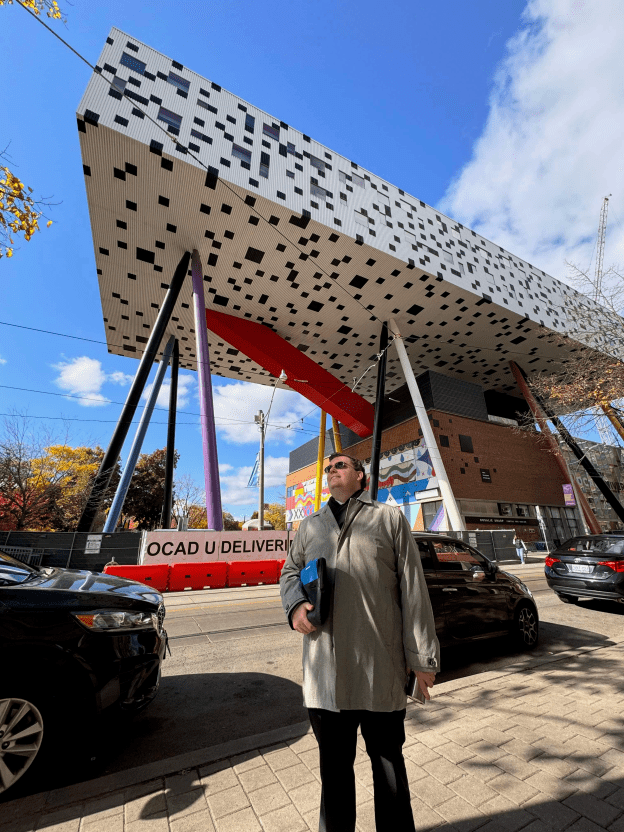

Today, as I write this blog post I have one conference presentation I need to write and an article submission that I need to revise. The former needs to be done in the next month and the latter by June 1st. In short: I have things I need to be doing right now, yet I can be more flexible with these extended deadlines and keep the Wednesday Blog going for another week. This publication of mine may seem like a sort of distraction to some of my colleagues, yet I feel it is a tremendous opportunity for me to write about topics that I have ideas about which my research doesn’t cover. After I write and record this blog post I will take full advantage of the good weather today (sunny with a high of 65ºF / 18ºC) and go for a long walk this afternoon. After that, I might look at these two projects again. As I said earlier in this paragraph: I have time to wait on both of them.

Returning to the topic at hand: whereas in my teenage years I found it empowering to have a school-issued laptop which I could use in class, today I yearn more for the days before that technology became so accessible to me for the sole reason that I could focus more on the moment at hand. Perhaps the greatest distraction that we’ve created for ourselves is our indefatigable busyness that keeps us moving at full speed whenever we’re awake. We fear boredom because we haven’t allowed ourselves to spend enough time surrounded by the silence that it brings. I wrote about this in October in the context of pauses in the dialogue of the Kate Winslet film Lee. I don’t know if I have any suggestions for systemic change this week, merely advice that each of us ought to look at what we think is most important for our lives and our enrichment. We only have so much time around, so the best thing we can do is to use it wisely.