On Writing – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

This week, some words about the art, and the craft, of writing.

In the last week I’ve been hard at work on what I hope is the last great effort toward completing my dissertation and earning my doctorate. Yet unlike so much of that work which currently stands at 102,803 words across 295 U.S. Letter sized pages inclusive of footnotes, front matter, and the rolling credits of my bibliography I am now sat at my desk day in and day out not writing but reading intently and thoroughly books that I’ve read before yet now find the need for a refresher on their arguments as they pertain to the subject of my dissertation: that André Thevet’s use of the French word sauvage, which can be translated into English as either savage or wild, is characteristic of the manner in which the French understood Brazil as the site of its first American colony and the Americas overall within the broader context of French conceptions of civility in the middle decades of the sixteenth century. I know, it’s a long sentence. Those of you listening may want to rewind a few seconds to hear that again. Those of you reading can do what my eyes do so often, darting back and forth between lines.

As I’ve undertaken this last great measure, I’ve dedicated myself almost entirely to completing it, clearing my calendar as much as I see reasonable to finish this job and move on with my life to what I am sure will be better days ahead. Still, I remain committed to exercising, usually 5 km walks around the neighborhood for an hour each morning, and the occasional break for my mind to think about the things I’ve read while I distract myself with something else. That distraction has truly been found on YouTube since I started high school and had a laptop of my own. This week, I was planning on writing a blog post which compared the way that my generation embraced the innovation of school-issued laptops in the classroom and the way that starting next month schools and universities across this country will be introducing artificial intelligence tools to classrooms. I see the benefits, and I see tremendous risks as well, yet I will save that for a lofty second half of this particular essay.

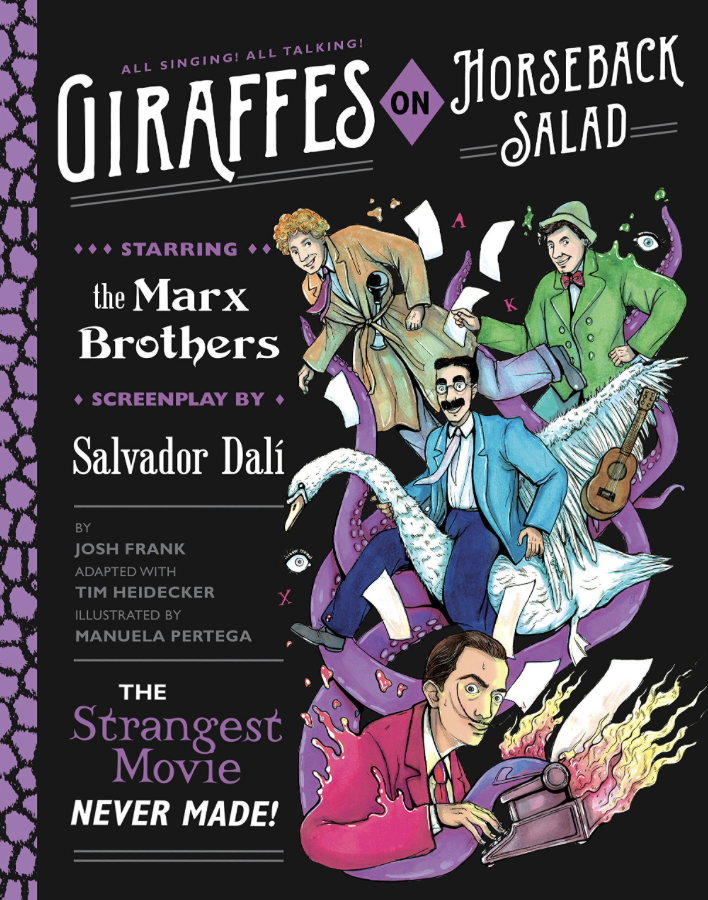

I’ve fairly well trained the YouTube algorithm to show me the sorts of videos that I tend to enjoy most. Opening it now I see a segment from this past weekend’s broadcast of CBS Sunday Morning, several tracks from classical music albums, a clip from the Marx Brothers’ film A Night at the Opera, the source of my favorite Halloween joke, and a variety of comic videos from Conan O’Brien Needs a Friend to old Whose Line is it Anyway clips. Further down are the documentary videos I enjoy from history, language, urbanist, and transportation YouTubers. Yet in the last week or so I’ve been seeing more short videos of a minute or less with clips from Steven Spielberg’s 2012 film Lincoln. I loved this film when I saw it that Thanksgiving at my local cinema. As longtime readers of the Wednesday Blog know, I like to call Mr. Lincoln my patron saint within the American civic religion. As a young boy in Illinois in the ‘90s, he was the hero from our state who saved the Union and led the fight to abolish slavery during the Civil War 130 years before. Now, 30 years later and 160 years out from that most horrific of American wars I decided to watch that film again for the first time in a decade. In fact, I’m writing this just after watching it so some of the inspiration from Mr. Lincoln’s lofty words performed by the great Daniel Day-Lewis might rub off on my writing just enough to make something inspirational this week before I return in the morning to my historiography reading.

Mr. Lincoln knew what every writer has ever known, that putting words to paper preserves them for longer than uttering even the longest string of syllables can last. What I mean to say is they’ll remember what you had to say longer if you write it down. He knew for a fact that the oft quoted and oft mocked maxim that the pen is mightier than the sword is the truth. After all, a sword can take a life, as so many have done down our history and into our deepest past to the proverbial Cain, yet pens give life to ideas that outlive any flesh and bone. I believe writing is the greatest human invention because it is the key to immortality. Through our writing generations from now people will seek to learn more about us in our moment in the long human story. I admit a certain boldness in my thinking about this, after all I’ve seen how the readership and listener numbers for the Wednesday Blog ebb and flow, and I know full well that there’s a good chance no one in the week I publish this will read it. Yet I hold out hope that someday there’ll be some graduate student looking for something to build a career on who might just stumble across my name in a seminar on a sunny afternoon and think “that sounds curious,” only to then find some old book of my essays called The Wednesday Blog and then that student will be reading these words.

I write because I want to be heard, yet I’ve lived long enough to know that it takes time for people to be willing to listen, that’s fair. I’ve got a growing stack of newspaper articles of the affairs of our time growing while my attention is drawn solely to my dissertation. I want, for instance, to read the work of New York Times reporters Patrick Kingsley, Ronen Bergman, and Natan Odenheimer in a lengthy and thorough piece on how Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu “prolonged the War in Gaza to stay in power” which was published last Friday.[1] I also want to read John McWhorter’s latest opinion column “It’s Time to Let Go of ‘African American’”; I’m always curious to read about suggestions in the realm of language.[2] Likewise there are sure to be fascinating and thoughtful arguments in the June 2025 issue of Commonweal Magazine, like the article titled “’The Living Vein of Compassion’: Immigration & the Catholic Church at this moment” by Bishop Mark Seitz, DD of the Diocese of El Paso.[3] I’m always curious to read what others are writing because often I’ll get ideas from what I read. There was a good while there at the start of this year when I was combing through the pages of Commonweal looking for short takes and articles which I could respond to with my own expertise here in the Wednesday Blog. By writing we build a conversation that spans geography and time alike. That’s the whole purpose of historiography, it’s more than just a literature review, though that’s often how I describe what I’m doing now to family and friends outside of my profession who may not be familiar with the word historiography or staireagrafaíocht as it is in Irish.

Historiography is writing about the history that’s already been written. It’s a required core introductory class for every graduate history program that I’m familiar with, I took that class four times between my undergraduate senior seminar (the Great Historians), our introductory Master’s seminar at UMKC (How to History I), and twice at Binghamton in courses titled Historiography and On History. The former at Binghamton was essentially the same as UMKC’s How to History I while the latter was taught by my first doctoral advisor and friend Dr. Richard Mackenney. He challenged us to read the older histories going back to Herodotus and consider what historians in the Middle Ages, Renaissance, Enlightenment, and Nineteenth Century had to say about our profession. Looking at it now, the final paper I wrote for On History was titled “Perspectives from Spain and Italy on the Discovery of the New World, 1492–1550.” I barely remember writing it because it was penned in March and April 2020 as our world collapsed under the awesome weight of the Coronavirus Pandemic. Looking through it, I see how the early stages of the pandemic limited what I could access for source material. For instance, rather than rely on an interlibrary loan copy of an English translation, perhaps even a more recent edition, of Edmundo O’Gorman’s The Invention of America, I instead was left working with the Spanish original that had been digitized at some point in the last couple decades. Likewise, I relied on books I had on hand in my Binghamton apartment, notably the three volumes of Fernand Braudel’s Civilization and Capitalism, in this case in their 1984 English translations. I wrote this paper and then forgot about it amid all the other things that were on my mind that Spring, only to now read it again. So, yes, I can say to the scared and lonely 27 year old who wrote this five years ago that someone did eventually read it after all.

What’s most delightful about reading this paper again is I’m reminded of when I first came across several names of fellow historians who I now know through professional conferences and have confided in for advice on my own career. The ideas first written in the isolation of lockdown have begun to bear fruit in the renewed interactions of my professional life half a decade later. What more will come of those same vines planted in solitude as this decade continues into its second half? Stretching that question further back in my life, I can marvel at the friendships I’ve cultivated with people I met in my first year of high school, now 18 years ago. That year, 2007, we began our education at St. James Academy where many of us were drawn to the promise of each student getting their own MacBook to work on. I wrote here in March 2024 about how having access to that technology changed my life forever.[4] So, in the last week when I read in one of my morning email newsletters from the papers about the soon-to-be introduction of artificial intelligence to classrooms across this country in much the same way that laptops in classrooms were heralded as the new great innovation in my youth I paused for a few moments longer before turning to my daily labor.

I remain committed to the belief that having access to a laptop was a benefit to my education; in many ways it played a significant role in shaping me into the person I am today. I wrote 14 plays on that laptop in my 4 years in high school, and many of my early essays to boot. I learned how to edit videos and audio and still use Apple products today because I was introduced to them at that early age. It helps that the Apple keyboard comes with easy ways to type accented characters like the fada in my name, Seán. Still, on a laptop I was able to write much the same that I had throughout my life to that point. I began learning to type when I was 3 years old and mastered the art in my middle school computer class. When I graduated onto my undergraduate studies though I found I could take notes far better that I could remember by hand than if I typed them. This is crucial to my story: the notes that I took in my Renaissance seminar at UMKC in Fall 2017 were written by hand, in French no less, and so when I was searching for a dissertation topic involving Renaissance natural history in August 2019, I remembered writing something about animals in that black notebook. Would I have remembered it so readily had I typed those notes out? After all, I couldn’t remember the title of that term paper I wrote for On History in April 2020 until I reopened the file just now.

Artificial intelligence is different than giving students access to laptops because unlike our MacBooks in 2007, A.I. can type for the student, not only through dictation but it can suggest a topic, a thesis, a structure, and supporting evidence all in one go. Such a mechanical suggestion is not inherently a suggestion of quality however, and here lies the problem. I’ve read a lot of student essays in the years I’ve been teaching, some good, some bad. Yet almost all of them were written in that student’s own voice. After a while the author’s voice becomes clear; with my current round of historiography reading, I’m delighting in finding that some of these historians who I know write in the same manner that they speak without different registers between the different formats. That authorial voice is more important than the thesis because it at least shows curiosity and the individual personality of the author can shine through the typeface’s uniformity. Artificial intelligence removes the sapiens from we Homo sapiens and leaves our pride in merely being the last survivor of our genus rather than being the ones who were thinkers who sought wisdom. Can an artificial intelligence develop wisdom? Certainly, it can read works of philosophy both illustrious and indescribably dull yet how well can it differentiate between those twin categories to give a fair and reasoned assessment of questions of wisdom?These are some of my concerns with artificial intelligence as it exists today in July 2025. I have equally pressing concerns that we’ve developed this wonderous new tool before addressing how it will impact our lived organic world through its environmental impact. With both of these concerns in mind I’ve chosen to refrain from using A.I. for the foreseeable future, a slight change in tone from the last time I wrote about it in theWednesday Blog on 7 June 2023.[5] I’m a historian first and foremost, yet I suspect based on the results when you search my name on Google or any other search engine that I am better known to the computer as a writer, and in that capacity I don’t want to see my voice as soft as it already is quieted further by the growing cacophony of computer-generated ideas that would make Aristophanes’ chorus of frogs croak. Today, that’s what I have to say.

[1] Patrick Kingsley, Ronen Bergman, and Natan Odenheimer, “How Netanyahu Prolonged the War in Gaza to Stay in Power,” The New York Times Magazine, (11 July 2025).

[2] John McWhorter, “It’s Time to Let Go of ‘African American’,” The New York Times, (10 July 2025).

[3] Bishop Mark J. Seitz, D.D., “The Living Vein of Compassion’: Immigration & the Catholic Church at this moment,” Commonweal Magazine, (June 2025), 26–32.

[4] “On Technology,” The Wednesday Blog 5.2.

[5] “Artificial Intelligence,” The Wednesday Blog 4.1.