Purgatorio – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

Last week, I wrote my thoughts on the first cantica of Dante’s Divine Comedy. This week then, the second part, the Purgatorio.

The sentiment of purgatory isn’t a good one, it’s a place where you don’t want to end up yet often find yourself stuck for longer periods of time. I often have dreams about needing to get somewhere or to do something or find something and getting stuck in an eternal loop of steps along the way and never actually reaching that goal. There are many different ways I could interpret those dreams of mine, yet in this instance I think they may be my subconscious imagination of purgatory.

Dante’s Purgatorio is an early depiction of this concept, though Jacques Le Goff (1924–2014), the French annaliste medieval historian wrote in the second appendix to his book The Birth of Purgatory that “the noun purgatorium was added to the vocabulary alongside the adjective purgatories.” In the next paragraph, Le Goff dated this addition to the decade between 1170 and 1180.[1] The concept itself is affirmed by the Catholic Church as doctrine today based on an interpretation of three verses from Chapter 12 of the Second Book of Maccabees, in which the author described how Judas Maccabaeus (d. 160 BCE) “exhorted the people to keep themselves free from sin, for they had seen with their own eyes what had happened because of the sin of those who had fallen.”[2] The footnote there in the New American Bible acknowledges that this passage “is the earliest statement of the doctrine that prayers and sacrifices for the dead are efficacious” and that “this belief is similar to, but not quite the same as, the Catholic doctrine of purgatory.” Dante’s depiction of purgatory fits well into this model, though he does write often of souls asking him to pray for them, as prayers for those in purgatory will speed their cleansing that they may enter Paradise again.

In this light, Dante’s purgatory is optimistic and hopeful. Sure, he encounters people who continue to suffer as they did in life from their own actions. In Canto 12, an angel proclaims to the poet and Virgil his guide, using Robin Kirkpatrick’s translation, “O human nature! You are born to fly! / Why fail and fall at, merely, puffs of wind?”[3] The cleansing path that the souls in this realm take requires tremendous effort and faith both in one’s abilities to surmount that path, and the reward for those efforts. Dante remarks later in Canto 12, “How different from the thoroughfares of Hell / are those through which we passed. For here with songs / we enter, there with fierce lamentations.”[4] The dead who walk the paths of purgatory then are working toward something, they know that they will learn in their paths the way into Paradise, it just may take a while.

The Purgatorio is remarkable for how it contrasts with the far more popular Inferno. Again, Dante stops and talks to everyone, and again nearly everyone he encounters is an Italian like him, someone with whom he can relate. He finds his fellow Tuscans among the crowds and makes his own birth well known by speaking Tuscan along his way. In several instances the souls he meets remark on the fact that he must be a Tuscan by his way of speaking, even if they themselves are Lombards, Latins, or from elsewhere.

I found it fascinating to see him encounter the ruling elite of Europe, the kings and popes who work off their sins. In one instance he sees Henry III of England (r. 1216–1272), one of my favorite medieval English kings, who had a pretty unfortunate and quite long reign. Dante places him among several other failed rulers, including Rudolf I of Germany (r. 1273–1291), Ottokar II of Bohemia (r. 1253–1278), Philip III of France (r. 1270–1285), Henry the Fat of Navarre (r. 1270–1274), Charles I of Naples (r. 1266–1285), and Peter III of Aragon (r. 1276–1285).[5] In Canto 20, Dante meets Hugh Capet (r. 987–996) who succeeded the last of the Carolingians as King of the Franks and founded the great medieval French royal dynasty which still exists as the Royal Family of Spain today. Capet sees his old life as something distant from himself:

“I was, down there, called Hugh Capet once.

From me were born those Louis and Philippes

by whom in these new days our France is ruled.

I was from Paris, and a butcher’s son.

And when the line of ancient kings died out ––

All gone, save only one who wears a monk’ dark cowl ––

I found my hands were tight around the reins

That govern in that realm, and so empowered

In making that new gain, with friends so full,

that, to the widowed crown my son’s own head

received advancement. And from him began

our lineage of consecrated bones.”[6]

In this world which he devised, Dante created tangible settings where the soul is cleansed after its life and before its final entry into Paradise. Dante himself climbed high until by the time he reached Canto 15, the suffering and toil of purgatory cleansed his own soul, so that in place of any other emotion “caritas burns brighter.”[7] The distinction in Latin between caritas and amor is something that I remember being discussed at length in my undergraduate theology classes at Rockhurst. These Latin terms are in turn translations of the Greek originals ἀγάπη and ερως, which I’ve come to understand as a distinction between charity and romance. The higher Dante and the penitents climbed up Mount Purgatory, the purer their souls became so that the affection they felt for their fellows and for all things was less a love that desired something of each other rather than a love that wished only to exist in communion with each other. In my fraternal order, the Ancient Order of Hibernians (AOH), our motto of “Friendship, Unity, and Christian Charity” speaks to this vision of love as charitable, unifying, and amicable. Purgatory was intended to replace fear and “penitential tears” with charitable love:

“If love, though, seeking for the utmost sphere,

should ever wrench your longings to the skies,

such fears would have no place within your breast.

For, there, the more we can speak of ‘ours’,

the more each one possesses of the good.

and, in that cloister, caritas burns brighter.”[8]

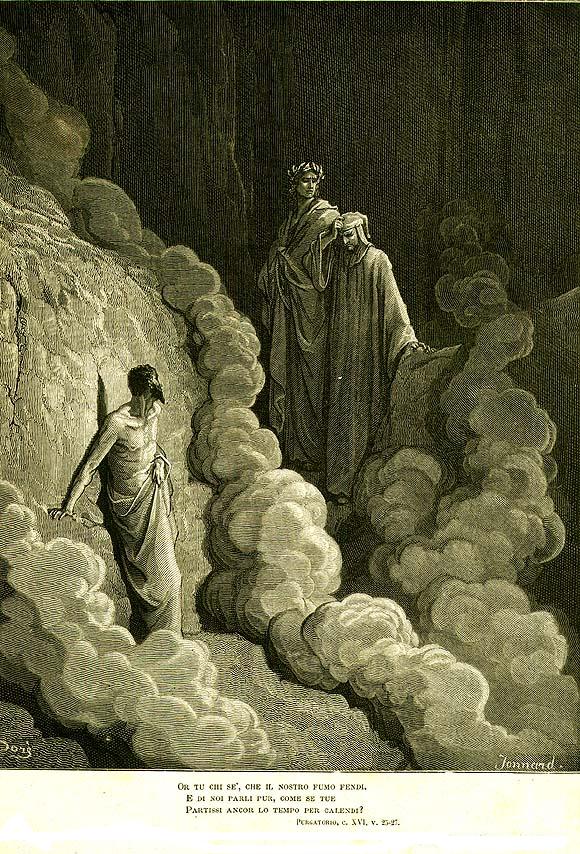

In purgatory, the penitents seek to cleanse themselves, and to cleanse the world in time as well. In Canto 16, the medieval Italian courtier Marco Lombardo remarked to Dante that societal corruption stems from the government:

“So — as you may well see — bad government

is why the world is so malignant now.

It’s not that nature is corrupt in you.”[9]

The hopes then of the penitent are that not only will they enter the Gates of Paradise but that all those who they left behind on the Earth will also join them and God among the heavenly spheres in their own time. Marco Lombardo remarked to Dante that “of better nature and of greater power / you are free subjects. And you have a mind / that planets cannot rule and stars concern.” In this, Marco reminds Dante that the key to Paradise is accepting one’s responsibility for one’s actions and life and being honest and free about one’s mistakes. Dante experiences this at the end of the Purgatorio, when he at last arrived in the Garden of Eden, located at the top of Mount Purgatory. There, he encounters his beloved Beatrice, the love of his life who sent the poet Virgil from the first circle of Hell (Limbo) to guide Dante to this point where he will at last be reunited with her.

Yet when Beatrice sees Dante standing there in the garden, she admonishes him for his sins and faults when she was alive and afterwards. She challenges him to be better, and to give up the last of his fear and worry, he had not come to her in the usual way after his own death. Beatrice challenged Dante, silencing him with sharp words that he did not expect of her:

“Respond to me. Your wretched memories

Have not been struck through yet by Lethe’s stream.”[10]

To advance further, and to be with his beloved again, Dante needed to forgo his feelings of fear and worry, remorse and sorrow, and instead embrace the moment in which he was living, standing there in her sight and hearing her voice.

“And yet –– so you may bear the proper shame

your error brings and, hearing, once again,

the siren call you may show greater strength ––

put to one side the seed that nurtures tears.”[11]

Beatrice is the first one in the entire Purgatorio who calls Dante by his name, the first to properly recognize him for who he is, more than just the wandering Tuscan poet or the Italian. I’ve often thought about how I would reveal characters’ names in my stories. I like to slowly peel away the layers of fog surrounding a narrative and let the audience discover the characters’ names in a more natural fashion. In a story I’ve begun to write, a sort of cleansing purgatory for the main character, his name is not uttered until after he has passed through these great circles of repentance in his own wandering way home.The Purgatorio concludes in a very mystical fashion, heralding the beginning of the Paradiso that follows. The symbols of the heavens abound, as Dante leaves fatherly Virgil behind to return to his own circle and follows instead his muse Beatrice toward the highest heights anyone in this cosmos can hope to achieve. That then, is where we will continue next week.

[1] Jacques Le Goff, The Birth of Purgatory, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984), 362.

[2] 2 Macabees 12:42–45 (NAB).

[3] Dante, Purgatorio 12.95–96.

[4] Dante, Purgatorio 12.112–114.

[5] Dante, Purgatorio 7.

[6] Dante, Purgatorio 20.49–60.

[7] Dante, Purgatorio 15.57.

[8] Dante, Purgatorio 15.52–57.

[9] Dante, Purgatorio 16.103-105.

[10] Dante, Purgatorio 31.11–12.

[11] Dante, Purgatorio 31.43–46.