The Art of Joy – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

This past weekend, the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art debuted a new retrospective exhibit on the life and work of Franco-American artist Niki de Saint Phalle. One of her great initiatives was to express rebellious joy in her art, especially later in her career.

I wasn’t familiar with the name Niki de Saint Phalle (1930-2002) before the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art announced they would be hosting the first American retrospective exhibition of her work, yet having seen aspects of it, particularly her Nanas, I find that I do remember seeing these around here and there. The exhibit begins with her early work, highlighting her tirs paintings (1961–63) which involved her shooting paint-filled collages of popular material objects each with their own cultural meanings, until they bled their paint out. I found these hard to appreciate, the violence at the core of these pieces and the claustrophobic nature of their assemblages filled me with a sense of dread.

Yet, it was the latter two thirds of the Saint Phalle exhibit which I returned to, the section radiating and erupting in light and color in a manner that felt welcoming and brilliant as though it were made to bathe in the warm rays of the Sun. These portions of the gallery were filled with her Nanas (1964–73) and other works in the same style. Saint Phalle created her Nanas as an evocation of the power of women, often drawing from ancient fertility figurines like the Venus of Willendorf, today housed at the Museum of Natural History in Vienna. Even the serpentine figures which I would normally be wary of felt warm and cheering.

So, what then is it about Saint Phalle’s work and this dramatic change between her early creations in the 1960s and 1970s to her later works in the 1980s, 1990s, and early 2000s that the latter ones feel so different? In my two visits thus far I’ve gotten a sense that early on she was fighting back against oppressive forces and that her resolve was to take hold of the ancient model of fighting violence with violence, while later once she felt liberated from these old shadows, as much as she could’ve been, she began to create in a spirit of wonderous joy.

I’ve had a hard time with joy lately, and I’m usually the eternal optimist. In many respects, I feel my emotions have had a softening in the last year and a half out of fatigue more than anything else. After I finished my teaching job in the Fall, I could not feel much for a good two weeks; I was so tired that Christmas came and went with only a passing acknowledgement from me. I gave every last drop of my enthusiasm and optimism in that job, knowing that I would have to do no less if I wanted to do that job justice. Joy then, the emotion that I felt even in the darkest and most terrifying days of the pandemic as I dreamed of better tomorrows, is something distant from me even now.

Yet I prefer to be optimistic, to live joyfully, rather than to be consumed by the trends of pessimism and destruction that are well in vogue now. There are horrific things happening in our world every single day, and I applaud those who are fighting to stop those horrors from spreading. The great fight of our time is one to defend democracy in a year when it is very well and truly under threat. It might seem naïve to some, yet I feel it is my vocation to try to keep a positive outlook and remind the people around me of all the good things we’re fighting for. What good is war if we give up any hope of finding peace again? Like Saint Phalle, I see joy in color and light. Where years ago, I would want to keep the shutters closed on my windows today I love having the sunlight dance between their opened gates and radiate an exuberance that reminds me of St. Francis wandering the fields around Assisi 800 years ago. There are great horrors in our world, and we need heroes who will face them and restore them to their box, yet we also need people to remind us of the good times so that we have a reason to envelop that darkness in light.

In the arts, the greatest periods in recent American history of optimism and joy are the New Deal and the Great Society, two moments when the political will to make life better for all Americans translated into an artistic awakening which sings the spirit of the times. The New Deal policies of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt responded to a time of great pessimism and trouble for America and the globe, when at the heart of the Great Depression he and his brain trust found ways to invigorate society through economic and financial reforms as well as new funds for the arts that had not been known at any time before. Here in Kansas City, we look to the paintings of our local artist Thomas Hart Benton (1889–1975) to evoke the regionalist style of the day, or nationally to the works of Georgia O’Keefe, Edward Hopper, and Grant Wood. I often associate O’Keefe’s art with the bright colors and lights of the desert Southwest, a region that was conquered by the United States from Mexico in 1848 yet not fully realized into our national mentality until after World War II.

For me, the great voice of this optimism is Aaron Copland, whose music evokes the same regional influences of the painters just mentioned. A long standing question in American classical music is how best do we define our national voice? I say we here because the compositions created in this country live or die by the audience’s appreciation. I found it fitting then when I read that the Kansas City Symphony’s first European tour, happening this August, will include performances of Copland’s Third Symphony in Berlin and Hamburg alongside performances of the works of three other great American composers: Bernstein, Gershwin, and Ives. In Copland’s music there’s a sense of the enduring youth of this country, the optimism of a new society building itself from these foundations.[1]

I love how the third symphony uses his famed Fanfare for the Common Man as a central theme, this idea that while in other countries fanfares would be reserved for only the great and the good descending down to our common level on their golden escalators, in our country that fanfare is open to anyone who is willing to live their best life. We are all capable of greatness as long as we live within that brilliant sunlight that so dominates the most optimistic periods in our art.

The greatest challenge that we humans have ever received is to love one another, to be kind and generous with our compassion, and to work for the betterment of all of us. I see that message fading somewhat today, its brilliance drowned in the neon glow of our own individualism and aspirations for fame and riches. It runs contrary to our culture as it has developed that we ought to prefer charity over transactionalism, that we ought to be kind to each other for no other reason than because it’s the right thing to do. I worry that this is lost amid all the revolving cycles of fads and trends that catch our attention for but a moment only to be overshadowed by the next.

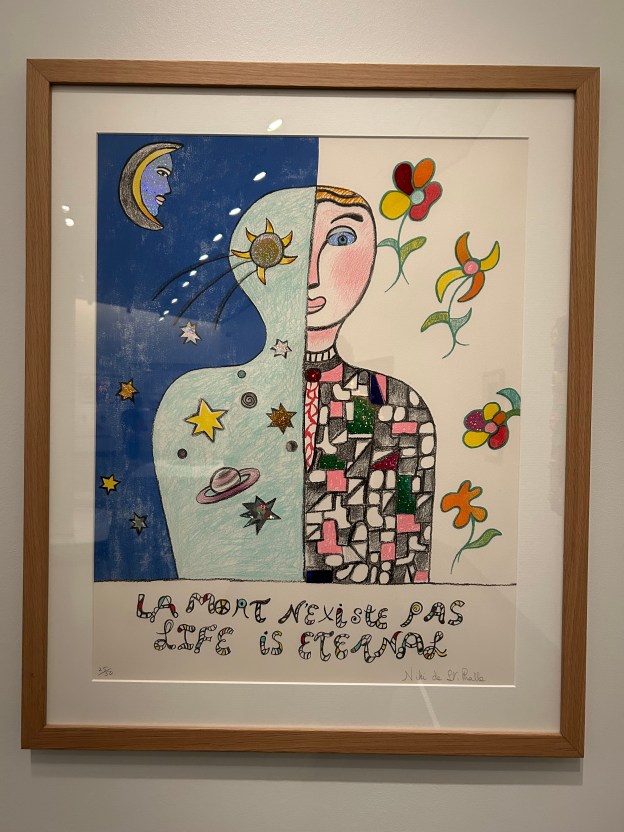

So then, perhaps what I appreciated the most about Niki de Saint Phalle’s later works was as much the longevity of their creation as it was their brilliant colors and joyous expressions. These are works which are meant to last so that generations of people will see them and perhaps in their forms feel a sense of their creator’s joy. I certainly felt that, even now 22 years after Saint Phalle’s death. I took one photo in the exhibit, of a color lithograph she made with a dualistic figure, on the one side with a human face and body and on the other the human frame surrounded by planets, moons, and stars. Beneath the dual figure Saint Phalle wrote in French and English, “La mort n’existe pas / Life is eternal.” I believe through our joy, no matter how childlike it may be, we can live on even after death. As St. Paul wrote, “Rejoice! Your kindness should be known to all.” (Phil. 4:4–9)

[1] Yes, there’s a great deal of problems with that new society’s foundations in the conquest and colonization of this continent.