The First Quarter-Century – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

This week, to begin Season 5, I discuss some hopes of mine for the first quarter of the twenty-first century through reflections on three things that I imagined might be possible twenty-five years ago.

25 years ago, I was a young boy of 7 when I witnessed the ringing in of the New Year 2000 in my Aunt Jennie’s living room. I was a new arrival here in Kansas City, having only lived here for close to six months, and surrounded by people and places that were fairly new to me. The end of the twentieth century was a significant turning point in my life. It meant that I would be a part of the first generation to grow to adulthood in the third millennium of the current era. Despite this I’ve always felt drawn to the 1990s as the decade when I planted my roots and began to seek out an understanding of my world and what might lie beyond.

I remember throughout the day sitting in front of the television set watching several things, including my first viewing of Star Trek: The Next Generation, whichever channel it was showed “The Best of Both Worlds” Parts 1 and 2. Yet they also cut to the new year’s celebrations in cities around our planet. I remember seeing the fireworks go off atop the Sydney Harbour Bridge and later along the Thames. At 11 pm our time we watched the ball drop in Times Square, and then again, an hour later the networks rebroadcast that ball drop for us living in the Central Time Zone. We stayed the night with my Aunt Jennie and cousins Chelsea and Isabella and then drove north to Smithville, Missouri on the morning of New Year’s Day to buy a new sofa before returning to the farm my parents bought the previous summer where we were still building our house. That winter we lived in a 10-foot long trailer that had to be moved into the farm’s barn in the winter to keep it from blowing over in the high winter winds. This way at least we could be on the build site so my parents could be around to oversee the entire process of our house being built. The only other thing of note from New Year’s 2000 was that it was the last time I visited the town of Smithville until February 2019 when I gave a public lecture at the Smithville branch of the Midcontinent Public Library system. I’ve since made the trip to that northern Kansas City suburb once more in April 2024 in a vain effort at seeing the Northern Lights when I could’ve stayed home and seen them perfectly well in the city.

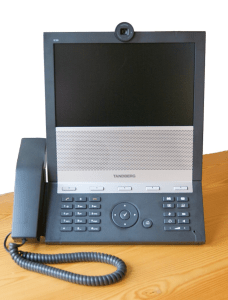

As New Year’s 2025 approached this year then I began to reflect on my memories of New Year’s 2000. In all honesty it was the first New Year’s that I can remember staying up for, let alone my first New Year’s in Kansas City. It’s one holiday that I’ve continuously celebrated in this city ever since. Yet what I’ve been thinking about more is what I was reading at the time about future technologies that were just around the corner. On a recent episode of the Startalk podcast hosted by Dr. Neil DeGrasse Tyson of the Hayden Planetarium in New York and Comedian Chuck Nice they interviewed Dr. Charles Liu, a professor of astrophysics at the City University of New York, Dr. Tyson talked about how the most futuristic thing that he looked forward to from the original 1960s Star Trek series were the videophones that they used. I too remember an entry in one of my childhood factbooks that I loved reading around the millennium which included one of these as one of the great up and coming technologies. While we may not have landline telephones with video capabilities like that entry suggested our portable smart phones all largely have this very function. The funny thing about it is that I rarely use FaceTime on my iPhone. Looking at my call logs the last FaceTime videocall I made was in March 2024 when I was excited to show off the room upgrade that I got in a hotel in the Chicago Loop to my parents. We’d stayed at that same hotel together several years before in the week between Christmas and New Year’s and had half the space for the three of us that I had in this room on my own.

I tend to make more videocalls on my computer over Zoom, FaceTime, WhatsApp, or Facebook Messenger and very rarely over Skype which Zoom largely replaced in 2020. Zoom has become the de facto videocall platform for many of us, especially in professional contexts. I even use Zoom to record lectures thanks to its screen sharing features. I do wish the technology could improve further though. It would be great to have an easier way to have the camera be set up higher so that it’s not looking up at me but instead straight-on or slightly downward. While an aesthetic preference it also speaks again to the old Star Trek ship-to-ship on screen communications seen in all of the series. Star Wars’s holographic communications would be an even neater step forward, and while I remember seeing a story about how the French left-wing leader Jean-Luc Mélenchon used holography in his bid in the 2022 French presidential election and another that ABBA is touring again in holographic form the technology still seems to be far from ubiquitous enough to be a regular form of communication.

Another technology that I remember dreaming about in 2000 that was in active commercial use then yet has lain dormant for most of the quarter-century since is supersonic flight. The Concorde last flew in 2003 thanks to its extreme cost and the fatal crash at Paris-Charles de Gaulle Airport in 2000. Yet I remember my Mom often saying that she wanted to cross the Atlantic at least once on a supersonic jet. While there are many aspects of the in-flight experience on your average transatlantic flight that I enjoy, I do actually enjoy the food and movies in economy for the most part, I certainly wouldn’t mind a quicker jump across the water to Europe. The average supersonic flight between New York and London or Paris was 3.5 hours compared to the 7 hours it tends to take on subsonic aircraft. That’s closer to the travel time for a flight from the Midwest to Southern California today. Looking at supersonic aviation now and the promises of companies like Boom at restoring supersonic flight to commercial service, I’m hopeful that I’ll be able to someday fly on one of these planes. In the short term I’m more hopeful that Kansas City might finally get a nonstop service to one of the European capitals in time for our hosting duties in the 2026 FIFA World Cup. On my last return trip from Paris to Kansas City via Washington-Dulles while I enjoyed a great many aspects of the flight I do remember a growing sense of annoyance at how long it takes to get to Kansas City from Europe when compared to most other American cities our size and larger.

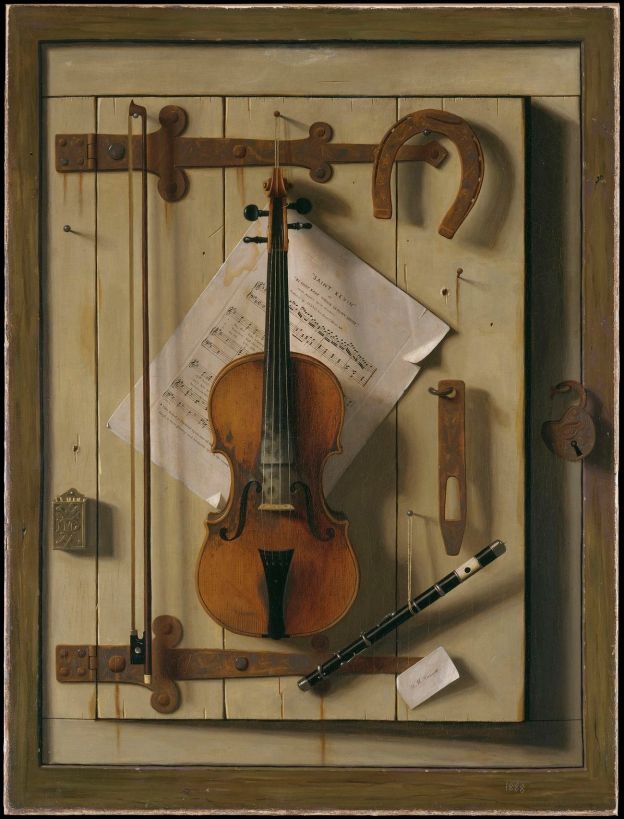

Finally, at the turn of the millennium one of my favorite TV shows was the natural history program Eyewitness co-produced by the publisher Doring Kindersley, Oregon Public Broadcasting, and the BBC. Surprisingly for how influential it’s been, I haven’t written about Eyewitness on the Wednesday Blog yet. This program brought the factual book series of the same to life for its viewers and set the stories of life, the universe, and everything it told in a computer-generated space it called the “Eyewitness Museum” which acted in some ways like a physical museum yet in many others with unusual camera angles and hallways it was entirely an edifice of the mind. I remember loving this series because it gave me the space to imagine and wonder at nature, the world, and human history in a manner which few other programs have done. I remember hoping that I could visit such a museum sometime in my life, and in some ways I’ve done that time and again. Many of the cultural artifacts in the program are on display at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, and when it comes to the animals & plants on camera it’s well and truly on display in natural history museums around the globe that I’ve gotten to visit.

I rediscovered Eyewitness again in my early twenties when DK began uploading the episodes onto YouTube. By that point I’d already been making videos of my own for nearly a decade, and rewatching this old show from the ‘90s I was inspired to try to frame the material I wanted to describe in videos and in my teaching in a similar minimalist fashion on a blank white background with the object of my videos and lectures taking front and center. As it turns out, white is a much harder color on the eyes so in 2019 I switched to a light blue which I continue to use. My former students will certainly be quite familiar with my blue slideshows that form the core of my teaching materials. Those old Eyewitness episodes disappeared from YouTube in Fall 2023, in fact the last time I watched any of them was when I showed one to my seventh graders as part of their World Geography class.

Yet when thinking about the Eyewitness Museum itself the technology exists today that the viewer could tour that structure through virtual reality headsets. I still haven’t tried one of those on yet, at first from what I understood they didn’t fit over glasses, yet I’m curious about what potential they may hold for both education and entertainment. It would be fascinating to use such a headset to wander through that labyrinth of galleries famous for their all-white surfaces and see everything they hold.The last twenty-five years did not meet our expectations in many respects. Paul Krugman’s final editorial for the New York Times published on 9 December 2024 speaks to the loss of our millennial optimism in the face of 9/11, the Wars in Afghanistan & Iraq, the Great Recession, and all the other crises that have crashed on the rocky shores of our world. Where for a while we thought we might have fine sandy beaches that heralded a prosperous, safe, and happy future now we have fearsome cliffs which act as much as walls defending our “scepter’d isles” as limits to the possibilities of things in our world. I feel a dissonance in my own life with the world we live in because I am still an optimist, and still dream of things that we could do, new monuments to that optimism we could build, and like the Irish quarrymen brought to a young Kansas City in the nineteenth century by Fr. Bernard Donnelly, the founder of the Kansas City Irish community, ways in which we can break down those cliffs and build a city of fountains and gardens in its place. I’ll write more about all of this next week in a reflection on what I hope we will see realized in the next quarter of the twenty-first century. By the time we reach New Year’s 2050, I will be 57 years old, far from the young boy who watched humanity ring in the third millennium in what was for him a new city in a new time full of hope.