On Language Acquisition – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

This week, how living in a culture is required to speak a language in depth.

The languages which I speak are directly responsible for the ways my life has turned, its winding path a result of the words I use and the ideas they represent. Language is the voice of culture; it evokes the rich harmony of thought that comes from seeing things from certain points of view. At the University of Westminster, I was regularly in classes where there were maybe 10 or 20 languages spoken between each of the students, if not more. English remained our common language and the language of instruction, yet how many of us must have been switching between English and their own native language as they thought about the readings and topics in political philosophy and science which we discussed on a given day? Even then, my English is not the same as the King’s English, nor is it the same as the English I heard spoken when I drove through Alabama in July 2022. Language then reflects our individual circumstances of experience. Knowledge is gained through experience first and foremost, whether that experience be theoretical through books or practical through lived experience. I make this distinction because I often feel that when I’m reading a particularly well written book that I can actually imagine the characters as real people who I might meet in my life. The best TV shows and films are like that, their casts that we see regularly begin to seem like old friends who we look forward to visiting again and again.

Language acquisition is a lot like this for me. Today, I speak three languages: English, Irish, and French, and I can read Latin, Italian, Catalan, Spanish, and Portuguese and some Ancient Greek. I break my languages down into these two categories by their utility in my life. The handful which I can read are those which I’ve worked with in my historical capacity. I’ve spoken Italian and Spanish from time to time, yet those moments of elocution are few and far between. The same could be said for my German, though it’s now been five years since I last spoke that language in Munich, and at time of writing I can’t say that I’d be much use in remembering it today. This is even more true for my Mandarin, a language which I studied for a semester in between my two master’s degrees out of pure curiosity. I can remember the pronouns, a couple of verbs, and a noun or two but that’s about it. All this to say that I may know something about German and Mandarin yet it’s little more than a foundation for the future when I might be faced with a desire or need to learn the language properly.

I’ve been thinking lately that of any of these I need to work most on my Spanish, the most useful of these languages for me to speak here in the United States. I can understand Spanish fine yet speaking it remains a challenge. On Sunday evening after my shift I decided to reopen the Spanish course on the app Busuu––one which I used for Spanish before my March 2023 trip to the Renaissance Society of America’s annual meeting in San Juan, Puerto Rico––and try it out again.[1] That time I got through the A1 level before life got in the way, and I gave it up feeling frustrated with the process. I did not resume any online Spanish courses before my trip to Mexico last November for the History of Science Society meeting in Mérida, instead choosing the less preparatory method of winging it.[2] That worked with fits and spurts, my best Spanish conversations were in taxis with locals, though I was mostly thinking about how I would say things in French and then Hispanifying them based on my minimal knowledge of Spanish grammar. On Sunday, after I retired for the evening from my Spanish lessons on the app I realized what it was I missed so much in these apps: the human connection. Busuu prides itself on its crowd-sourced learning method; throughout the course learners are asked to submit spoken or written answers to the computer’s prompts which learners of other languages who speak the target language then correct. I like this system overall, and it does give this sense of community, yet I feel that it could go further.

After English, the second language I learned was Irish, my ancestral language. I started studying the Irish language when I was fourteen and have been focused on it to varying degrees for the last eighteen years. It really took until 2022 for me to connect with the language though, in spite of the fitful starts and stops because in that year I began to build a community around the Irish language. First on Zoom through Gaelchultúr, an Irish language school in Dublin, I met other speakers from across North America and beyond who like me were descendants of Irish immigrants old and new. I looked forward to seeing some of the same people term after term. Yet after returning to Kansas City, I began to look locally for Irish classes and came across the community that my friend Erin Hartnett has built at the Kansas City Irish Center. Through Erin I’ve met some really good friends and from our mutual appreciation for our ancestral language we’ve found a lot more in common from mutual histories to mutual appreciations for rugby. Without this community I would speak Irish but not terribly well. Now, not only do I speak Irish daily, but I also write in Irish every day. It has truly surpassed French as my second language, something I’m proud of yet not too concerned about when it comes to my Francophonic abilities.

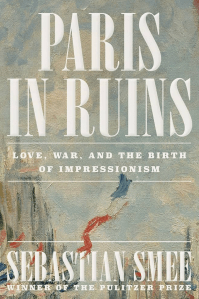

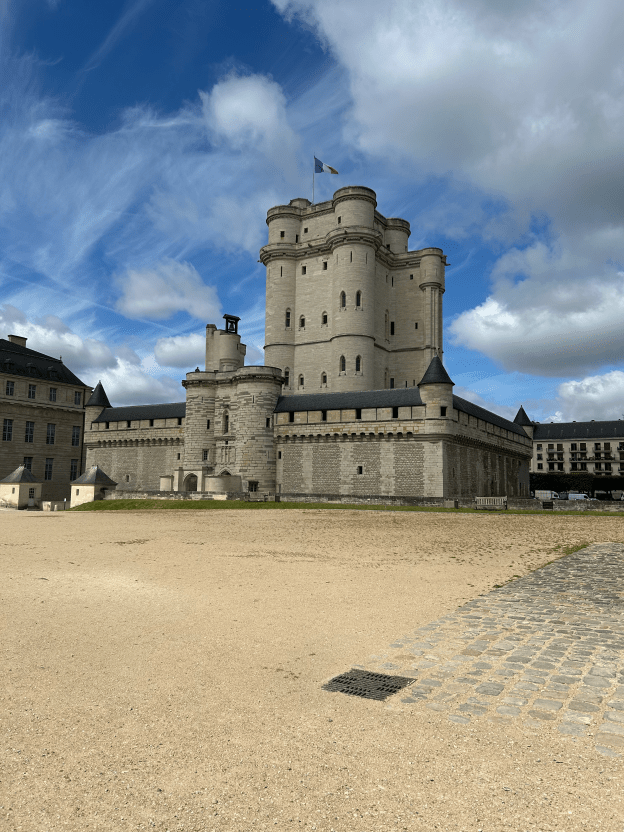

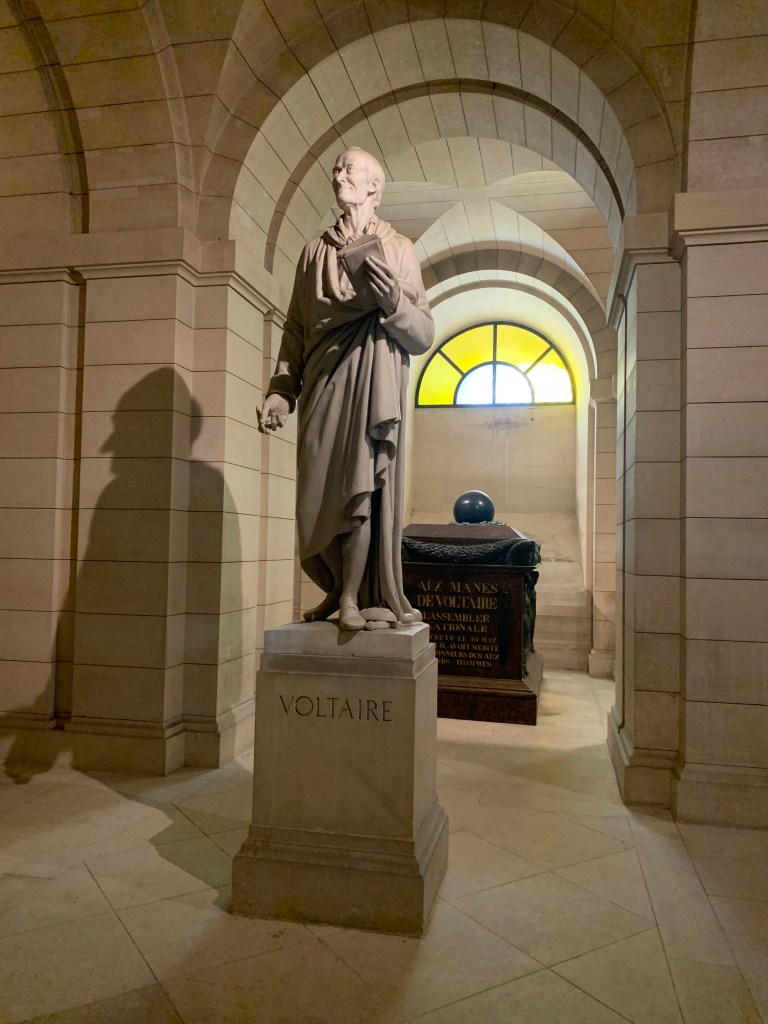

French exists in a different sort of place for me than Irish. It’s not an ancestral language with deep family ties. Rather, it’s a language that I gravitated toward out of a fascination with French culture and history. I may have written here in the Wednesday Blog before that my first exposure to French came at sunset on a Sunday in February 2001 when my Mom put a “Learn French” cassette tape into the tape player in our family car when we were driving through the hills of northwestern Illinois toward Dubuque, Iowa. She and I were preparing for a trip to London and Paris that summer, the first European trip that I could remember, and she wanted to put in the effort for us to have some French before we arrived on the Eurostar from Waterloo Station at Paris-Gare du Nord. I didn’t like Paris much on that first visit, I found the language barrier to be too great for me to really feel a sense of connection with the place. On my next visit to France in March 2016 with three years of undergraduate French under my belt I found that I not only got the place more, but I appreciated the nuances of French culture more than I had as a child.

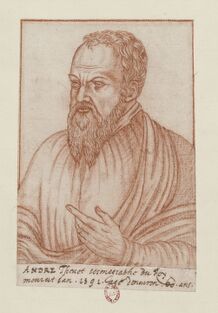

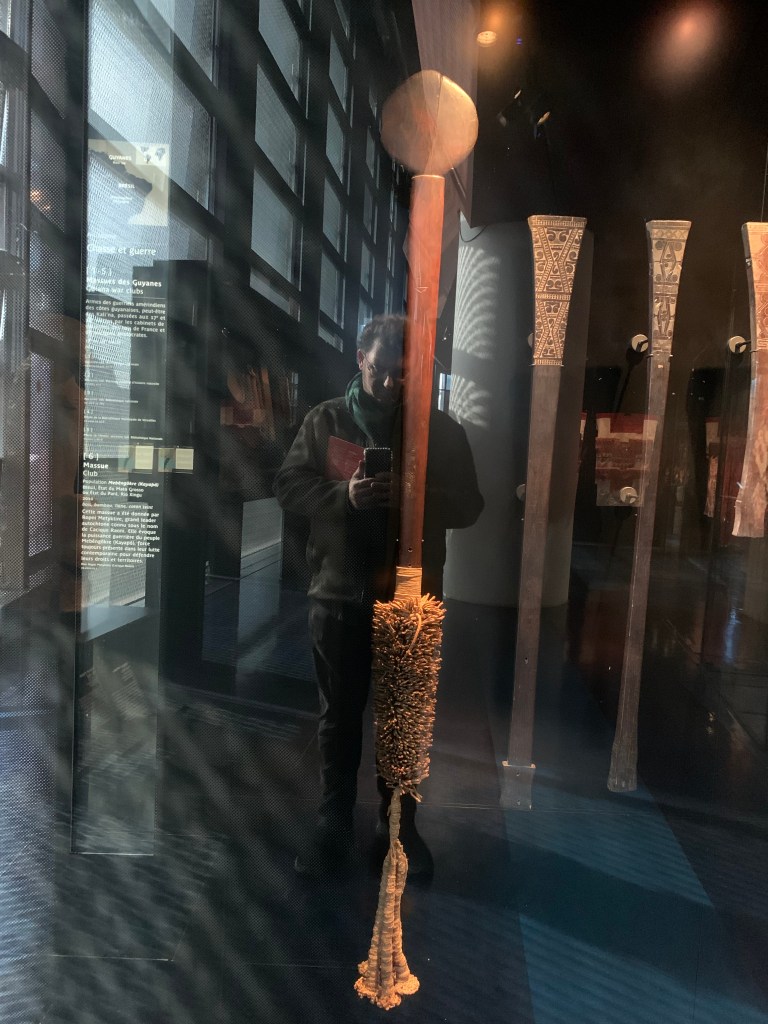

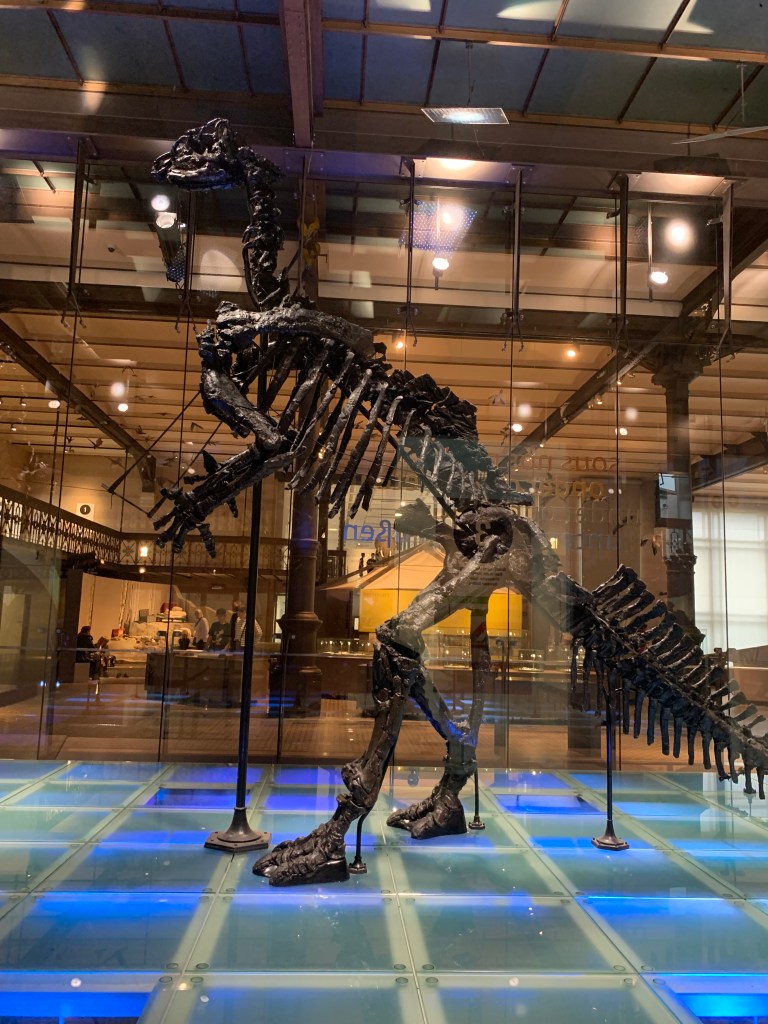

I owe a great deal to my undergraduate French professors M. Kathleen Madigan and Claudine Evans. It’s through their classes that I gravitated toward my career studying the French Renaissance. When I get asked why I chose to study the French I keep it simple and say it was a matter of pure convenience: I already spoke French, so I wouldn’t need to learn a new language (Spanish or Portuguese) to read my primary sources. That’s how I ended up studying André Thevet (1516–1590). I chose him because he happened to write about a sloth and for me the idea of being a sloth historian made me laugh. It’s as simple as that. I loved studying French in college, and even more teaching it with the online Beginner French course I built for the Barstow School in 2023 and 2024. I found that going through the same textbook I used a decade before I was not only teaching the students who in the future would go through my course, I was also renewing my own French education and learning things that I’d missed on my first go around. This is a critical point in language acquisition: few people are going to get a language on their first try, it’ll take multiple goes to understand what’s being said and to make oneself heard as well. It took me three tries to get Irish down, and the same is the case for Latin. Failure in the moment is merely a setback which can, and ought to be overcome in future endeavors. After all, remember that if we’re paying attention to our lives we’ll learn from our experiences.

I grew to really embrace a lot about the Francophonie to the point of paying Sling TV for access to TV5 Monde, France’s global TV channel which now broadcasts several different channels. I personally enjoy TV5 Monde Style, which tends to broadcast documentaries and cooking shows, though I don’t watch it as much as I might like. I read a lot of French books for my research, after all I work with source material that has largely only been written about in French and to a lesser extent in Portuguese. I am able to do what I do with those sources because I can read them and the secondary literature about them in French. All this made it all the easier for me to go to France and Belgium in the last several years and be able to switch from English to French as soon as I walked off the plane. I found when I was flying back to the United States in June 2024 after spending about a week speaking mostly French in Paris that I was consistently responding with the quick phrases “please, thank you, you’re welcome,” and the like bilingually with the French followed by the English as I’d heard so many people do in shops and the museums during that visit. It took me a while to get past doing this and just say things in English again after I returned.This then is why I think I’ve had so much trouble with learning Spanish. It’s the first language that I’ve given a big effort to learning outside of a classroom on my own. At least in the classroom you have fellow students around you to practice with. When you’re on your own you’re on your own, a wise-sounding craic which is to say that when alone you have no one else to talk with. I have friends here in Kansas City who speak Spanish, and I know all I have to do is ask, yet it’s finding the free time to sit down with them and work on it that I need to figure out. To truly gain a footing in a language one needs to immerse oneself in the culture. Apps and online learning will only take you so far. A classroom learner will blend into their own classroom idiolect of the language in that particular space where it exists in their life. Only if they move beyond classroom and begin to converse and live with people in places where that language is spoken will they begin to speak it in a manner which is more recognizable to native speakers.

[1] “A Letter from San Juan,” Wednesday Blog 3.29.

[2] “The North American Tour,” Wednesday Blog 5.34.