How to Know the Unknown – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

This week I want to talk about how we can recognize the existence of unknown things.

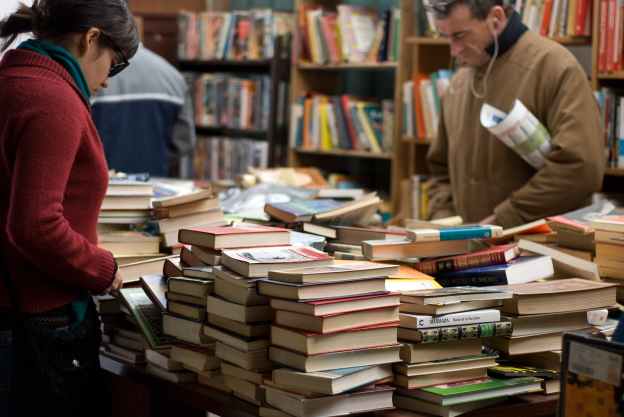

At the beginning of the month when I was preparing for my copyright post, I looked into an old interest of mine that had always been there, yet wasn’t quite active in the last few years, the effort by an organization called Thank You Walt Disney to restore the building that his first studio, Laugh-O-Gram, occupied at 31st & Forest here in Kansas City called the McConahay Building. To this end, I made a detour by the old building one afternoon on the way back from the central post office at Union Station and saw a good deal of work underway on that block, and after some back and forth I found a book written by some members of that organization called Walt Disney’s Missouri that I requested from the Kansas City Public Library.

I found Disney’s early years in Marceline, Chicago, and Kansas City quite familiar; his passion and drive to create art and tell stories in a new and inventive way using the skills and talents he developed over those early years remind me deeply of many of the ideas and projects I’ve worked on since my high school days. The sky truly is the limit in this mindset. I find the young Walt Disney to be a familiar face, someone who is quite relatable to all of us who have adopted Kansas City as our canvas for the many things we create.

Yet Kansas City is not like many other great American cities, for unlike New York, Los Angeles, or even Chicago we aren’t on a shoreline, we don’t look out onto an endless expanse of water far out to the horizon. Instead, we have the vast sightlines of the prairies and Great Plains extending out from our city in every direction. The astounding sunsets that glowed across the prairies out to the west of our old family farm are some of the great images of my childhood that will forever be burned into my memory.

When I was reading about Disney returning to Marceline, Missouri as an older man, I felt intensely familiar with the setting having grown up in the Midwest; familiar with the vast scale of the prairie that overwhelms me in how small it makes me, and the few built-up edifices of our civilization feel amid the tall grass Prairie. Our interventions only emptied this landscape and rebuilt it anew with the farms & ranches that have largely replaced the native roots. We have changed this landscape to suit ourselves, and yet this landscape remains its own because its fundamental character is too distinct for us to fully comprehend in our vision of a normal inspired by the great woodlands and old colonies of the East Coast and even older cultivated and measured forests and farmland growing around the ancient generational villages and towns of Europe.

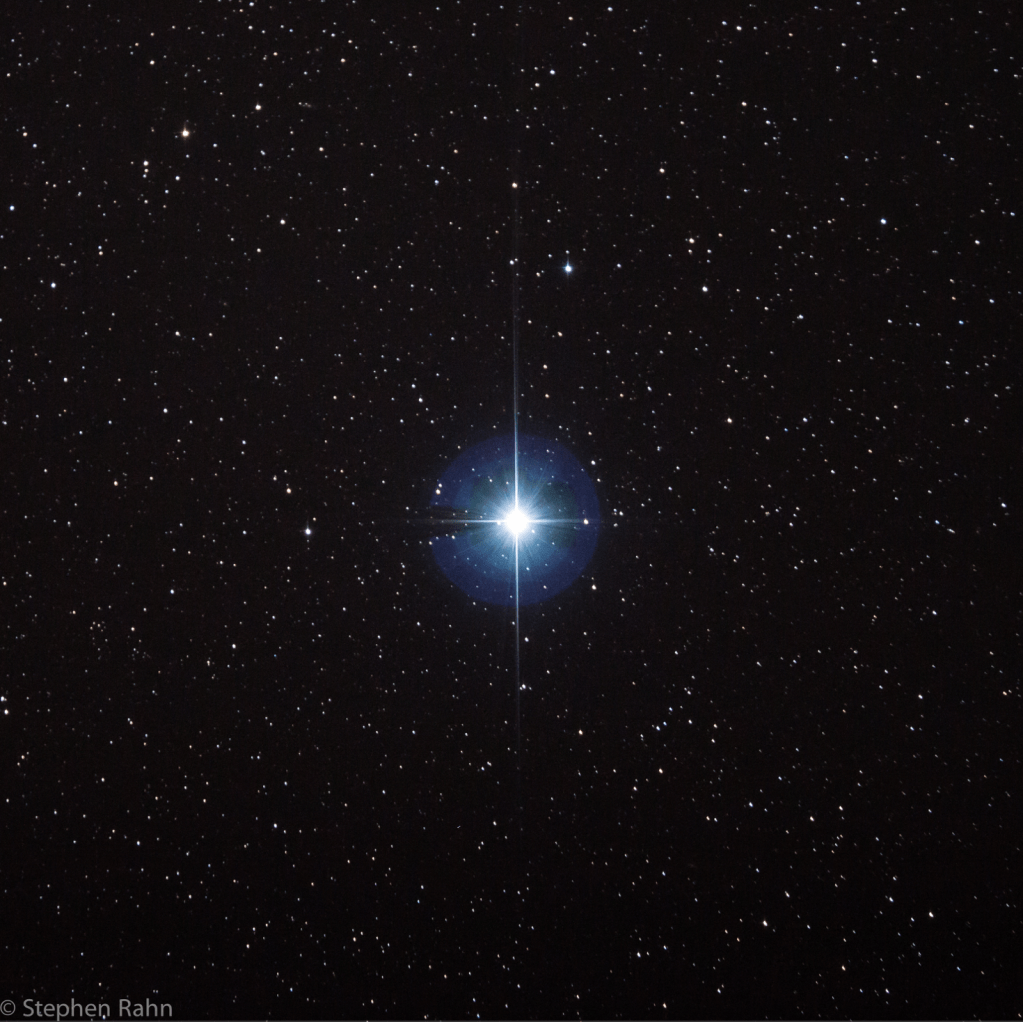

My research focuses on the unknown entities that were too far-fetched to be imagined on the edge of the European imagination, particularly animals whose proportions were exaggerated to a degree that set them and the world they inhabited apart from the well-known and measured Mediterranean World at the heart of the European cosmos. This question of how we can begin to describe the unknown has stood out to me for a while and it’s something that both thrills and scares me at the same time. I feel a profound sense of humility thinking of all the things that we don’t know that exist beyond our world, whether they be lifeforms deep in the still largely unexplored oceans or entities deep in the void of Space. Yet I love stopping to think of these things and the endless horizon they represent as it gives me a sense of things still to accomplish.

Imagine, dear reader if you will, what it would be like to witness something you never before knew appear before your own eyes, or even those things which you do know about but only in stories and fables happening in real life. Shakespeare asked his audience to use their imaginations to fill in the breadth and depth of his world. In the prologue of Henry V, the Chorus asks the audience to imagine that the actors on the stage might

“on this unworthy scaffold bring forth

so great an object. Can this cockpit hold

the vasty fields of France? Or may we cram

within this wooden O the very casques

that did affright the air at Agincourt?

O pardon, since a crooked figure may

attest in little place a million,

and let us, ciphers to this great account,

on your imaginary forces work.

Suppose within the girdle of these walls

Are now confined two mighty monarchies,

Whose high upreared and abutting fronts

the perilous narrow ocean parts asunder.”

Henry V, Prologue 11–23

Our imaginations are perhaps our greatest assets, after all we call ourselves Homo sapiens, wise humans. We pride ourselves on our capacity for thought, on our ability to imagine possibilities for ourselves and our posterity. We need the unknown to give us hope that there will be something new to discover tomorrow, for even if that new thing is familiar to others, it will still invoke wonder in us. Hope is what the greatest human endeavors are built upon, the hope that even if a cause seems doomed in the short term that someday it will succeed.

I feel this sense of potential success is central to my nature. I grew up with this hopeful maxim from three sources, my Catholic faith in things inexplicable, my Irish heritage informed by the experiences of generations who hoped for home rule and justice under a colonial government, and more light-heartedly from my lifelong passion for the erstwhile lovable losers, the Chicago Cubs. Robert Emmet perhaps put it best in his speech from the dock that he knew someday his epitaph would be written, someday someone yet unknown to him in 1803 would be able to judge his efforts towards Irish independence. “Let my character and my motives repose in obscurity and peace, till other times and other men can do them justice. Then shall my character be vindicated; then may my epitaph be written.”

We cannot truly know what our future will hold, though we can predict what variable futures might come to exist. I wonder if a young Walt Disney would have imagined the man he would become, and how his name would be known by what surely is a majority of humanity alive today, 123 years after his birth. All of that was unknown in his childhood, just as all the things that will happen tomorrow and every day after that are still to a certain degree unknown to us today. That might be the closest we come to touch the unknown, to recognize its ambiguous feel, yet while that fine cloth of silk might seem somewhat familiar in its unfamiliarity, we ought to always remember that it extends far enough from our view and beyond all our horizons into infinity. There is, and likely will always be, more unknowns than knowns in the Cosmos.

A historian restores things forgotten from the vast silk threads of the unknown and weaves those fibers back into the great tapestry of human knowledge. I just started reading a book yesterday which does this with the understanding that religion and science have always been at odds when it comes to the age of the Earth. Perhaps I will write about that book, Ivano Del Prete’s On the Edge of Eternity: The Antiquity of the Earth in Medieval & Early Modern Europe in this publication later this year. That, good people, remains well and truly among those strands of the great yet smooth silky unknown sea which lies behind us, beyond our vision as the Greeks understood the future to be. The future is perhaps more unknown to us than the past because we at least have means and methods to uncover the past we’ve long forgotten and left behind, whereas the future remains unwritten and daunting to behold.

Perhaps that is why I chose to become a historian, because I find a comfort in imagining and reading about the past that is absent when I imagine the future. There is some truth there that the future I behold is colored in the same hues as my present, which I know will not be realized as the future will certainly be its own creation, inspired by our current moment yet distinct from it all the same. The characters who grace this “kingdom for a stage” will have taken their last bow by the time many of these events I imagine in the future occur; and at the culmination of the future lies the greatest unknown of all, one about which we tell many stories and ascribe many tenants, all to humanize it and make it more familiar.Our memories keep past ideas, people, places, and things alive in our knowledge. I hope the people at Thank You Walt Disney are successful in restoring the McConahay Building which housed Disney’s Laugh-O-Gram Studio so that the memory of that time when so many creative minds, so many animators, lived in this city is preserved; so that Kansas Citians in the present and unknown future remember that art can be created here, and dreams first imagined here can grow into wonders for all humanity to behold.