Click the Instagram logo above to view my archived Instagram story from this trip.

Introduction

The morning after our stargazing, my Dad and I packed up our belongings and took our places in the Mazda for the 170 mile drive west to Salt Lake City. I was feeling exceptionally better after the visit to the Vernal Urgent Care the day before, the medicines they’d prescribed turned out to do the trick of minimizing my sneezing from a rate of one sneeze a minute to more like one sneeze every thirty minutes. Still, as we left the dusty streets of Vernal, I couldn’t help but feel like we were moving out into a place that’d be even more unfamiliar to me.

The Salt Lake Valley isn’t the biggest metropolitan area between the Rockies and the Sierras, that’d be Phoenix, but it certainly holds its own weight as a major cultural and economic center for the region. The gravitational pull of Salt Lake could be felt throughout our time in Utah, it is to the Beehive State what New York City is to the Empire State, though I admit I never heard any Utahns call it “the City” like New Yorkers tend to do. We made our way west along US-40 across the Uinta Basin out of Vernal towards the Uintah and Ouray Reservation, home to the Northern Ute, and the Wasatch Range beyond.

The landscape remained very dry, brownish in color, and was marked by scrub bushes and other smaller foliage, sparsely placed to use as little water as possible in such a dry place. The American West is in the middle of what’s been called a megadrought, meaning that water levels throughout that half of the continent are well below where they normally should be, and have been for years now. While there weren’t signs nexts to the sinks in our hotel rooms advising us to use less water like I’ve seen before in California, the low water levels in some of the reservoirs that we passed were worrying signs of the impacts that the changing climate has already had on life in that region.

As we made our way further west, the landscape began to become mountainous again. Unlike the Front Range on the outskirts of Denver and Colorado Springs, the Wasatch Range that splits the great population centers of the Salt Lake Valley with the rural landscape of the Uinta Basin to the east pose a tremendous barrier to travel and development. I knew that Salt Lake sat in a valley between two mountain ranges, but was totally unprepared for the extreme difference in altitude that we ended up experiencing as we drove into Park City and closer towards Parleys Canyon, the pass through which I-80 enters the Salt Lake Valley.

Salt Lake City

The first I think I’d ever heard about Salt Lake, or Utah in general, was as a young Bulls fan in the late 1990s when the Utah Jazz were frequent NBA Finals rivals of my hometown team. Later, in 2002, I got to see a lot more of Salt Lake and Utah during the Winter Olympics that were held in that city, but beyond sport I frankly didn’t know nearly as much about the Beehive State as I did about its eastern neighbor Colorado. In more recent memory, Real Salt Lake, Utah’s MLS team, has been a consistent rival for Sporting Kansas City, even playing against Sporting in the MLS Cup back in 2013, and when Kansas City’s women’s soccer team’s ownership group fell apart in 2017, the NWSL moved the franchise out to Utah where they became the Utah Royals. Only this year, 2021, did that franchise get moved back to Kansas City following ownership issues in Salt Lake.

Knowing about the region’s sporting credits may provide one sense of local awareness, but in any city it can never provide the full picture. Salt Lake however isn’t any regular city. As the home of the the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (the LDS or Mormon Church), Salt Lake is also tremendously important within that world, something I was keenly aware of as we arrived in that valley and first caught sight of the skyscrapers of its downtown core, soaring high above the Mormons’ holiest spot, Temple Square.

I’d booked us into a brand new Courtyard hotel in the suburb of Cottonwood Heights to the southeast of downtown. While the Vernal hotel turned out to be a step nicer than the Denver one, this hotel was substantially nicer than either of those. Primarily built as a hotel for the ski resorts in the neighborhood, the building was practically deserted when we got there on that afternoon in early June. Unlike the far higher 14ers of the Colorado Rockies, there wasn’t any snow left atop the highest peaks of the Wasatch Range. Instead of winter sports, most people who we encountered on the trip seemed, like us, to be traveling for the sake of travel itself, to get out of the house after a year of pandemic shutdowns and quarantines.

Over the previous year, as I’d planned out the still nigh mythical Great Western Tour, I’d also found other ways of getting that travel itch taken care of, through travel shows on TV and regular videos about all sorts of things on YouTube from the parts of the country I wanted to visit. In particular, in the last few years I’ve been a frequent viewer company profile and business history videos from channels like CNBC. One of these was for the Southern California burger chain, In-n-Out, which I’d discovered had expanded beyond the Sierras into, among other cities, Salt Lake.

As funny as it sounds, one of my goals of the trip was to have at least one meal at In-n-Out, to try and redeem the chain after my admittedly poor experience having lunch at one of their San Francisco locations back in 2016. Once we’d moved our luggage into the hotel room, I suggested lunch to my Dad, noting that there was an In-n-Out only a few minutes drive from there. He agreed with the idea and we got back into the car and drove deeper into the suburban sprawl. I have to say as good as the food was, I was shocked at how affordable it all was. We’ll see how far east that chain expands in the long run, I’d be happy to have one or two here in Kansas City eventually.

We spent most of the first afternoon in Salt Lake there in the hotel. I needed to do laundry, and we were both tired of driving. Plus, with a US men’s soccer match against Costa Rica that afternoon, I was hoping to spend at least part of the day watching the contest on ESPN. Our second big foray from the hotel that day was for dinner, which ended up taking us past two completely full restaurants before we found a Persian restaurant in a strip mall nearby, our first time trying that country’s cuisine. It turned out to be a wonderful meal, spent in a relatively quiet restaurant far from the busy tourist destinations near the ski slopes.

That evening, while I had hoped I might watch some local TV, I ended up spending most of the time reading, studying if you will, for the next day’s adventures. We’d planned on going into Downtown Salt Lake, in particular visiting Temple Square, and I didn’t feel comfortable doing so without at least some basic knowledge about Mormonism and the history of the LDS Church in Utah.

This is by no means an exhaustive study of Mormonism, or anything of the sort, but as best as I was able to make sense of it, the Latter-day Saints, as they prefer to be called, see their church as the fulfillment of Christianity through the aid of modern prophets in a tradition begun in the early nineteenth century Great Awakening with Joseph Smith (1805–1844), their founder. The LDS often found the communities where they settled in the East and Midwest to be unwelcoming to them, the Governor of Missouri even called up the militia to drive the LDS from the state. As a result, they continued westward until arriving in the Salt Lake Valley under the leadership of Smith’s successor, Brigham Young (1801–1877). This has led to Utah in general but Salt Lake in particular having a very distinct culture compared to the rest of the West, with the region around I-15 in and surrounding Utah being frequently called the Mormon Corridor.

Coming from a Catholic background, the best analogy I could think of for understanding the significance of the Salt Lake Temple and Temple Square surrounding it is the Vatican, as it is both the spiritual and administrative heart of their church, and more generally their world. There’s an old idea, one which I actually study, that American things are somehow more juvenile than Old World things. You can hear it in Churchill’s famous “We shall fight them on the beaches” speech, with the “New World coming to the rescue of the Old.” I think at its core, the fact that our societies as they exist today in the Americas are quite new settler colonial societies does feed into this idea, but by extension it’s meant that American things, New World things, often have been looked down upon in a Eurocentric perspective.

As a Catholic, a member of a very Old World form of Christianity, this is certainly something that makes sense in considering some of the reasons why Mormonism has been so badly looked down upon in general by the rest of society in the United States. That said, Christianity in this country is a complicated mix of old world churches, Catholicism, Lutheranism, and Orthodoxy in particular (immigrant churches) standing alongside those Protestant churches, the Episcopalians, the Methodists, the UCC, the Baptists, and the AME Church, that have roots in Europe, largely in Britain, but have been so thoroughly Americanized in the centuries since independence as to be equally foreign to their European counterparts. In this mix stands the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, a church born in the United States that grew up on the frontier of American society, a community that’s always been a bit of an odd one out alongside its peers.

We drove into Downtown Salt Lake, and after finding parking, made our way up to Temple Square. Unfortunately, the complex was under extensive seismic renovations to ensure the buildings’ stability up to a 7.3 earthquake on the Richter scale. Nevertheless, we were able to walk around the outside of the complex and find an open footpath leading to the courtyard in front of the Temple, where we were able to stop and look at the building up close. Purported to be based in design after Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem, it’s an impressive building, clad in quartz monzonite, its spires seem to represent the permanence of the LDS in Utah. Near the Temple stands another building of immense significance in the history of silent film, the old Hotel Utah, now the Joseph Smith Memorial Building, where in late 1920 Charlie Chaplin completed cutting his classic film The Kid. He had to smuggle the reels out of California where his first wife was demanding them as her property in their divorce trial.

From Temple Square we returned to the car and left the Salt Lake Valley for the Utah Olympic Center high up in the Wasatch Range over Park City. The center, home to a number of ski slopes, as well as a few ski jumps that lead in the summer months into a swimming pool well placed on the edge of a cliff, hosts two museums in its visitors center. On the lower level is a museum dedicated to skiing in Utah, while the upper level hosts a nostalgia-trip of a museum holding relics of the 2002 Winter Olympics. While I enjoyed seeing the ski stuff on the lower level, not being a skier myself I found it less engaging than the Olympic memorabilia on the upper level.

The Salt Lake Olympics were the first winter games I can remember watching nearly in full. There was something about them being in the US, even if they were over a thousand miles away in a state I’d at that time never been to, that made those games feel like they were on my own home turf. It was especially interesting to me seeing how the uniforms and sportswear has changed over the years, how the speed skaters’ garb has become even more aerodynamic, allowing for today’s skaters to beat the records of 20 years ago time and again, or how much the US hockey sweaters haven’t changed all that much, the same old trusty look for the same old team that as long as I’ve been watching can beat the Russians but always seems to come up short against the Canadians. Ugh, Canada.

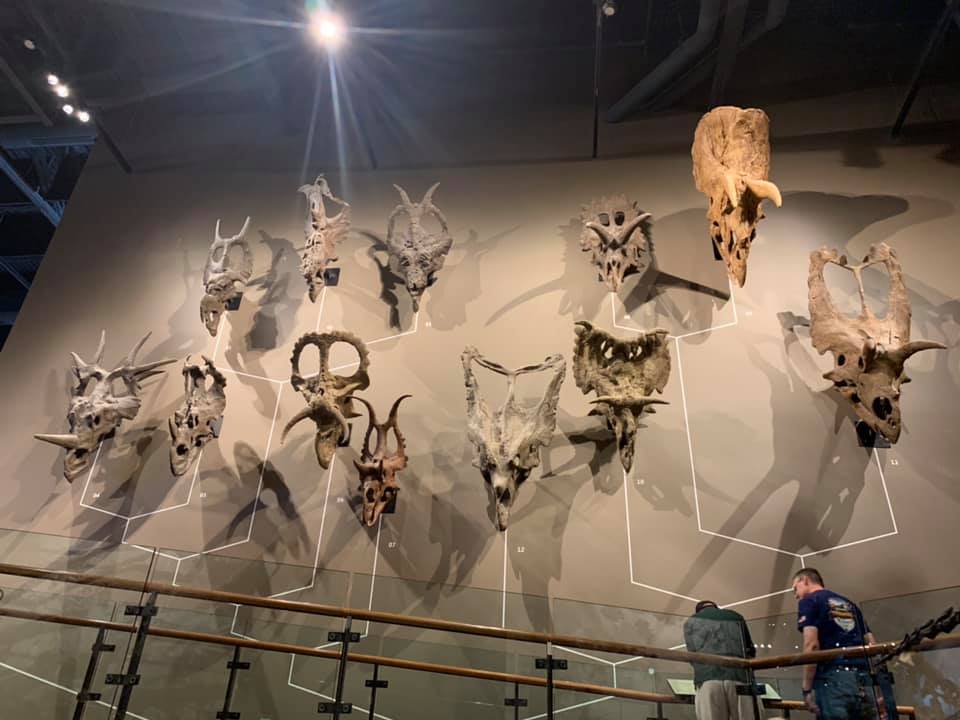

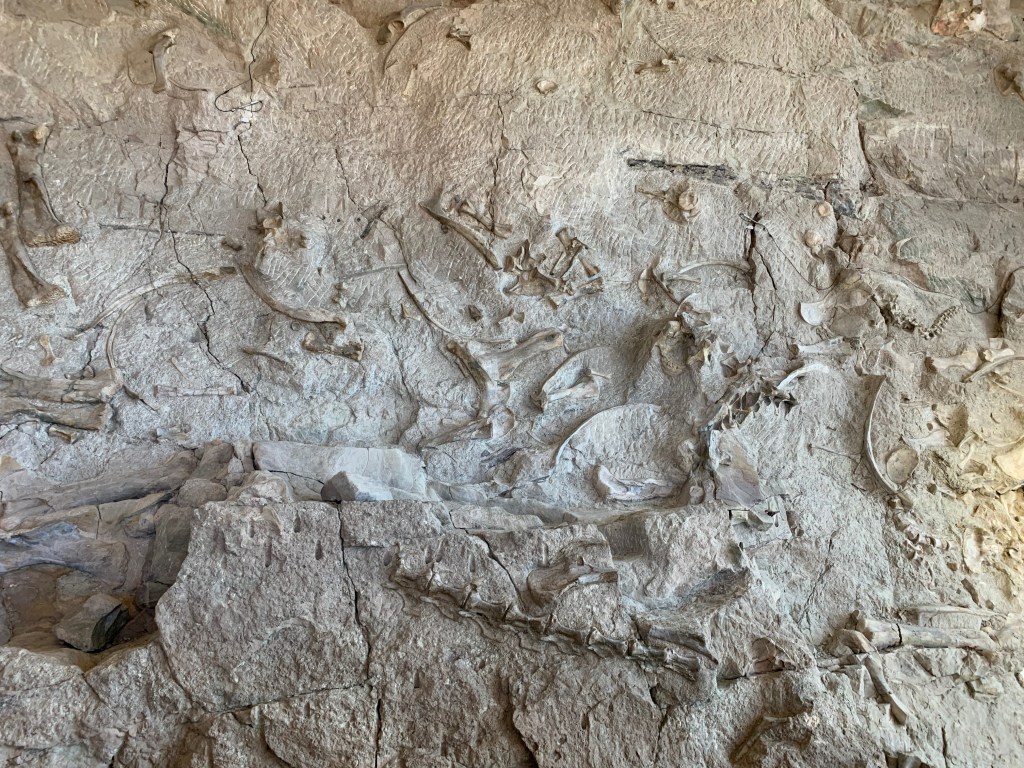

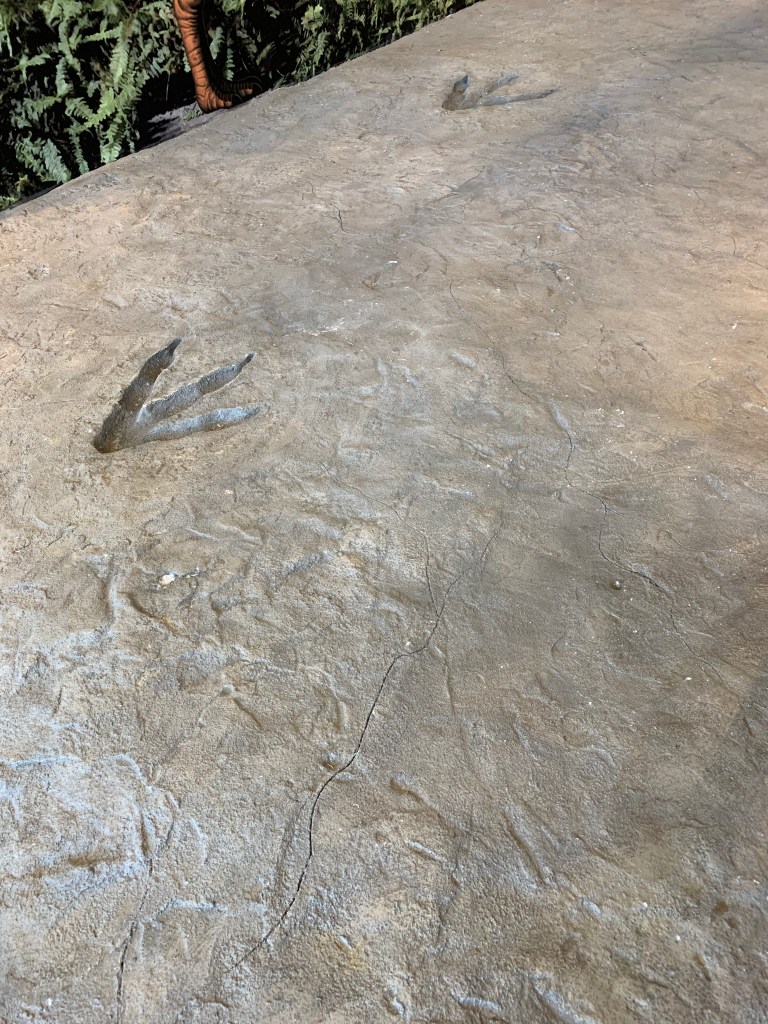

From the Olympic Center we returned to the Salt Lake Valley and drove to the campus of the University of Utah, where we made a stop at the Natural History Museum of Utah in the 10 year old Rio Tinto Center. Of the natural history museums I’ve visited here in the US, this one in Salt Lake has proved to be the most forward thinking in the way they display their exhibits, owing in large part to the youth of their building. The building itself reminded me a bit of the newer sections of the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, which opened to the public in 2007. In terms of the exhibits themselves, I was especially impressed by how regional in focus they were. Sure, you had your dinosaur highlights, your Tyrannosaurus Rex and your Triceratops, but so many of the fossils on display were less famous dinosaurs that were quarried in Utah, itself one of the great fossil states. On top of this, the museum dedicated an entire floor of exhibit space to Utah’s native peoples, the Shoshone, the Goshute, the Ute, the Paiute, and the Navajo.

Leaving the museum, on my Mom’s suggestion, we drove west across the valley to the Great Salt Lake itself. She told us there was a Great Salt Lake Visitors’ Center that we could stop at that’d tell us more about the lake itself, and after a drive we came to a building that looked like it might be a visitors’ center. As it turned out, we’d stopped at the Saltair concert venue, a little ways to the east of the visitors’ center, but while parked there, we left the car and walked a half-mile out onto the dried lake bed until we reached the salty water. I was surprised at the strong smell of the salt lake, which frankly wasn’t something I should’ve been surprised by, after all it is a salt lake, and should smell of salt. From the water we walked back to the Mazda and made our way westward along lakefront, figuring we’d run into a visitors’ center eventually, that or we’d start rounding the lake. Once we did find the visitors’ center, we were surprised to find how close we’d actually gotten to it on foot.

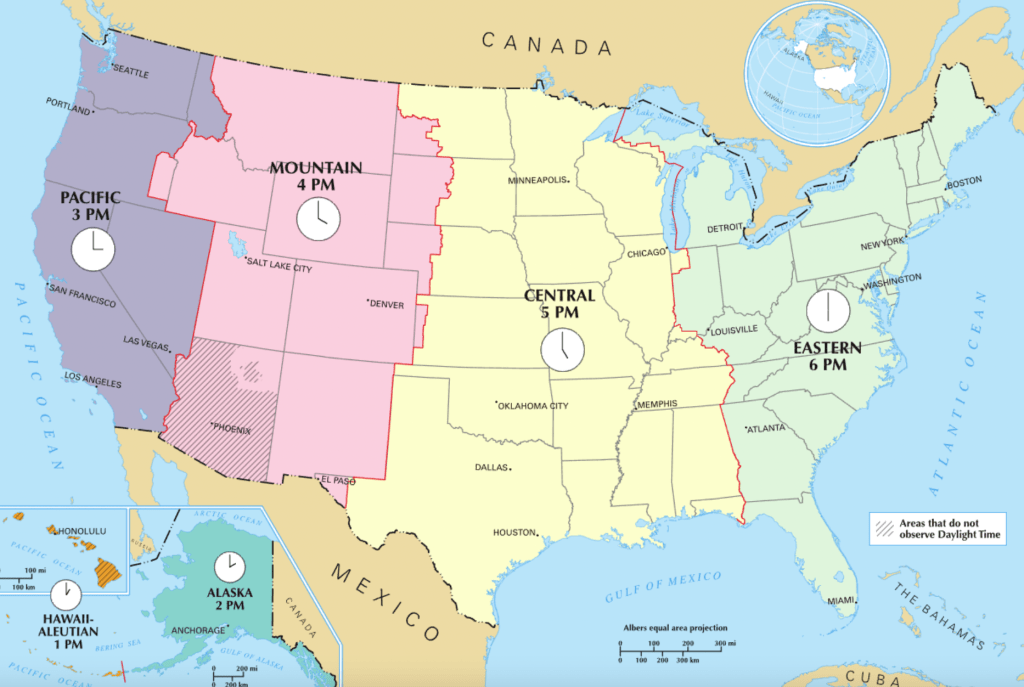

By that point, sunset was coming fast, and we decided to head back to the hotel and figure out the next day’s drive from Salt Lake to Grand Junction. As tough as the last two longer drives had been, no matter which route we took on this one it’d be harder than anything else we’d done yet. By interstate, Salt Lake and Grand Junction are connected by I-15 and I-70. This involves a 110 mile stretch of I-70 in south-central Utah without any services, and while the Mazda can usually travel around 300 to 320 miles on a tank of gas, the idea of driving so far without places to stop or people who could help should we break down gave us pause. The other route was I-15 to Provo and then US-6 diagonally southeast toward Green River, Utah. This route would be quicker, and go through more towns with gas stations and other services, but it involved a 120 stretch of winding mountain highway that has been called one of the most dangerous in the United States. Naturally then, we chose the second route.

All things were going well for the first part of the drive until we left I-15 in Provo and made our way into the mountains on US-6. It was as we were passing through Spanish Fork, a pass in the Wasatch Range, that we began to see the emergency UTDOT signs warning that US-6 was closed ahead due to a wildfire. The megadrought was a big part of the cause, as was a lightning strike more particularly. I suggested we turn around and head back to I-15, take the long way around on the interstate and trust that we’d have the foresight to not run out of fuel in that 110 stretch of highway without services. Dad, who was driving, decided to keep going ahead, and soon we made it to the detour around the fire, which took us and countless semis, RVs, and other vacationers onto a winding backroad that was hardly wider than a cowpath. This continued for a good eight miles, until we came to a backup just beneath the place where the fire itself was burning on the mountainside. We waited for a good 20 minutes as the northbound traffic cleared, before we continued on our way out of harm’s way and toward I-70.

The Deserts and the Plateaus

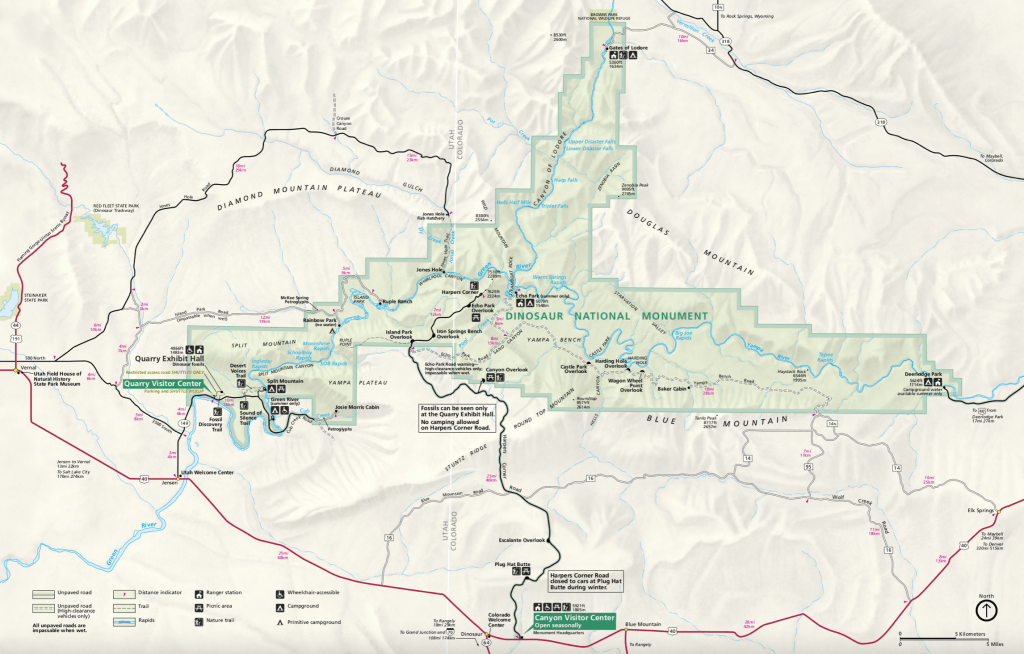

While we’d spent a fair amount of time in the high deserts around Vernal, that didn’t compare to the far harsher deserts around the Utah crossroads town of Green River. Situated on I-70 at the intersection with US-6 and US-191, Green River seems a bit of a misnomer for a town in such a dry place as this. And yet, through it flows the Green River itself, the great lifeblood of eastern Utah, over whose banks further upstream we’d spent an evening stargazing in Dinosaur National Monument just earlier that week.

Typically in a river system, the longer river will bear the more prominent name. This is why we usually talk about the Mississippi River Basin rather than the Ohio or Arkansas River Basin, or why the Green River is usually seen as a tributary of the Colorado River which flows from the Colorado Rockies down through the deserts and canyons of the Intermountain West until what’s left of it after thousands of miles of dams and agriculture trickles into the Gulf of California on the eastern side of the Baja California peninsula. That said, hydrologically the Green River is longer than the Colorado River, it just happens that because of some politicking by an early 20th century congressman from Colorado’s western slope that the then named Grand River was renamed the Colorado River and recognized as the main river of that drainage basin. Naturally the congressional delegations from Utah and Wyoming objected.

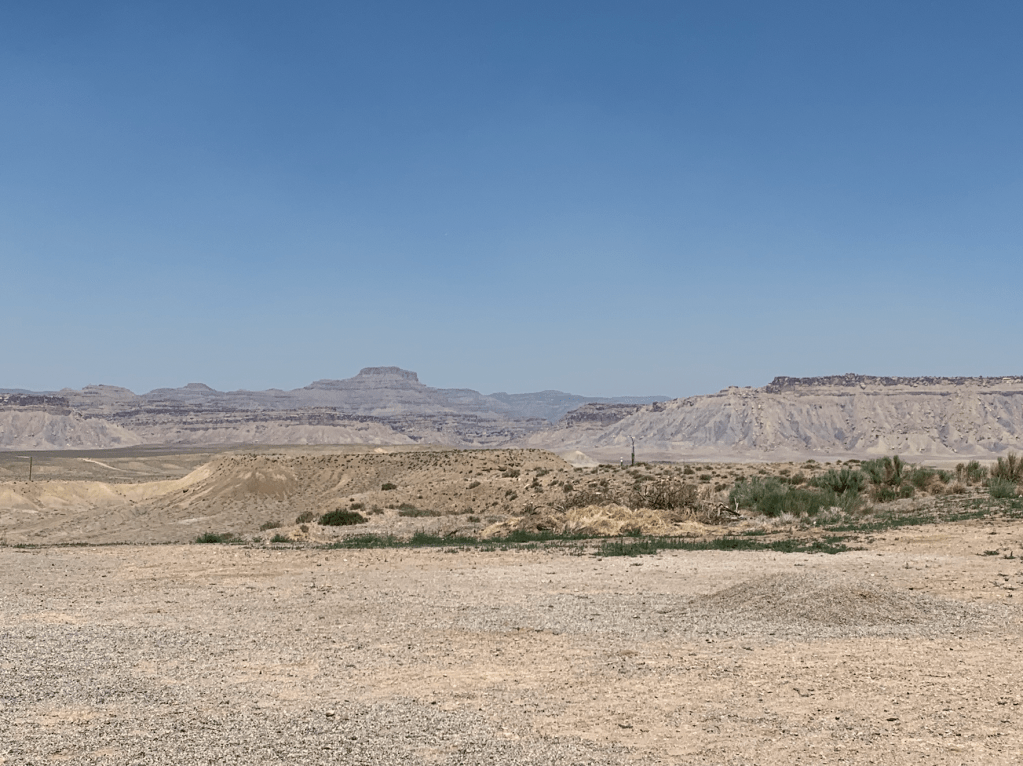

As we drove along I-70 across Utah, the landscape changed from a scene of brown soil and low shrubs to one of yellowish white sandy ground, with little to no greenery around, the desert as one might romantically imagine it. We stopped after a while at a rest area at the top of a hill, and took a few minutes to experience the environment, the atmosphere of this most alien of settings for us. Coming from the Midwest, the usual color palette that nature provides us is filled with greens and brightly colored flowers. Kansas City is a metropolis set on the prairie but filled with trees. In contrast to this, the desert we now crossed seemed harsh to our eyes, yet at the same time there was an element of beauty to it all the same.

With a higher speed limit of 80 mph, we quickly made our way across Utah and back into Colorado, the Welcome to Colorful Colorado sign a welcome sight and a reminder of what one might call familiar ground closer to home. We were still west of the Rockies, in a part of the state that neither of us knew terribly well; still a good four hours drive away from the familiar confines of metropolitan Denver. The Colorado border quickly brought our next stop onto the horizon, Colorado National Monument.

A series of canyons, buttes, and mesas to the south of Grand Junction, Colorado National Monument is quite easily the most impressive natural site we visited on this trip. Established as a national monument by President Taft in 1911, the main road leading through it, the aptly named Rimrock Road, was carved into the landscape in the 1930s as a New Deal project. That 24 mile stretch of pavement proves to be one of the most scenic of scenic routes we could’ve ever taken to get to a hotel, and well worth the extra night on the drive east. The views reminded me of the prologue scene from Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, or any number of other movies or shows set at the turn of the last century, when the West was just beginning to be incorporated into the tourist’s America.

At the monument’s main visitors’ center we stopped and went for a mile hike out on the cliff edge, stopping at various points to look over the precipice at the deep canyon below. Years ago, my parents had bought a photo print of Colorado National Monument with the mesas to the north behind Grand Junction. That image had been up on the wall for most of my life, first in their house in Wheaton, then on the farm in Kansas City, KS, and now in their current house in Kansas City, MO. Only recently had it come down for whatever reason, yet as we made our way through that monument, we kept looking for that view that was in the picture. Surely it’d be out there somewhere. Whether we found it or not remains to be seen, but certainly of the places we’ve visited on this trip, Colorado National Monument will be one that we’ll return to.

The High Rockies

We considered going back up the switchbacks into the monument that evening to give the stargazing a second go, but ultimately decided against it, instead choosing to go find dinner. The next morning came quickly, and after some time watching the Saturday morning shows on CBS, we returned to I-70 and continued the journey eastward back into the Rockies. Denver is nominally only about 4.5 hours east of Grand Junction, but for drivers like us who are less used to that sort of terrain, we ended up taking far longer to get to that evening’s destination. It wasn’t for any poor traffic or poor navigating on our part, but rather for the fact that we had one last day left on the trip and wanted to use it as best we could.

I’d been thinking for a while that a neat way to cap this particular western tour would be a drive up to the top of Mt. Evans, whose summit boasts the highest paved road in the United States at 14,271 ft (4350 m). We’d driven up it once before in 2005, arriving at the summit in the middle of an afternoon thunderstorm, but hadn’t made a return visit since. That said, when I looked at road conditions that morning, I found that entry passes to the road had been fully booked for the day, and so spent the first two hours of the drive trying to come up with another detour, one that would provide the adventure we were looking for.

Leaving the deserts of the western slope, we soon entered the narrow winding course of the Glenwood Canyon, aptly called one of the crown jewels of the Interstate Highway System. At the heart of the canyon is the Colorado River, flowing swiftly westward over rapids frequented by whitewater rafters. I-70 was built then to the north of the river, with a walking/cycling trail between the eastbound lanes of the highway and the river’s roaring current. At certain points when the canyon reaches its narrowest, the westbound lanes rise above the eastbound lanes along the canyon wall, proving just how difficult it was to extend the interstate this far into the Rockies.

After the Glenwood Canyon, the road rises up to crest the Vail Pass at 10,666 ft (3251 m). While I haven’t gotten terrible altitude sickness for a long time, driving up this pass was one moment when I did seriously consider it on the trip. We stopped at a rest area at the top, alongside countless other travelers, most of whom wanted to take in the sights at such a high altitude, let alone of the remaining snowpack on the tops of the nearby fourteeners. While standing around there in the Sun looking at a paper map of the state given to me at the Colorado Welcome Center in Burlington a week before, I tried to find some scenic routes we could take east in to Denver that would be just long enough to give us something neat to see and do besides just drive on I-70, but not too long as to wear us out before the 8 hour drive the following day across Kansas.

Eventually, we decided to leave I-70 at Frisco, and head south on CO-9 through Breckinridge before continuing over the Hoosier Pass into Park County. From there, we drove to US-285, turning east towards Denver in the high altitude yet wide open South Park Valley around Fairplay. We stayed on US-285 until the small crossroads of Grant, where we turned north on a small narrow road that led us along a series of creeks and streams up to the Guanella Pass (11,669 ft / 3557 m) over the crest of a range just to the west of Mount Evans and down another series of switchbacks towards the old silver mining settlement of Georgetown, which lies along I-70’s path.

The drive from Grant to Georgetown proved to be well worth the 2 hour detour. The views were breathtaking to the nth degree, the road, which was well traveled by many others who like us were getting away from the business of the interstate and the cities, seemed to be an attraction in itself. Along the way we saw the majority of the wildlife we’d seen on the trip, a number of herds of bighorn sheep who spent their days grazing the high mountain grasses along the road. Our descent into Georgetown was marked by the long line of cars and the equally pungent smell of their brakes as our vehicles descended from the pass into that town.

From Georgetown we made our way back into Denver, through the metropolis and out to our last overnight stop at a hotel near Denver Airport. I figured it’d be better on our final day’s drive if we started on the east side of Denver, to avoid most of that city’s traffic, thus speeding up the journey even further. That evening we joined some friends for dinner near the hotel, before a quick night’s sleep.

The following morning, as we awoke to prepare to make the 600 mile drive east to Kansas City, I kept thinking about how different the landscapes we’d been in were from one another. On Friday we’d driven across different shades of desert, on Saturday through the high Rockies, and now on Sunday we’d be crossing the Great Plains, an entirely different shade of golden brown compared to what we saw in the high deserts of Utah and Colorado. As we sped east on I-70, I kept my eyes on the side-mirror next to my seat, looking out first as the hazy mountains receded over the horizon and later as the high clouds that surrounded their tallest peaks slowly began to recede as we moved eastward around the curve of the Earth. To my amazement, I only lost sight of those clouds rising high over the Rockies once we were 40 miles into Kansas just past the town of Brewster.

Conclusion

This has been a wonderful trip, something I’d hoped to do for a long time. As an adult, I’ve been able to experience many of the things I saw as a child over again, visiting cities like Denver and driving through the Rockies, that I’d done so often on summer vacations. Yet now as an adult, I’m able to appreciate these sights far better than before, and to marvel at how wonderful it is that I’ve been able to visit them. While there were still things I wanted to do that we didn’t get to do on this trip, and while I’m left wondering what more I could see and do in the Mountain West, all of this leaves me with a sense of excitement at what the future could hold.

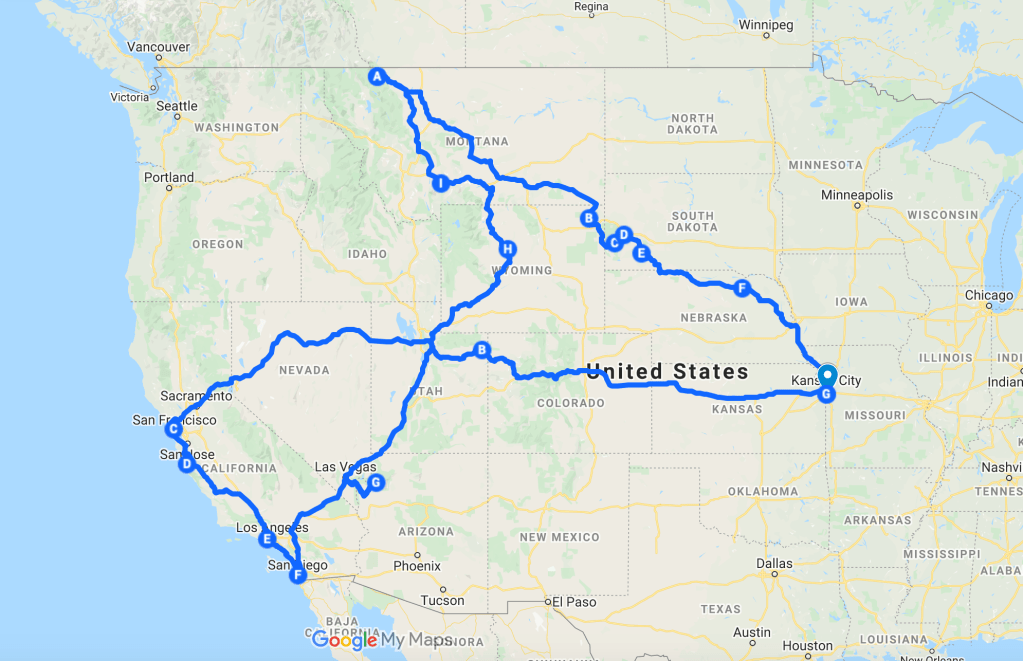

My greatest hope is that that future will prove to be just as pleasant an experience as this week on the road was. In total, we drove 2,652 miles (4268 km) over 8 days. At its western end, this trip took us within a day’s drive of all of the major American cities on the Pacific coast, while throughout we never really strayed too far from either of the major cities we visited, Denver and Salt Lake. It’s amazing to me that we could really be so close to both and yet in so remote of places throughout the week. As Midwestern as Kansas City is, its relative isolation to its neighboring cities, the closest Omaha and St. Louis are 3 and 4 hours away by car respectively, provide this city with a closer experience to its western counterparts than to those in the East, certainly in the Northeast.