On Names – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

Season 4 Finale: This week, to celebrate Christmas I’ve decided to write a bit about naming conventions that I’ve come across, and to explain why I use my full name professionally.

In American culture middle names have a bad reputation. They’re most famously used in our childhoods to scold us, and in adulthood they most often appear in legal matters. A writer naming non-descript American characters John Booth or Lee Oswald might get away with it but include their middle names Wilkes and Harvey and you have two of the most notorious assassins in American history. Most accused or convicted murderers in our legal system tend to be known in the press by their full names: first, middle, and last. There’s an odd cadence to it when these people are identified by the police or the courts. It’s one of the more common times when middle names get used.

I go by my full name professionally. On my website, in my email signature, and in every conference program and academic publication that I’ll ever appear in I’m identified as Seán Thomas Kane. Trust me, I didn’t intend to draw any connection between myself & the men mentioned in the last paragraph who killed two Presidents who I’ve always looked up to. In my case, the use of my middle name has a different sort of significance. In my extended family I often get called Seán T., in part because I have many relatives who are named Thomas, one of whom goes by T. among the family. Whether intentional or not, my parents gave me one of the most traditional Irish names they could have. Irish names are traditionally patronymic, meaning the person is so-and-so, son or daughter of so-and-so, descendant, son, or daughter of so-and-so. Those last names (or surnames if you aren’t American) that begin with O’ refer to families who are descended from a specific person who lived centuries ago. The ones that begin with Mc however are Anglicizations of the Irish word mac, meaning “son” of a specific person who lived centuries ago. My father’s name is Thomas, so in Irish my name is Seán mac Tomás, or Seán, son of Thomas. Kane is an Anglicization, or better an English phonetic rendering of the Irish name Ó Catháin, pronounced two different ways depending on where you’re from in Ireland (for those reading this, listen to the podcast to hear those two pronunciations.) Cathán was a more common Irish given name in the Early Middle Ages and derives from the word cath meaning battle.

This was in the back of my mind when I decided to start going by my full name professionally. It was 9 March 2016 and I had a few hours without much to do while waiting for a car to pick me up at Lyon-Saint-Exupéry Airport on my way to the eastern French city of Besançon, the capital of the Franche-Comté region and a city which Caesar mentioned in his book about the Gallic Wars (De Bello Gallico 1.38). That cold and rainy Wednesday in March there was a national railway strike in France and I ended up booking a back seat of a Renault Clio driven by a Frenchwoman who spoke little English alongside two other Frenchwomen who again spoke little English from Saint-Exupéry Airport outside of Lyon to Besançon, a good 4 hour drive. Right before they arrived though, I was on Facebook posting an update about my trip and thinking about how I wasn’t entirely sold on sticking with Seán Kane as my name professionally, after all when you search Seán Kane on Google you get a fair handful of results. There on Facebook I noticed that my friend Luis Eduardo Martinez, a fellow graduate student in International Relations and Democratic Politics at the University of Westminster, and a gentleman who I consider a good friend to this day, used his middle name professionally. I felt inspired and changed my name on my Facebook profile from Seán Kane to Seán Thomas Kane then and there standing in the airport parking lot.

This proved to be even more advantageous when the Renault carrying the three Frenchwomen arrived as the driver stepped out and proved that the way Seán is spelled makes little sense to a monolingual French speaker. I remembered when I started studying French at Rockhurst University and we chose French names to use in class how I immediately was discontented with being called Jean alone, as I’d rather be called Jean-Thomas because that’s essentially a French translation of my name coming from Irish. So, I suggested that she call me “Seán-Thomas” which was heard as “Jean-Thomas.” Et voilà, that’s how it all got started. For the record: the Irish name Seán is in fact just an Irish spelling of the twelfth century Norman French pronunciation of that French name Jean, which is also the source of the English name John. You can hear the connections better in an English accent than in my own American one where the oh sound in John has shifted closer further forward in the mouth.

This wasn’t the first time I’d changed my name on my Facebook profile. For a while in high school, I went by my Irish name, Seán Ó Catháin, and that was the name on my early membership cards with the Ancient Order of Hibernians. Yet as much as I was inspired by the Gaelic revival and wanted to do my part to restore our ancestral language, I found that it was impractical to use in America and that deep down I do identify more with Kane than Ó Catháin because that’s the name my grandparents, my dad, and most of my paternal relatives use. Kane itself began as a misspelling by the U.S. Army draft sergeant processing my great-grandfather Thomas Keane when his number was drawn in 1918. He enlisted and served as an artilleryman in France and eventually became an American citizen as Thomas Kane because the sergeant told him if he wanted that first e added back into Keane on his papers he would have to go back to the back of the line and start the process over again.

So, to answer a question I often get in Kansas City: no, I’m not related to any other Kanes in this city except my Dad, and in fact outside of my Dad and his brother’s family all of my living paternal relatives who share our family name on either side of the Atlantic spell it Keane. I suppose I could change mine back to that one, I suspect my granddad’s cousin and longtime Wednesday Blog reader Sr. Mary Jo Keane would’ve approved of that, yet at this point the name dispute feels moot especially considering the Keane spelling only goes back another generation or two to about the 1850s before which in the official British government records written in English my great-grandfather’s great-grandfather’s name was written as Thady Caine. In Irish his name would’ve been Tádhg Ó Catháin, and we know he spoke Irish as his first language. So, what was his name? I’m honestly not sure.

I like how different naming conventions reflect different cultures in their own ways. Our Irish patronymic system is really more Gaelic than Irish, after all it’s the same system that’s used by our Scottish Gaelic speaking cousins and it mirrors a very similar system used in Welsh. In fact, my Welsh ancestors’ family name was Thomas, which derives from the Welsh ap Tomos. Fitting, eh?

When I teach about the Vikings I like to bring up the Norse patronymic system too and explain that Leif Erikson (as we call him in English) was actually Leifr Eiríksson in Old Norse, and that following this tradition as it’s today practiced in Iceland were I born there, or should I someday immigrate to that island republic I’d probably start going by an Icelandic version of my name: Jón Tómasson, dropping the Ó Catháin/Kane family name all together in regular use there to better fit Icelandic society while still retaining it outside of Iceland. I see this as similar to how patronymics are used in Russian, where Tolstoy’s tragic character Ivan Ilyich is known by his first and middle name and not by his first and family names Ivan Golovin as we’d do in the English-speaking world. There, for the record, Seán mac Tomás would translate as Иван Томасaвич (Ivan Tomasavich).[1] In a hypothetical blending of cultures where Irish speakers interacted more with French speakers in North America than with English speakers I could see our patronymic system developing into the French system of having double names, thus why when I still published a French translation of my C.V. I would write my name as Seán-Thomas with the hyphen which I don’t use in English.

Another set of naming systems that I’ve encountered that I appreciate are those originating on Iberia where the family names of both the mother and father are included. My same friend Luis Eduardo Martinez’s full name, and the name I first read when I met him in September 2015 is Luis Eduardo Martinez Mederico. In this Spanish naming custom, his father’s family name appears first followed by his mother’s family name. This is opposite to the Portuguese where the maternal family name precedes the paternal one. So, in the Spanish custom my name would be Seán Thomas Kane Duke, while in the Portuguese custom it would be Seán Thomas Duke Kane. My parents and I actually refer to our family as the Duke-Kane Family, and we’ve joked about what my life would’ve been like if I’d been given both family names at birth in that order. I often conclude that including the East Yorkshire name Duke alongside Kane would’ve made me sound more English.

Then there are the professional names like Smith or Miller. These derive from the first bearer’s profession, so Jefferson Smith had an ancestor somewhere in the distant unwritten past of that Frank Capra film’s imagination who was a blacksmith. Today, on Christmas, we celebrate someone who has such a name, that being Jesus. I get annoyed with my fellow Americans who see “Christ” as Jesus’s last name because it’s not a name at all but a title in the first stage of becoming a name. This name as we understand it ought to be written in English as Jesus the Christ, from the Greek Ἰησοῦς Χριστός through the Latin Iesus Christus, but that word Χριστός is merely a Greek translation of the Hebrew word māšiah (מָשִׁיחַ), which again is usually rendered in English as Messiah, the name of Handel’s most famous oratorio and what Brian certainly wasn’t (he was a very naughty boy.) This is a kingly title, fitting with our view in Christianity of Jesus as priest, prophet, and king appears most prominently this time of year in the Feast of Christ the King, something we celebrate in the Catholic Church at the Liturgical New Year, which was 24 November this year.

A brief digression here: this past Feast of Christ the King I learned that the official name of the day is the Solemnity of Our Lord Jesus Christ, King of the Universe. While that last title might sound overly grandiose in the twenty-first century it actually comes from Ancient Mesopotamia, where the most powerful monarchs of those city states as far back as Sargon of Akkad (r. c. 2334–2284 BCE) claimed this as their imperial title: šar kiššatim, which actually meant King of Kish, the primate of all Mesopotamian cities and according to the older Sumerian King List it was the first city to crown its kings following the Great Flood. So, in essence this title places Jesus, a humble carpenter who was incarnate as God the Son as the true “King of Kings (forever, and ever) and Lord of Lords (for ever and ever)” to quote from the Handel.

Now, back to that rendering Christ as Jesus’s last name. In his lifetime, Jesus was known as Jesus of Nazareth, and in earlier times Christians were known as Nazarenes (Acts 24:5). This word is still used to describe Christians in Hebrew in the form notsrí (נוֹצְרִי) and in Arabic with naṣrāniyy (نَصْرَانِيّ). Thus, he was known more by a locator name than by a last name in the modern American sense. Furthermore in John’s Gospel, St. Philip referred to Jesus as “Jesus, son of Joseph, from Nazareth.”[2] So, in the culture in which Jesus was born he would’ve been known most fully in this way rather than with any last name that we may recognize. It’s important to remember that Jesus’s ministry took place 2,000 years ago, and contrary to some popular belief he didn’t speak English. English wasn’t even a language then, though an older form of Irish was around, just probably not heard as much in Galilee or Judaea.

So, let me conclude with the bits that seem to have started as identifiers that came at the end of people’s names before there were family names in the sense that we use them today. These are often locators of where the person in question was from. In the case of Leonardo da Vinci, da Vinci merely refers to the fact that Leonardo was born in the Tuscan commune of Vinci. These particles of place tend to denote nobility in some names, see the French, Spanish, and Portuguese de, the Italian de’ and di, and the German von. However, I see the utility in having this locator in someone’s name to make it clear that even though they’re a Booth they’re not related to every other Booth around. That way a random John Booth living in 1865 would’ve had less trouble because of his more infamous counterpart’s scheming that Good Friday. I’d ask though, in my own case whither would such a locator in my name identify? Where would it refer to? Would it stick just with me, saying that my original hometown is Wheaton, Illinois, so I’d be Seán Thomas Kane of Wheaton? Or would it go back to the origins of my particular Kane/Keane/Caine/Ó Catháin family in the Derryhillagh townland outside of Newport, County Mayo, in Ireland? In Irish the way this would be written would either be with a different Irish preposition ó (yep, there are at least two of these), or with the preposition as. In my Irish as I speak it, I say as in this context more than ó, as in to say “Is as Meiriceá mé,” or “I am from America.”

We don’t do these in Irish names, in part because of our patronymic system which does a fine job on its own. Sometimes when I’m writing stuff in Latin and I want to adopt the style of the Renaissance humanists who I read in my research I’ll try to Latinize my name with one of these locators, rendering my hometown of Wheaton, Illinois by using the name of the Roman goddess of what, Ceres, and essentially making a town name from there. Thus, Wheaton becomes Ceresia. The tricky thing is that when I’m translating my name into Latin, something that was done in academia more into the nineteenth century but is almost never done today, I have a conundrum of whether to start from Kane or from Ó Catháin. I for one don’t like how a Latinized Kaniussounds, so instead I do go from Ó Catháin and use Cahanius, or Ioannes Thomae Cahanius Ceresius in full.

Names are important, and they say as much about the person who bears them as the people who named that person and the culture to which they belong. I’ve played around with my own name a fair bit, as you’ve seen. Today I’m more used to being called Seán-Thomas in French than in English, though the latter has happened more and more. I’ve even noticed that people have started calling me Thomas seeing that name and recognizing it faster than they do Seán, especially with the fada on the a. I smile and acknowledge them, after all I’m happy to be mistaken for my Dad. Looking forward, should I be fortunate enough to name my own children I’ll say these two things: first I’m not the one who’ll be pregnant with them for nine months, so I shouldn’t get first call on their names, and second there’s that Irish tradition that offers a simple answer to this conundrum. Will my first-born son be named Thomas as well then? Yeah, maybe. We’ll have to wait and see how this poorly named lifetime membership with one of the dating apps works out for me. I certainly hope I’m not putting my name out there for the rest of my life, though you can bet I’ll be using that lifetime membership joke for as long as I can.

Nollaig shona daoibh a léithoirí rúin! | Merry Christmas, dear readers!

[1] NB: I’m using Russian as the example here because that’s the one I’m more familiar with. No political inclinations toward the Kremlin in their invasion of Ukraine are intended.

[2] John 1:45 (New American Bible), see more here.

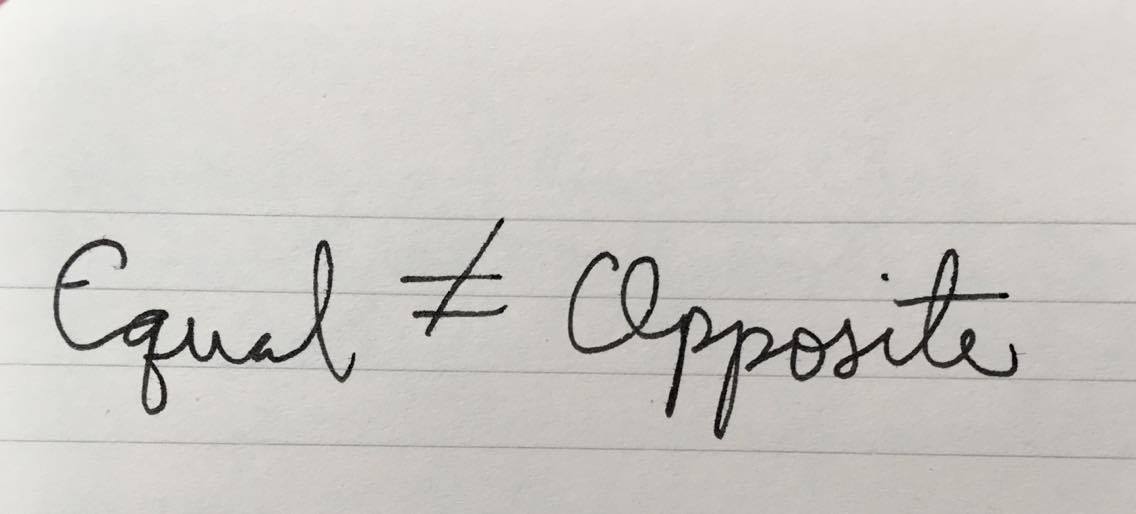

One of the fundamental maxims of physics is that “For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction.” For everything that is said or done something of equal vigour must be in order. By this logic then, for every fascist, far-right, or white supremacist threat to American society and we the American people there must also be an equal reaction by the far-left, by the Anti-Fascists as they have deemed themselves. Yet what good does the threat of violent action do? What is the point of bringing one’s guns to an anti-fascist protest? What is the point of eradicating the memory of all who have had some dirt upon their hands, who committed evils in their lives?

One of the fundamental maxims of physics is that “For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction.” For everything that is said or done something of equal vigour must be in order. By this logic then, for every fascist, far-right, or white supremacist threat to American society and we the American people there must also be an equal reaction by the far-left, by the Anti-Fascists as they have deemed themselves. Yet what good does the threat of violent action do? What is the point of bringing one’s guns to an anti-fascist protest? What is the point of eradicating the memory of all who have had some dirt upon their hands, who committed evils in their lives?

At this point in time, after so many terror attacks around the world in recent years, my initial reaction to the attack in London last night was somewhat muted and reserved. I was not surprised that it had happened; yet I was nevertheless deeply distressed that innocent people would be so brutally assaulted. The three attackers, their identities as of yet unannounced by the Metropolitan Police, will spend eternity lapping in the seas of ignominy, far from the verdant peaceful halls of rest that they may wished to have known.

At this point in time, after so many terror attacks around the world in recent years, my initial reaction to the attack in London last night was somewhat muted and reserved. I was not surprised that it had happened; yet I was nevertheless deeply distressed that innocent people would be so brutally assaulted. The three attackers, their identities as of yet unannounced by the Metropolitan Police, will spend eternity lapping in the seas of ignominy, far from the verdant peaceful halls of rest that they may wished to have known.