The End of an Era – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

This week on the Wednesday Blog, my perspective on the last century and a half as a time of tremendous change.

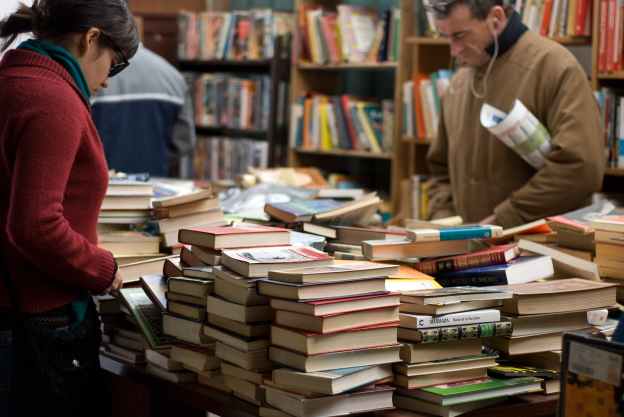

On my first day in London this October I walked from the British Museum, my first stop in the capital, to Charing Cross Road where I made my way into Foyles, my favorite bookstore in that city. Foyles has a wider variety of titles than I’ve seen in most bookstores, and especially titles that catch my attention time and again. I didn’t plan on walking out with a new book, and I stuck to that plan, yet I saw several books which I’ve since acquired in other ways since I got home (I do kind of feel bad about that.) I didn’t pack for this trip with new acquisitions in mind, leaving little room for anything new in my luggage.

Still, I loved wandering through the aisles and shelves of Foyle’s and catching up on the latest that the British publishing industry has to offer, five years after my last visit to that island. Here in the United States, I see some reviews of books printed in Britain, usually in the New York Times or through interviews on NPR, but by and large I’d cut myself loose from the British press that I read, listened to, and watched throughout my adult years. Unlike previous trips back to London, a city that became a home-away-from-home for me in 2015 and 2016, I felt like I’d missed a great deal and had a lot of new things to discover on this trip.

One book that caught my eye several times was Michael Palin’s new book Great-Uncle Harry: A Tale of War and Empire which tells the story of the author’s own great-uncle Harry Palin whose life saw the end of an era and the beginning of our own tumultuous time. Harry Palin was working on a farm on the South Island of New Zealand when Great Britain and its Empire entered the First World War in August 1914 and enlisted with the New Zealand Expeditionary Force, one-half of the famed Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZACs). The elder Palin survived the Gallipoli Campaign and for a while on the Western Front until he died during the Battle of the Somme in 1916.

Two weeks after seeing Great-Uncle Harry on the shelves of Foyles I was reminded of it by something else and bought a copy of the audiobook on Audible to listen to, read by the author, in the car on my way to and from the school where I currently work. The life and story of Harry Palin animated my drives to and from the school where I now work over the last two weeks and left me both inspired to think about the end of the nineteenth century, a period in our recent history that I’ve always been fascinated by, and horrified by what became in the twentieth century.

I chose to not study the end of the nineteenth century and turn of the twentieth century professionally because of the looming specters of the World Wars ever on the horizon of my memory of those moments in history. Harry Palin’s story reminded me of what I love about that period as much as at the end of his life what horrifies me about the experiences of his generation.

The world that existed in 1914 was one which had a continuity with the generations that came before it. There were some major shifts, the revolutions at the end of the 18th century and in 1848 come to mind, yet none of those in Europe were permanent. The needle of change wavered throughout the century leading up to the First World War. All of that changed as old institutions, which had long weathered the storms and basked in the sunshine of Europe’s history now collapsed under the tides of change released by the hands of their own officials. That war is perhaps the greatest example of hubris among any political leaders yet seen in our long history. Men who thought they could expand their empires, enhance their prestige and honor by waging war against each other instead lost their crowns and left millions dead in the wake of the conflict they unleashed.

When I read histories of this period, I often want to shout at the characters to look out, to be wary of what is coming; for in a Dedalian way I worry we can become too complacent and hawkish yet again. Our caution is well learned, now after a century which saw two world wars and countless other conflicts born from those furnaces. In the wake of the first war a great instability allowed for experimentation to occur. This is a natural thing, something I see in the Renaissance and Wars of Religion (the period which I study) yet in the context of the twentieth Century it marks something far darker. This experimentation in politics and economics led to a further world war in which the three new dominant ideologies –– communism, liberal democracy, and fascism –– collided. Out of it, fascism fell but not before taking millions with it, and a cold war simmered which defined the rest of the century.

In my own life, a further reduction in the formalization of conflicts has played itself out. Now instead of great armies facing off in large-scale battles like those known in the world wars, or even the proxy wars fought by the superpowers we see violence wrought through terrorism. The front lines are not so far away when the threat of violence, whether foreign or domestic could be around the corner. Our children practice for the possibility of an active shooter in our schools because such an incident has happened time and again, and I’ve internalized the reality that in my profession I’m likely to experience such an attack as long as I continue to teach.

I go to places like Foyles to get away from these worries and horrors, to discover new ideas and ways of looking at the world that I was previously unaware of. On this trip, it occurred to me several days before my return to London that I was left bereft of worries, a feeling of calm that I hadn’t felt in a very long time. It almost left me feeling a loss for something I’d long known. I chose to work on a time period further removed from the present to have a refuge in my work from the horrors of the recent past that shaped my world; yet this is still my world, our world, and for as many problems as it has there is a lot that I feel nostalgic for about the century now passed. Even as I write now in 2023 and will likely be remembered as a voice of the twenty-first century, I will always think of myself just as connected to the twentieth, in which I was born and during which a great many of my formative memories occurred.

It occurs to me now that as much as we live in a continuation of the new era born out of the First World War, perhaps the general crisis we find ourselves in now, from the wars my country fought throughout my teens and twenties to the climate crisis we now witness, is bringing us into an even newer era. I hope it will be better than the last, and that maybe this time we’ll find a way to live up to the highest ideals of our predecessors.