Bad Practices in Baseball Broadcasting – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

As you’ll have gathered from last week’s episode, I’m a big baseball fan. I always have been, and probably always will be. Baseball was the first sport I watched as a kid, the first I played (Kindergarten T-Ball), and the one that I have spent the most time watching both in the stadium and at home on TV. Growing up in the 90s and 2000s baseball was one of a handful of things that were just normal to have on the TV or the radio during the day in the background. No matter which major league city you were in, the local team or teams would probably be on the airwaves on any given Spring or Summer afternoon or evening.

As a lifelong Cub fan, I was lucky after my parents & I moved to Kansas City in June 1999 to be able to still watch the Cubs live on WGN’s national superstation. Those broadcasts became one real big constant in my young life, something I even introduced to my cousins on occasion during those long summers in the early 2000s when I spent the day at their house. They were all Royals fans first and foremost, but I distinctly remember one particularly exciting game from Wrigley when we all were buzzing with excitement in front of the TV watching an especially close day game, cheering & celebrating when the Cubs won with a walk-off home run in the bottom of the 9th.

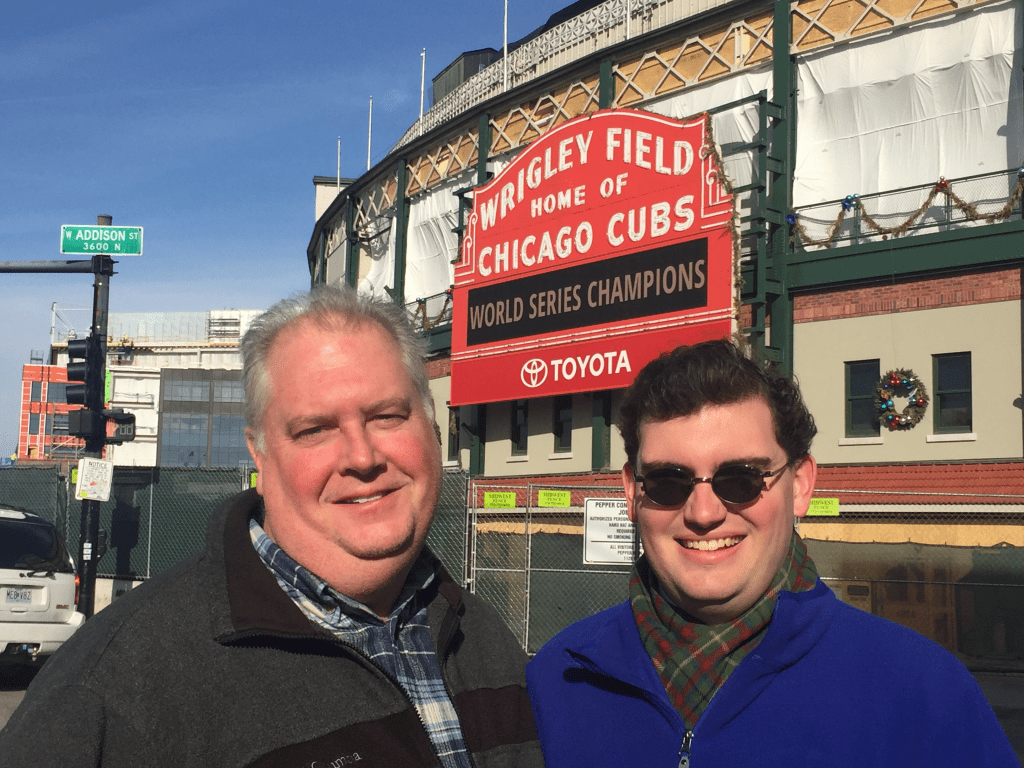

That all began to change in the early 2010s when baseball began to move from the ubiquitous over-the-airwaves channels to special sports channels that you either got through your cable package or that were only available at special request. The Cubs left WGN in 2015, and one of my last day-to-day links with my original hometown went with the last of those broadcasts. I didn’t notice it at first, in September 2015 I moved across the water to London to do a master’s degree in International Relations and Democratic Politics at the University of Westminster, and only rarely got to see baseball at the odd American restaurant in the British capital. When I returned to the U.S. the following year the Cubs were almost always on MLB Network or any of the other regular baseball broadcasters, mostly ESPN and Fox Sports. It was 2016, the year when the drought was finally lifted (see last week’s episode for an emotional recounting of the night of Game 7). In the following years I was able to see the Cubs fairly regularly on national TV, and the Kansas City Royals, my favorite American League team on the local Fox Sports Kansas City broadcasts on a daily basis, but as the 2010s ended all that began to change yet again.

Around the same time as the beginning of the pandemic in this country in March 2020 the news broke that Fox was selling their Fox Sports division as a part of the Disney acquisition of 20th Century Fox. The Federal Trade Commission ruled that Disney couldn’t control Fox Sports and ESPN, that’d be a monopoly, so Fox Sports was up for grabs to the highest bidder. That bidder turned out to be Sinclair, America’s shadiest right-wing owned media conglomerate, the Hearst of the 21st century, the true Charles Foster Kane. I wasn’t happy from the beginning about this; Sinclair had been caught red handed making their local news anchors read a prepared statement that sounded way too much like propaganda for my liking, and nearly anything they touched seemed to be weaponized to benefit their own ideals and mission. So, when Sinclair announced that the Fox Sports naming rights had been sold to Bally’s, the casino chain, I wasn’t totally surprised. One thing to get out of the way: I’m fine with legalized sports betting, I’m just annoyed with how gaudy and grotesque its advertising often tends to be, and frankly I don’t want any part in it. What frustrated me the most was that as a part of the deal Sinclair decided to get greedy, as robber barons are known to do, and raise their rates to the point that Fox Sports, now Bally Sports, was cut from most TV providers’ channel listings, especially from streaming TV providers like YouTube TV and Sling. For the first time in my life, I couldn’t watch baseball, whether the Cubs or the Royals, on local TV.

I recognize that this isn’t a serious societal problem on its own. Having professional baseball off the airwaves for a good portion of the population isn’t going to cause people to starve or to lose their homes or their jobs; it isn’t a matter of public education or human rights. Compared to those problems this is insignificant. Culturally though, in a country that is largely isolated from the global sports market, baseball remains our national past-time. It’s something that developed as our country grew, a sport that came into its own after the Civil War with teams that have existed as long as some communities in this country have. My own Chicago Cubs have an old heritage in professional baseball dating back to around 1870. They joined the National League at its founding in 1876 and have stuck around in the same city ever since. For the first 30 to 40 years professional baseball was seen by spectators in the stands and reported on in the newspapers. In the next few decades with the invention of radio it was broadcast around the country alongside sports like boxing to homes and businesses from Atlantic to Pacific. Following World War II it began to be seen on TV screens, with greats like Jack Brickhouse calling games from the press box at Wrigley Field. Some of my fondest memories of baseball are the most mundane ones, like the times I’d sit in my grandparents’ kitchen watching the Cubs with my grandmother, or the summer evenings in recent years when my parents and I would sit around in our living room in Kansas City watching as the Royals played fun small ball, outwitting heavy-hitting teams with their base running, base stealing, and excellent fielding. Memories like those are what companies like Sinclair are burying deep in the ever-receding past.

A year ago, Sinclair announced they’d have a streaming service ready to go for the 2022 baseball season called Bally Sports+ (because every streaming service is called “so and so +” for some reason). The report said it would cost around $23 a month, or $184 per baseball season, including Spring Training and the playoffs (March-October). This would cater to people like me who don’t have traditional cable packages, owing to their exorbitant prices around $80-120 a month, and would fill the void that Sinclair themselves created to gouge the market during the 2020 and 2021 seasons. Well, Spring Training has begun for 2022 and Bally Sports+ is nowhere in sight. I was lucky enough on Monday afternoon this week to catch a Royals Spring Training game against the Angels but that feels more like a chance encounter than a solid resolution to the problem.One potential solution would be to build off the legal exception that the 1922 Supreme Court Case Federal Baseball Club v. National League made for Major League Baseball to be exempt from the Sherman Antitrust Act, the very act which opened the door for Sinclair to buy Fox Sports over Disney’s objections. In the present case, I’d argue that baseball is an exception to the rule because it’s a deep-rooted part of American culture. As such it ought to be available to watch over-the-air, exempt from any special cable or streaming packages, exempt from being hogged by the greedy arms of broadcasting conglomerates like Sinclair. Unlike the NFL, baseball’s closest competitor, Major League Baseball’s season doesn’t lend itself well to having an all-national broadcast schedule. We’re talking about 24 weeks between April and the end of September with 162 games being played by 30 teams, or 2,430 games in a season. A solely national broadcast system like the NFL’s simply wouldn’t work for the MLB. Instead, local broadcasts should be prioritized, and broadcasting companies should be incentivized to put the viewers first. The alternative, if baseball isn’t easy for people to watch on a regular basis, is for the sport to decline in popularity, something that hurts companies like Sinclair anyway. I only hope that Sinclair’s executives realize it’s to their benefit to let people watch baseball at a fair price.