Artemis – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

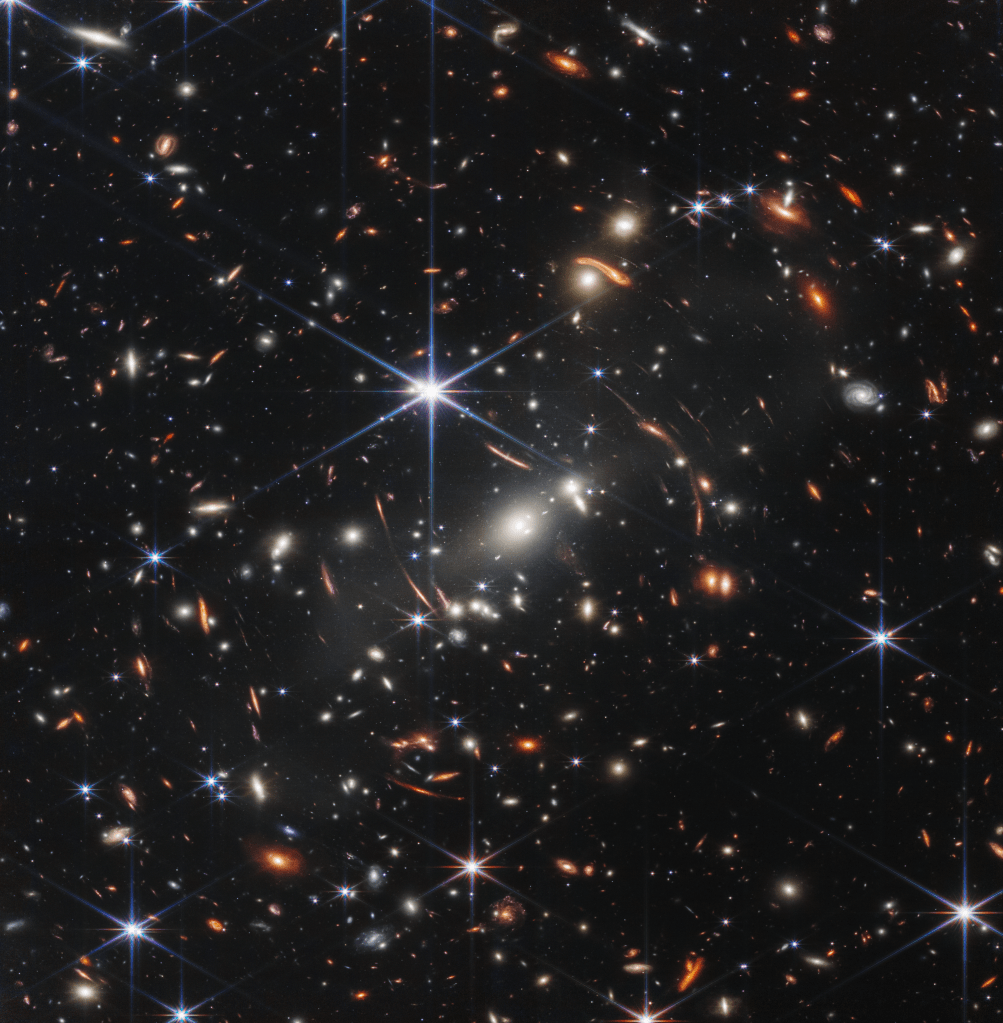

As long as I can remember I’ve known Neil Armstrong’s now immortal words “It’s one small step for Man, one giant leap for Mankind.” They were spoken a couple decades before I was born at a time when my parents were themselves children. I think I may have recognized Armstrong’s voice earlier than many other public figures. Then again, Space exploration has always been a big deal in my life, from the endless sci-fi novels that lined the shelves of our basement library in our suburban Chicago home to the Hubble pictures that adorned the walls of many of my classrooms through the years.

Looking back at a lot of those novels and hopeful calls for future Space exploration and settlement, like Gerard K. O’Neill’s The High Frontier or Stanley Kubrick’s classic film 2001: A Space Odyssey it’s striking how far we are now today in 2022 from where we hoped we’d be over the last 60 years. Our last lunar mission ended 20 years to the day before my own birth in December 1972, and besides the odd Chinese robotic mission we humans haven’t been back to our largest satellite since.

So, in December 2017 when NASA announced the beginning of the Artemis program I was thrilled. Artemis, like its twin Apollo, will take humans back to the Moon at some point later this decade or in the early 2030s. Not only that, but Artemis is supposed to be the beginning of the first permanent human outpost on the lunar surface, the beginning of a new stage of human settlement. Since that announcement I’ve enjoyed the thought that in future when I look up at the Moon, I’ll be able to see from a very great distance places where other humans will be living.

The troubles of the last few years, the great crises we’ve been living in with the pandemic and all its associated problems, have certainly contributed to delays in the launch of Artemis 1, an uncrewed mission that will orbit the Moon and lay the groundwork for future crewed missions in the Artemis program. There were even moments when I admit I worried that Artemis 1 would never leave the ground, like the Constellation program that Artemis replaced.

Many of those worries were relieved a few weeks ago when Artemis 1 was moved onto its launchpad at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida. The rocket, the first launch of the Space Launch System (SLS), a 365 ft (111.25 m) tall super-heavy lift expendable launch vehicle, now waits for its date on the same Pad 39B where the Apollo missions left Earth five decades ago. Only in the last few weeks has NASA given a deadline for this momentous launch: at some point between 29 August and 6 September 2022.

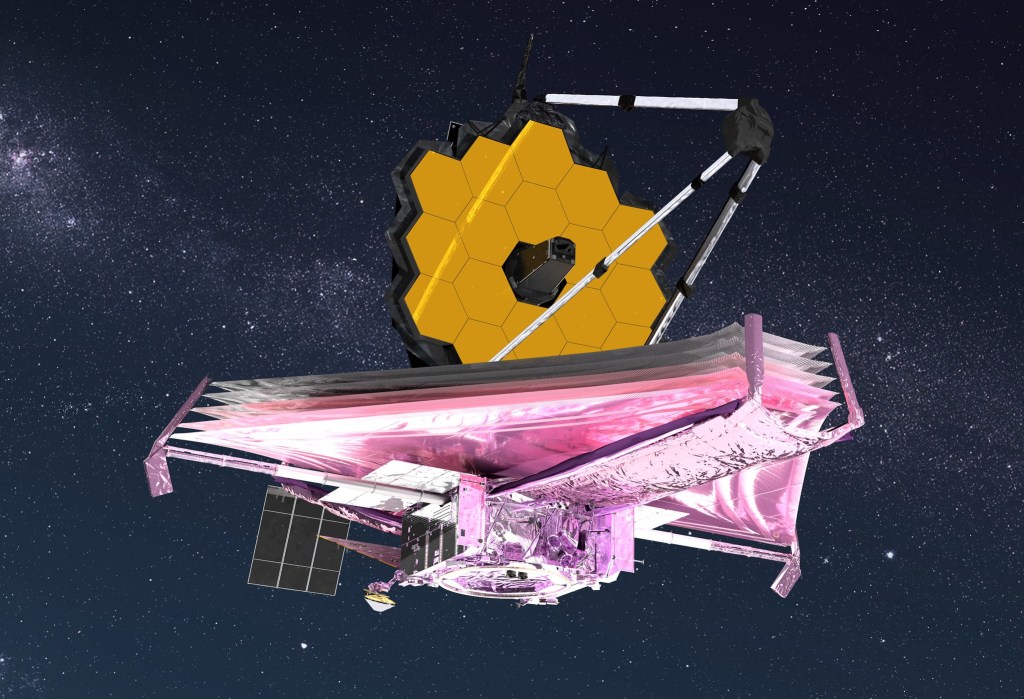

We stand at a point on the verge of entering a new generation in our exploration of Space, a generation when our horizons are far greater than ever before. The dreams of the 1960s haven’t been forgotten entirely, in many ways the Artemis missions to the Moon and the future Martian landings evoke those dreams best expressed in our stories. What’s more, we have a real opportunity here to make a difference through these missions, to let them inspire us to make our lives better here on Earth. I’ve often heard it said from astronauts that seeing Earth from orbit is a humbling experience, because it demonstrates just how interconnected we all are.

It really brings home what Carl Sagan wrote in his book Pale Blue Dot that we are capable of doing so much more if we recognize our common stewardship of this our home, the only home we’ve ever known. We certainly can use Space exploration in the long term to try to find another home, if we continue to mistreat this one so badly that we need to look for a new one, but it would be far better of us if we use these experiences of visiting strange new worlds to use those experiences to appreciate what we have here even more deeply.

My hope is that Artemis will be a beacon of light in an ever-turbulent period in our history, and that it will be remembered as a moment when humanity came together to achieve a common goal for the benefit of all of us.