A Defense of Humanism in a Time of War – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

This week, why we should not lose sight of our common humanity in a time of war.

The news of the last weekend felt like another shot at the optimism that I knew in my early childhood. I was born at a time of triumph for this country in the aftermath of the fall of communism in Eastern Europe when the hopes and dreams of the postwar world seemed like they might finally be realized. I remember the 1990s through a child’s eyes, and so much of the trouble that befell this country and all others in that decade largely fell out of my vision. I remember when the Good Friday Agreement was signed and the Troubles ended in the North of Ireland; it was of particular interest to us Irish Americans whose history was born in the same struggle over generations of immigration. Yet my experiences in those first years planted deep within my soul a desire for people to get along and for the peace we knew in those years.

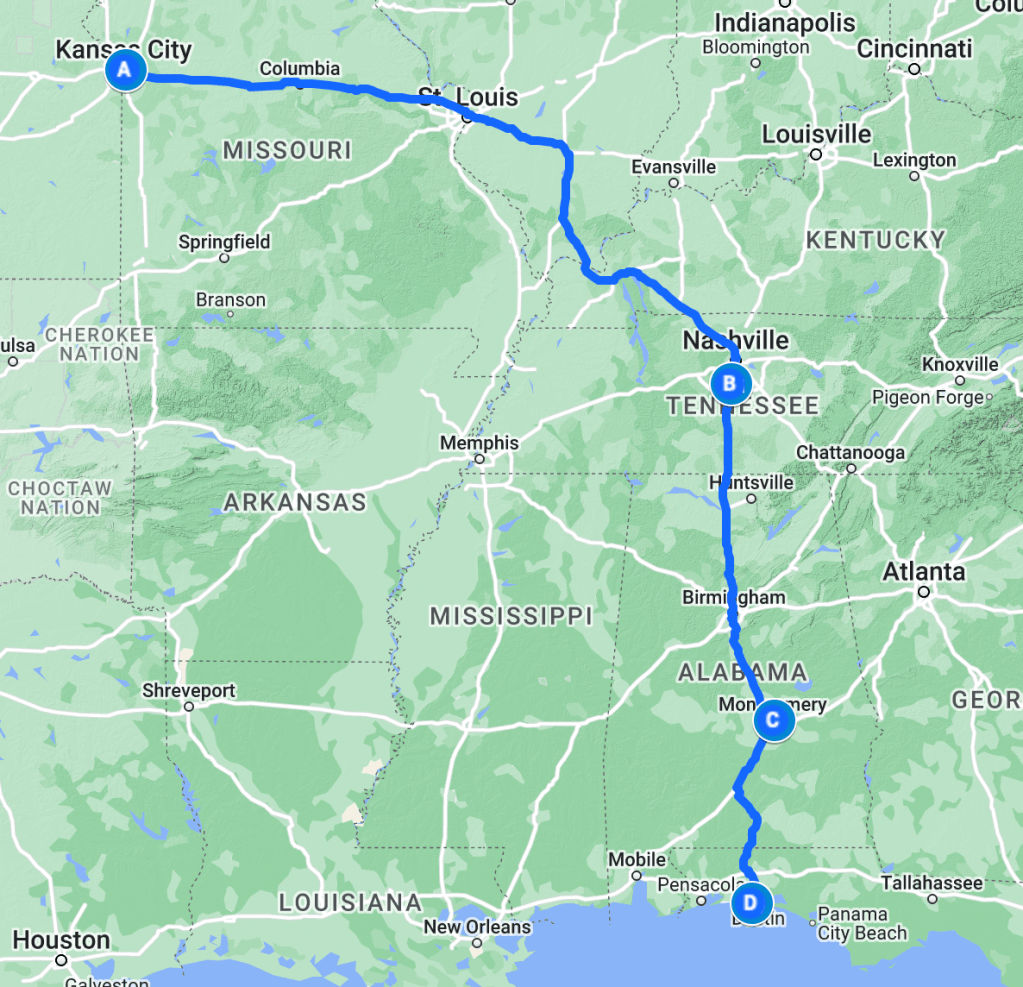

That peace of course faded on that sunny Tuesday morning of September 11th, 2001, when an attack on New York and Washington propelled us into war in faraway Afghanistan. I wrote several years ago in the Wednesday Blog that to me 9/11 marked the true beginning of the twenty-first century, not the millennium celebrations a year before.[1] It was the moment when the hopeful optimism we’d built up suddenly came crashing down and left us scarred and stirring for a fight. Yet Saturday’s news didn’t remind me as much of 9/11. It didn’t remind me of the national unity we saw after the attacks, or the outpouring of sympathy that led to emotional scenes of the Star Spangled Banner and the Battle Hymn of the Republic being played at a royally attended memorial service at St. Paul’s Cathedral. Instead, the aerial attack that the President ordered on Iran’s nuclear facilities reminded me more of a rainy Wednesday in mid-March 2003. That week my Mom and I were in St. Louis visiting my aunt, uncle, and cousins who lived there at the time, and on the morning of March 19th we read in the papers that the rumored war with Iraq would likely start in the next 24 hours. Sure enough, after a day spent at the Gateway Arch, we watched around 9 pm that evening as the younger President Bush made a speech from the Oval Office announcing the invasion of Iraq to topple Saddam Hussein’s regime. All I’d ever heard of Hussein was that he was a bad man, a dictator of the worst sort, and in all fairness he was. Still, none of us watching together in that West County living room expected the war would last for as long as it did.

Combined, the Wars on Terror became a common feature in the childhood of my generation. We knew a time before war, but all we’d seen for so long were these wars fought in distant places that we’d easily forgotten what a time of peace could be like. In general, as a child I thought more favorably of the war in Afghanistan than the one in Iraq, after all our military invaded Afghanistan to overthrow the Taliban regime and capture the perpetrators of the 9/11 attacks. I got used to regularly seeing the convoys of Chinook helicopters flying over our house en route to Fort Leavenworth, 16 miles (26 km) to the north. At certain points during the wars, they flew overhead several times per day. War consumed the American psyche in a way that after a while I became quite uncomfortable with. I began to see the human toll of the wars in the returning veterans who, once the homecoming celebrations were over, were left to deal with their experiences often on their own. I saw a mean-streak that was always there in our society become more prominent directed toward anyone who could be an easy target. I’m sad to say I’ve joined in this from time to time, something I regret.

For as long as any of us can remember we’ve used our religions to justify that mean streak and the violence it produces. Famously, the Mahatma Gandhi is supposed to have remarked that he liked Christianity but had never seen it practiced because Christ preached that we ought to “love our neighbor as ourselves.”[2] How’s that going?

We often think of high-minded ideals like this in a very Augustinian context, that it’s something we’ll get to when we need to, “Lord, give me chastity and continence, but not yet!”[3] We either haven’t faced our mortality or don’t recognize the humanity inherent to being mortal. Knowing that our lives have an ending gives us reason to act while we can, and in that action, we have the potential to lead our lives and those around us away from the trials of the last quarter-century toward a better life.

When I’m asked to define myself in short keywords, I usually say something along the lines of “I’m a historian of Chicago Irish American Catholic roots.” There are so many different stems that could be followed from the roots of that one statement whence grow the orchard of my life. After all, I’ve lived in Kansas City now since the millennium, in spite of my stubborn devotion to my native metropolis. Yet more and more as I progress further in my career and my studies, reading so often the works of Renaissance cosmographers and naturalists who rooted their lives and work in the revival of the classical Greek & Roman past I’ve come to know more about Renaissance humanism. This philosophical tradition sought to center humanity in our understanding of the Cosmos in contrast to the older scholastic preference for understanding all things in a theocentric manner. Still, some humanists again drew their work as a meditation on Nature as drawn from the Divine Spark of creation. Most prominent among these was Erasmus of Rotterdam (c. 1466–1536) and his friend St. Thomas More (1478–1535) who are two of the most prominent Christian humanists of the Renaissance. I studied Erasmus and More in great detail in my History master’s and wrote about their influence on the education of More’s daughter Margaret Roper (1505–1544) and granddaughter Mary Basset (c. 1523–1572) in my master’s thesis. And as my work continues to progress, I see this same tradition of Christian humanism present in the cosmography of André Thevet (1516–1590) who revolved his accounts of what Joan-Pau Rubiés has called the “Renaissance of global encounters” around drawing a greater understanding of God and Creation.[4]

For years then, living with these humanists in my reading and my work, I found many parallels and descendants of their thought present in the things I was reading for fun. Carl Sagan’s secular humanism for instance owes much of its ancestry to the Renaissance and Enlightenment humanists who came before him. Sagan’s perspective of the minuteness of humanity decentered us from even the Renaissance humanists’ mission yet drew some of these same themes of putting humanity in our rightful, little place from Michel de Montaigne’s (1533–1592) own early skepticism. Like our own time, Montaigne lived and worked in a time of war, Philippe Desan writes that “there were eight civil wars in France during Montaigne’s lifetime.”[5] He laid a skeptical path upon which Sagan would eventually devise his own Cosmos and Pale Blue Dot, a path paved in the decades after Montaigne’s death by Descartes (1596–1650) and in the Enlightenment by Rousseau (1712–1778) and Voltaire (1694–1778). I find so much to be admired in this contemporary secular humanism, I myself agree with the view that religion and politics should be kept separate having seen enough instances of detrimental influence from religious authorities in the political theatre. Perhaps then a better way to define my thinking is as a twenty-first century Christian humanist, following in the path laid by Erasmus and More five centuries ago and building out my worldview with bricks and mortar created from the Catholic notion of social justice and the commonweal which tries to live up to that ideal that we should “love our neighbor as ourselves.”

I know many brave people who have put their lives on the line for others whether in war, in our local emergency services, or in any other capacity. The Catholic Church teaches a theory of just war, which I’ve long had trouble with. At the start of the current war in Gaza I wrote about this, deferring the question to say

“I’d rather negotiate for as long as possible, try to find common ground with a potential enemy in the same way that I try to speak to those I interact with on a daily basis in their own language. Yet sometimes it does come down to this question of whether after all the negotiating and the impasses that have resulted if fighting is justified?”[6]

In that blog post I tried to connect the war that never needed to start in Gaza to Montaigne’s own criticism of his fellow Frenchmen during their Wars of Religion. As this war has progressed, I’ve concluded that the only justifiable side to take is to reinforce my own claim to humanism and hope and pray and in my own way quietly advocate for peace to my elected officials. Just as I’ve known many brave people who were willing to die for their beliefs in the uniformed line of duty, I’ve known many also who are willing to face arrest, condemnation, and even death to stand up to the horrors we unleashed upon ourselves 80 years ago when we entered the age of nuclear war. I’ve known priests and nuns through the years who have stood up to the evil ways in which our scientific advances have been used for the sake of all of us. The President who ordered the atomic bombs be dropped, Harry Truman, is a local to Kansas City, and knew several of my relatives. My great-grandfather Gene Donnelly always said that the bombs saved his life and the lives of millions of others as preparations were well underway for the Allied invasion of Japan 80 years ago this summer. Again, with the question of just war, when this moral question of whether Truman should’ve used the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki comes up, I don’t have an easy answer because I can see both sides of the question.

So, this Saturday when the news broke that the current President ordered an aerial attack on three of Iran’s nuclear facilities, I wasn’t surprised, but I was certainly scared. For my entire life, and for much of my parents’ lives we’ve lived in the shadow of war with Iran, a country whose revolution was as much a reaction to American involvement in its own domestic affairs as it was in reaction to the Shah and his government. Over the weekend, as I’ve read more of the reactions to the American entry into the war between Iran and Israel, one shared by a friend in the Kansas House of Representatives struck me the most. The Facebook post was written by a man whose father had taught foreign policy classes about Iran for decades, and several of that professor’s students were involved in the Iran nuclear negotiations initiated and concluded by the Obama Administration a decade ago. The professor’s son made two stark points: this was the first time we had approached the Ayatollah’s government as respectable partners, and in part because of this we reached a peaceful settlement with Iran on the question of their nuclear program, but that peace was eliminated by the current President after he was first elected in 2017. Why? Another friend of mine made the point that until peace is more profitable than war, we will know only war. I remember what peace was like, though living in this armed camp of a country I doubt I’ll see it anytime soon. The reactions here at home to our attack on Iran fell along the same partisan lines as every other issue these days. The President’s supporters cheered him on, while those of us opposing his agenda questioned the constitutionality of the attack considering Congress was given no prior notice.

What strikes me most is that this President says he seeks peace. On Monday afternoon he announced on his social media platform that he’d negotiated a ceasefire between Iran and Israel that would go into effect at 6 pm Eastern Time. Yet the following morning I woke to read about more missile strikes in the New York Times. Did he actually negotiate a ceasefire, or was this another social media musing? Does he really want peace enough that he is willing to put his political future and the unity of his coalition on the line? Are any of our political leaders, for that matter, willing to try? I want to make my own effort if not for myself than that the generation now being born might experience that same peace I remember from my youth.

I don’t want to be known as a pacifist; our long history has taught us that there will always be schoolyard bullies to stand up to. Rather, let me be known as a humanist who seeks to raise the human spirit above the petty squabbles of war and violence that have so marked our memory. For if history, philosophy, and theology have taught us anything it is that alongside every call to arms is a cry to try living a better life. While history and philosophy study the rational and discernible aspects of this, it is in theology that we must find stock for our future wellbeing, for we must believe in ourselves and the fundamental goodness of our nature if we are ever to achieve the dream of humanity. For in our beliefs structured in religion’s purest form we reflect the best vision of ourselves.

[1] “Masks,” Wednesday Blog 4.15.

[3] St. Augustine, Confessions 8.7.

[4] Joan-Pau Rubiés, “The Renaissance of Encounters and the Renaissance of Antiquities,” Renaissance Quarterly 78, no. 1 (2025): 1–41, at 12.

[5] Philippe Desan, Montaigne: A Life, trans. Steven Rendall and Lisa Neal, (Princeton University Press, 2017), xxxiii.

[6] “On the Cannibals,” Wednesday Blog 4.20.

Correction: 25 June 2025, 13:12 CDT. Amended a typographical error that latched the final paragraph to the penultimate one.