Paradiso – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

This week’s edition of the Wednesday Blog is dedicated to Micah Holmes.

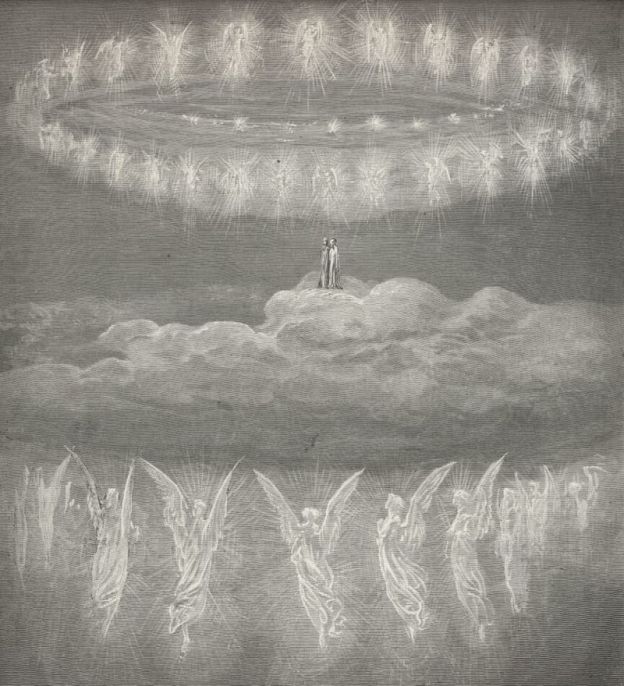

This week, I conclude my three-part reflection on Dante’s Divine Comedy with the Paradiso.

I’ve long wondered about the nature of the heavens, both scientifically through my passion for astronomy, and theologically drawing from my Catholic education and faith. In the Spring of 2011, I staged a one-act play of my own writing called The Swansong of the King which I wrote in the spirit of the scene in John Boorman’s 1981 film Excalibur where Merlin’s ghost appears to Arthur in a circle of standing stones to reassure him before his great final battle at which he would surely die. I wrote Merlin lines that told the story I’d imagined of the soul’s voyage to Paradise, an island amid a deep blue sea where in a valley in the middle surrounded by lush forests, there stands a city of white stone houses and public edifices. Each house is a garden in its own right, looking like an ancient Roman atrium more than anything else, and when the soul arrives, they find the people they always loved waiting for them there for one last great party.

My vision of Heaven draws from other sources than Dante’s; his is the child of a medieval Italian world with deep and still living Roman roots, while mine has in equal amounts classical and Celtic antecedents, the island in essence being the Irish Tír na nÓg, the Land of Eternal Youth. There’s also a bit of Tolkien in there, with the speech that Gandalf gives to Pippin during the Battle of Minis Tirith in The Return of the King that was so wonderfully acted out by Sir Ian McKellen in the film adaptation. Yet upon reading Dante’s cantica of his travels from the summit of Mount Purgatory to the ultimate light at the apex of all Creation, I can understand where he was coming from even if I found my understanding of his verse fading in and out at times.

Early in the Paradiso, Dante writes in Canto 5 about acknowledging one’s mistakes, in Beatrice’s words “Better for him if he had said: ‘I’m wrong,’ / than to do worse doing it.”[1] So, the vision I’ve held onto since childhood of Paradise may well be lacking, while it makes sense in my understanding I could still very well be wrong in my assessments, and in that I would be joyous to be proven wrong so for that would mean that this affirms one of the greatest truths that I believe in: that there is always more out there for us to learn.

All things that we know exist within creation, Beatrice describes in Canto 7 how all things “come to decay and last no time at all,” on Earth, yet in them something greater can be seen. In Paradise, Dante meets many saints and holy men and women. There too, he lives out the genealogist’s dream by speaking to one of his ancestors, Cacciaguida (c. 1098 – c. 1148), a knight who left Florence to join the Second Crusade during which he was knighted by Emperor Conrad III (r. 1138–1152). When asked who he was, the knight responds to Dante, “My branch and leaf (in whom I was well pleased, / waiting until you came) I was your root.”[2] Yet when Dante asks the question I’ve long wished I could ask my own ancestors from whom I inherited my family name, “Tell me my earliest, my dearest growth / who were your own progenitors? Also, / what years were marked for you as boy and youth?”[3] Cacciaguida replies that his ancestors lived in Florence as did he and Dante, concluding “that’s all you need to hear of my great sires.”[4] Among my own Kane ancestors––the name is variably spelled Keane, Kane and Caine in English but consistently as Ó Catháin in our native Irish––the unbroken recorded link only reaches as far back as my great-grandfather’s great-grandfather who is identified in Griffith’s Land Evaluation in the 1840s as Thady Caine. I’ve surmised that he was likely born at the earliest in the 1790s. The memories of these people who in worldly affairs had little impact yet still existed as a part of our history deserve to be remembered as we still exist as a part of their legacy.

As Beatrice leads Dante higher and higher through the celestial spheres, he notices how her laughter and joy evokes the spirit of their surroundings. In Canto 18, Dante writes that upon turning to Beatrice he:

“saw the light within her eye so clear,

so full of laughter that her look and air

defeated all that these, before, had been.”[5]

One passage, in Canto 19 that struck me as needing particular note concerned the salvation of those who are born outside of Christendom and live good and worthy lives. In Dante’s verse:

“’A man is born,’ you’ve said repeatedly,

‘beside the Indus. And there’s no one there

Who speaks of Christ, or reads or write of Him.

And all he does and all he means to do ––

As far as human minds can tell –– is good,

sinless alike in living and in word.

Then, unbaptized, beyond the faith, he dies.

Where is the justice that condemns him thus?

Where is his guilt, if he does not believe?”[6]

Here, I feel that Dante is asking about the salvation of his first guide through these three realms, Virgil, who is condemned to eternity in the First Circle of Hell for the fact that he was born and died just too early to have encountered Christianity. It’s a question that I certainly have, having known many people who do not practice this faith yet have lived good and true lives. I don’t have an answer here, like many questions of faith this is something that remains a mystery to me, for I can see both sides of this question. What I can do is hope in love, which Dante writes is the purest and truest emotion evoked from God’s Essence:

“Love, which in laughter sweetly clothes itself,

how ardent in those piercing pipes you burned,

voiced by the breath of holy thoughts alone.”[7]

In that essence of love, Dante sees Beatrice slowly immerse herself into the orbit of God, beginning in Canto 21 and continuing through to the end of the Paradiso in Canto 33. In the first of these two canti, Beatrice warns Dante that he is not ready to see her in her full beauty enhanced by the presence of God:

“’If I were to smile,’

so she began, ‘you would become what once

Semele was, when she was turned to ash.

For if my beauty (which, as you have seen,

burns yet more brightly as it climbs the stair

that carries us through this eternal hall)

were not now tempered, it would shine so clear

that all within your mortal power would be

a sprig, as this flash struck, shaken by thunder.”[8]

Here Dante drew from the classical inheritance, evoking the story of Semele, daughter of Cadmus of Thebes, the founder of Tyre, who was one of Jupiter’s lovers and was tricked by the jealous Juno to ask to see Jupiter in his full majesty only to be reduced to ash by seeing him.[9] I’m reminded as well of the Irish legend of the return of Oisín to Ireland after spending 200 years in Tír na nÓg with his wife Niamh only to turn to ash when he fell onto mortal soil again, but not before having a long discussion of faith with a certain Christian missionary named Patrick. In both Dante’s use of the myth of Semele and this clear Christianization of the death of Oisín, the one ancient hero who by all druidic accounts still lived in the Irish Paradiso of Tír na nÓg, the new faith could incorporate the old worlds into which its light flooded over the last two millennia.

At long last though, Dante is able to see the “sacred light” in its purest form, and to look again at the face of Beatrice illuminated by this light as one of the righteous. Later again in Canto 21, he proclaims with the exuberance of the Magnificat:

“O sacred light,

how love – the freedom of this holy court –

is all one needs to trace God’s providence.”[10]

Dante can see the truth of Paradise because of the caritas, the charity, “on high that makes us serve / so readily the wisdom of the spheres.”[11] This light overwhelms Dante, even then. This is something that I fully can relate to, having felt much the same throughout my life yet magnified in recent months. In the first lines of Canto 22, the poet writes:

“Astounded, overwhelmed, I turned to her

my constant guide, like any little boy

who’ll run to where his greatest trust is found.

And rushing there, as mothers always do,

her shocked, pale, sobbing son, she said to me:

‘Do you not know that you’re in Heaven now?

Or know the heavens are holy everywhere,

and all here is done is done from zeal?”[12]

Even in this moment when Dante ought not to be afraid, he still felt that most human of instinct at beholding something otherworldly and so beyond what he had seen before then. The immensity of Paradise alone would make anyone of us cower in fear. These verses more than any other spoke to me directly, as something that I could see myself doing in Dante’s place. It reminds me of Moses’s first reaction to realizing whose voice spoke to him from the burning bush:

“I am the God of your father, he continued, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob. Moses hid his face, for he was afraid to look at God.”[13]

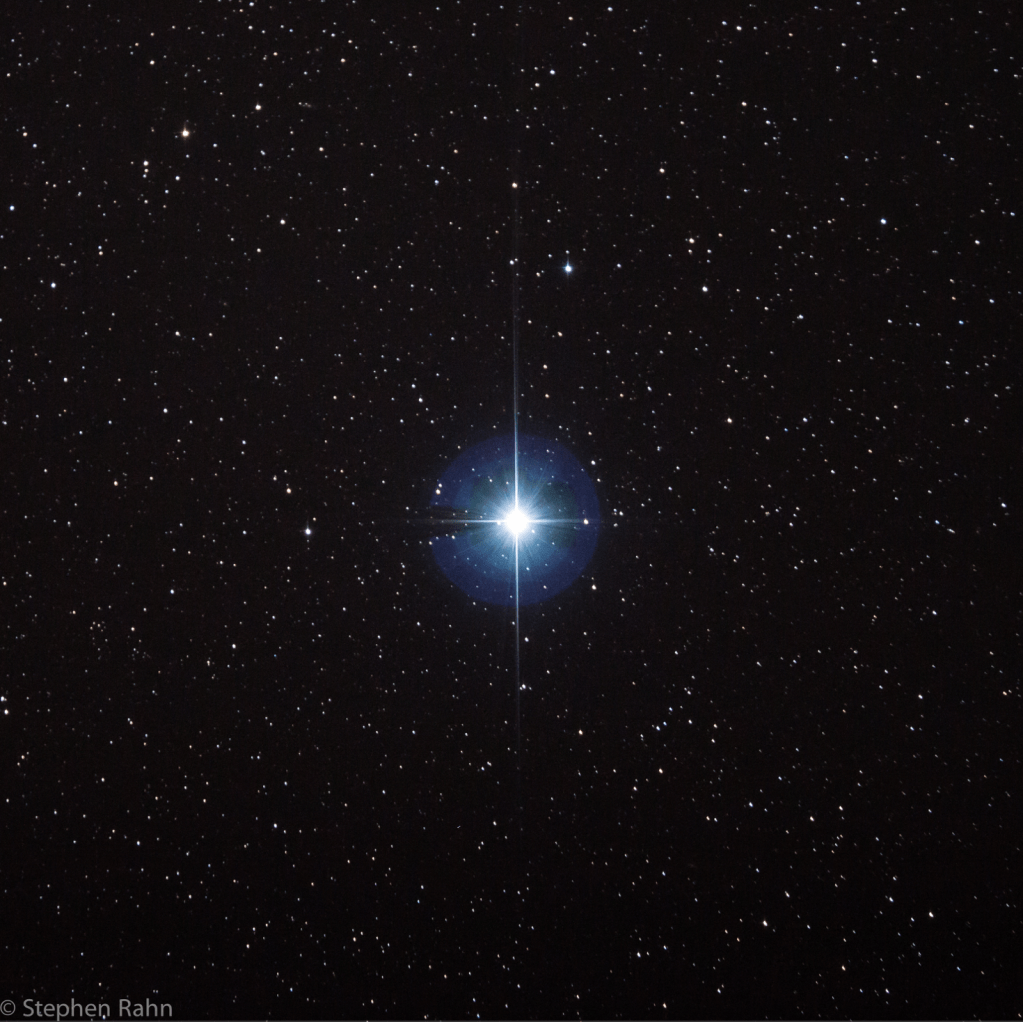

This, dear Reader, is a human experience of the Divine, of something greater than ourselves. I’ve long pondered how best to express my own beliefs concerning these questions, how best to refer to God. Dante sees God as a light emanating from the core of all things, and in my best effort at understanding the inherent paradox of God, for nearly a decade now I’ve come to think of a Divine Essence, as the best metaphysical expression of the Tetragrammaton which in its best English translation is rendered I am that Am. The Latin infinitive of the copula verb is essere, and this is the root of the noun essentia, so it seems prudent to me to write then of this Divine Essence, even if that Essence may seem impersonal. That’s where the three persons in one of the Trinity comes into my own faith.

At the end of Canto 22, Beatrice offers one of her last encouragements to Dante, the man who had loved her since first he saw her when they were children:

“’You are so close,’ Beatrice said,

‘to your salvation here that you must keep

the light within your eye acute and clear.

And so, before you further ‘in’ yourself,

look down and wonder at how great a world

already you have set beneath your feet,

so that your heart may show itself, as full

as it may be, to this triumphant throng

that rings in happiness the ethereal round.’”[14]

Dante here has a moment to look down on the Earth, on his home, what the great humanist astrophysicist Carl Sagan called the Pale Blue Dot and admire just “how small and cheap it seemed.”[15] I admire how Dante is able to imagine the Earth in one view, to see our entire planet as one common body made up of many separate parts.

Dante’s Paradiso concludes the three cantiche of his Divine Comedy, one of the great works of epic poetry in the western canon. It offers many things to many people; to my medievalist friends it is a window into the cosmology and theology of an Italian at the dawn of the fourteenth century. I would add here my own question of how different this Commedià would be had it been written just a few decades later when the Black Death swept across Europe in the 1340s? To the believer today, it evokes a vision of the afterlife in all its nuance and promises what might become of us once our lives have ended and our souls are weighed for their actions and deeds while living. I see both of these visions in the Commedià and also a poet, someone with whom I share the vocation to craft stories and enrich the human experience with our words, trying to make sense of his own life in exile far from his beloved Florence.

Reading this work has enriched my experience of Dante and reawakened some of that spirit of imagination and faith which I’ve long sheltered from the harsh winds and tempests of these recent verses that I’ve written in the last few years of my life. As much as I look forward to that great garden party in my vision of Tír na nÓg, Dante’s celestial spheres leave me with a warm sense of hope for something better to come.

[1] Dante, Paradiso 5.66–67.

[2] Dante, Paradiso 15.88–89.

[3] Dante, Paradiso 16.22–24.

[4] Dante, Paradiso 16.43.

[5] Dante, Paradiso 18.55–57.

[6] Dante, Paradiso 19.70–78.

[7] Dante, Paradiso 20.13–15.

[8] Dante, Paradiso 21.4–12.

[9] Ovid, Metamorphoses 3.253–86.

[10] Dante, Paradiso 21.73–75.

[11] Dante, Paradiso 21.70–71.

[12] Dante, Paradiso 22.1–9.

[13] Exodus 3:6.

[14] Dante, Paradiso 22.124–132.

[15] Dante, Paradiso 22.135.