The Power of Personality – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

Next week, I will be teaching about the Era of Good Feelings and the elections of the 1820s which saw the rise of the Second Party System in my Eighth Grade United States History classes. The Era of Good Feelings was a period of political transition between the two-party politics of the Early Republic between the Jeffersonian Democratic-Republicans and the Federalists led by Alexander Hamilton and John Adams towards the Democratic Party founded by Andrew Jackson and the Whigs founded by remnant Federalists and anti-Jacksonians. This era is so named because it saw one major political party, the Democratic-Republicans, dominate American politics after the decline of the Federalists after the War of 1812. The President of the late 1810s and early 1820s, James Monroe, and his successor John Quincy Adams sought to ensure party politics would never return, yet those hopes soon proved futile.

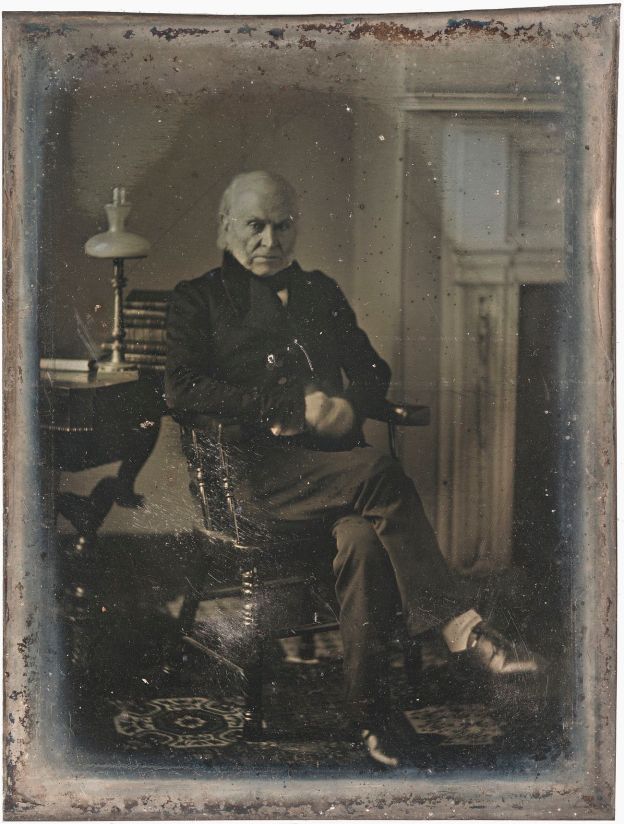

I’ve long enjoyed reading about John Quincy Adams, the eldest son of the second President, John Adams. The younger Adams had many qualities that I admire in a public servant: a great intellectual talent, a Ciceronian love of rhetoric, the patience of a great diplomat, and an openness to change for the benefit of new ideas. Adams was an early abolitionist and supporter of women’s suffrage fifty years before the passage of the 13th Amendment and a century before the 19th Amendment became law. Adams even tried to found a national university and a national observatory, as well as get the United States to adopt the metric system.

Sadly, none of these things happened during his administration, which ended in failure when his old political rival of 1824, General Andrew Jackson, returned with a populist fervor that elevated the Tennessee planter to the Presidency in 1828. This week as I’ve been making my slides for next week, I’m struck by the clarity of choices in the Election of 1828, and how those choices were between an incumbent who ran on policy and a firebrand outsider who ran on personality. It’s a familiar election narrative, yet it provoked a new conclusion about our current political stalemate between 2023’s Democrats and Republicans than what I had considered before.

Whereas the far-right of the Republican Party has a loud and defiant outsider candidate to rally behind to promote their vision of America, no other faction in either the Republican or Democratic Parties have the same kind of clear leadership. The parties are in a moment when few unifying voices can be heard, when there is always something about the current roster of politicians that leaves more voters choosing between “the lesser of two evils” rather than for a candidate they genuinely like.

Now, I’m biased in this monologue that I’m writing this week: I would have gladly voted to reelect John Quincy Adams in 1828, and not just because I don’t care for Andrew Jackson. Adams is one of my favorite presidents for all the reasons I included above; and his status as one of the fathers of the Whig Party, a preeminent predecessor of the modern Republican Party, shows how party philosophy changes with each successive generation. Still, while many in his day and now might discount the idea that John Quincy Adams had a strong political personality, I suggest we look to the politics of the early republic to find a guide out of our current quagmire.

Having a political figure who can unite a broad coalition behind their own banner, someone who is well liked by a majority of the voting public, is a way to move out of a period of uncertainty and nigh political chaos into a restored stability. The recent political history of the United States has elevated some who could fit this model, yet the extreme levels of bile flung by one faction at another leaves any sense of partisan unity, or better yet partisan magnanimity, far from certain. This leader should be able to bring this wide coalition together yet be humble enough to practice servant leadership, and remember they are in their role as President to help and guide the American people.

The great challenge of our time is to find a common purpose where we have long seen what divides us. It is a challenge which I know we can overcome, a hope which I believe we can realize.