Civic Pride – Wednesday Blog by Seán Thomas Kane

In a week of great triumph for my city and impactful announcements, some words on civic pride.

A city is as vibrant as the people who make it, and those who build on its strong foundations do well to recognize their forebearers. Cities are at the core of our concept of civilization, the city is the star about which a system of suburbs, exurbs, and ever more distant rural communities revolve. This has been true since antiquity, when the first human settlements were established for the mutual benefit of those who lived within them. Our cities today exist for similar reasons. It’s easier to live close to the places you work, eat, and play. It’s safer to live surrounded by like-minded people who in the best of circumstances will come together when a crisis emerges.

Cities are extensions of humanity; they can be organic in how they grow and function. The cancer and rot we’ve seen grow in our bodies that pose the greatest medical struggles today, mirrors the decay we’ve see in our cities in the last 70 years with urban renewal projects that removed vibrant urban life for new modes of living which prioritized distant suburbs and cars traveling far faster than one can walk in order to better connect our sprawl.

Our cities can find common passions in their livelihoods, civic pride in the things a city is known for making, and within the last 170 years in our professional sports. A central part of my love for my original hometown of Chicago comes from my memories as young boy in the suburbs of that city during the Bulls’ historic second threepeat and the Cubs wonderous 1998 season. Here in Kansas City the passion for our local teams, the Chiefs, Royals, Sporting, and the Current, is one common bond that runs throughout this city and its metropolitan region. We may agree on little else, but Kansas Citians agree on their passion for their teams.

This week then, Kansas City finds itself amid two pivotal moments in its recent history. On Sunday night the Kansas City Chiefs won their third Super Bowl in the last five years. This was also their second consecutive championship. As Quarterback Patrick Mahomes said in his post-game press conference, “the Kansas City Chiefs are never underdogs.” This success for the city’s football team remains in stark contrast to the Chiefs of my childhood. They made a playoff run during my first year living here, yet I remember listening to their early knockout defeat on the radio around New Year’s 2000. On the day that this is released, the Chiefs will parade down Grand Boulevard through Downtown & the Crossroads surrounded by what will surely be crowds of 1 million or more.

On Tuesday of this week, perhaps hoping to ride on the celebratory mood, the Kansas City Royals, this city’s Major League Baseball team, announced nearly 5 months late their choice for a new stadium site to replace the 52 year old Kauffman Stadium located next to the Chiefs’ Arrowhead Stadium in the eastern suburbs. In September of last year, the Royals had announced two preferred stadium sites, one on the east side of downtown along the east loop where Interstate 70 and US-71 round the urban core, and the other in North Kansas City across the Missouri River from Downtown in suburban Clay County.

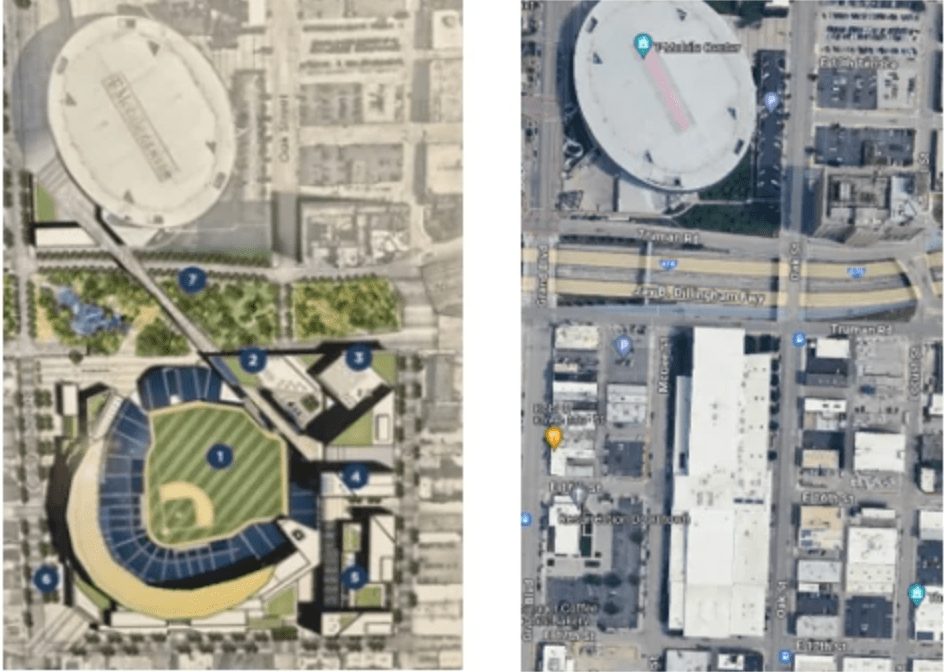

By the time the official announcement was released the rumors of what the announcement would hold had already been circulating for a good 12 hours, and to the bafflement of many, the delight of some, and the dismay of more the team announced they’d chosen a third site now occupied by the Kansas City Star Pavilion and a host of small businesses bounded by Truman Road on the north, Locust Street on the east, 17th Street on the south, and Grand Boulevard on the west. This site would be conveniently located next to the local indoor arena, the T-Mobile Center, where Kansas City’s hypothetical professional basketball and hockey teams would play. The proposed stadium would also connect to a park that is in the planning to be built over Interstate 670 on the south loop, which would continue to run beneath the park and new stadium.

A city needs to balance the causes of all of its constituents, each organ working in its own manner with minimal conflict between them. The proposed site of this stadium brings out clear and obvious conflict with local small businesses, Crossroads neighborhood residents, and the transportation grid of this city. I support the south loop park project which would cover Interstate 670 and better connect the Crossroads with Downtown, yet by that proposal Walnut Street and Grand Boulevard would be blocked by the park, which was fine before a baseball stadium was proposed to go there. The stadium proposal blocks Oak Street, a vital, if less used artery which runs along the east side of Downtown and the Crossroads connecting to Gillham Road in Midtown and eventually Rockhill Road at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art and Holmes Road on the east side of Brookside, my neighborhood.

The proposed stadium also displaces many vibrant local businesses that are located within its proposed footprint and will likely displace further local businesses in the surrounding blocks with a large new stadium dropped in the middle of their neighborhood. To me, it seems as though the team went out of its way to choose a third option which would disrupt as much of this city’s urban life as possible. With that in mind, I’m inclined to vote no on the question of whether we, Jackson County residents should renew the 3/8th-cent sales tax that’s on our April ballot in order to keep the Royals from building a stadium at this site.

Yet, I’m not opposed to a downtown stadium. I’m merely opposed to this proposed final location for the downtown stadium. I would prefer the City of Kansas City include questions on the April ballot asking municipal residents whether we’d prefer this location or the location on the east side of Downtown, which was the team’s original preference in Kansas City, Missouri. That location is currently occupied by parking lots rather than local businesses. It won’t require the demolition of a few vibrant blocks of urban life like the Crossroads location would. The one downside to the eastern location is that it is further away from the Streetcar line, the Power and Light District, and the T-Mobile Center. Yet spectators attending games at the current stadium walk further as it is often than they would in that situation.

At the end of it all, considering the history of teams that do not get their way with public funding for new stadiums, I worry that the current ballot question will not serve local residents in the best way possible. We stand to lose a great deal if the 3/8th-cent ballot question doesn’t pass, as both the Royals and the Chiefs have signaled their intent to look beyond Jackson County for new homes without that funding. While I expect the Chiefs to stay in Kansas City, I have my doubts about the Royals.

While all this is going on here, back in Chicago the White Sox and Bears organizations are also pressuring the City of Chicago and suburban municipalities for options for new stadiums as well. The Bears were all set on a northwestern suburban location in Arlington Heights until new pressures there have led them within the last week to muse about demolishing historic Soldier Field in favor of a new stadium in the old one’s southern parking lot along Burnham Harbor. Meanwhile, last week the White Sox released designs for a new stadium located 1 mile west of Soldier Field at an empty lot between Clark Street to the east, the South Branch of the Chicago River to the west, Roosevelt Road to the north, and 16th Street to the south. Over the summer when the White Sox initially found lukewarm reception for their own stadium rebuild, their leadership mused about either leaving Chicago for the suburbs or even going to Nashville.

My worry about the Royals, then, is that if they don’t get their way with the City of Kansas City, they’ll either move to North Kansas City, which would be all right but not ideal in my book, or worse out of town all together to a booming market like Nashville, Portland, or Austin. This city is proud of its teams, proud of its people, and proud of its local character. Let’s have clearer communication between all the parties involved in as momentous a decision as this new Royals Stadium as we can.I want to see a downtown stadium, just not on the site being proposed. One piece of the report from KCURthat bugged me more than others was that the Royals were unconcerned about the parking situation around their proposed stadium in the Crossroads because “as existing parking downtown can accommodate fans who drive to games.” This says to me they see all the expansive parking lots that remain in the Crossroads as permanent features of the area, and not temporary eyesores from a time when we thought it good to carve out our urban cores for the sake of suburban development. It says to me that the Royals organization wants to operate in the urban core but not be a part of the community.

Following Up

I write these blog posts on Mondays and Tuesdays, and after writing this one yesterday afternoon I’ve since read more about the project. To put it simply: I don’t know what I think about this project. One glaring issue I still have is that Royals organization has a website for their new stadium but I couldn’t find it on Google. Rather, I found it linked in a Reddit post. All of the information I have comes from KCUR, KSHB, KCTV-5, and the Kansas City Star, as well as other individuals on Reddit and X (formerly Twitter). One Reddit user posted a side-by-side comparison of the proposed stadium and the current site.

I’m still disappointed that the Royals are choosing a site that is presently occupied, and that in their FAQ they rely on current surface parking lots that dot the Crossroads for future game-day parking when we should be looking at redeveloping those lots and building garages to handle downtown parking.

Yet, I drove through this area yesterday evening on the way to a Fat Tuesday party, and I can see how they could make this site work. I still have many reservations about this project, but this morning, I don’t oppose it. I’m not issuing a retraction for several reasons: my original argument still stands on some of these issues, the podcast was already published at midnight, and I don’t have a backup plan. If anything, I want to make it clear how there are benefits and detriments to this plan. I wish the Royals site would acknowledge the impact their plan will have by closing Oak Street and displacing the businesses on the 1600 and 1700 blocks of Walnut, McGee, and Oak Streets, and again I wish they would discuss building more compact parking options than the swaths of surface parking that remains a blemish on our urban core.

I’m not happy about this blog post because I want to offer you a clear argument. Yet in this instance I’m not sure I can, there are too many factors involved. If we were looking at a spectrum with 0 as complete opposition and 100 as complete support, when I wrote the original blog post on Tuesday afternoon I was at a 35 or 40, still opposed to this project but not vehemently so. Now, I’m closer to a 55 or 60, supportive of it yet still quite cautious about what it could hold for our city.