On Sunday, I went with my parents to see the Immersive Van Gogh exhibit that’s been touring around the globe for the past few years. I first heard about it when I was in Paris in May 2018 and thought about going to see it there but ended up not paying a visit to it then. So, the following year when it was announced that Immersive Van Gogh would be coming to Kansas City, I jumped on the opportunity and bought tickets for my family to attend.

Then the world changed in what now seems like a prolonged moment as the COVID-19 Pandemic took hold around the globe. The exhibit opening was delayed in Kansas City, and it began to slip from my mind for the next couple years as the storms that shadowed the last few years of the 2010s burst into the troubled times that have been the hallmarks of the 2020s thus far.

So, after years of anticipation when I finally entered the Immersive Van Gogh exhibit this past Sunday afternoon I was awed to experience it, the sights and sounds combined for a truly awe-inspiring experience. We entered the gallery as Edith Piaf’s “Je ne regrette rien” burst over the speakers to the bright yellow hues of the fields of Provence as observed 140 years ago by the artist’s eyes. I took a seat on the floor with my back to a mirror-covered pillar and watched as the images danced across the walls and floor surrounding me.

The exhibit inspired a question: does our art influence how we perceive the world around us, and as a historian more importantly does the art of past generations influence how we today perceive the light and color and nature of past periods? Take the Belle-Époque, the age of the Impressionists like Monet and Post-Impressionists like Van Gogh, do we understand and think of the daily reality of that period in a way that is colored by the works of those artists? There is a Monet painting in the Nelson-Atkins French collection here in Kansas City of the Boulevard des Capucines which dates to 1873. It shows the hustle and bustle of the French capital in a manner that is both of its own time and seemingly timeless in how modern it appears. This extends in my own mind to the point that I’ve imagined the same scene whenever I’ve happened to walk down that same boulevard in the last few years.

On the other hand, the images that exist of Kansas City from the nineteenth century are largely dominated by black-and-white photographs and the odd painting by the likes of our first great local artist George Caleb Bingham (1811–1879). So, for how many of us are our ideas of say the Civil War largely just in black and white even though the reality was in the same vibrant color as we see now today? Even in my own life, I’ve found that there’s a slight hint of faded color in my memories of earliest days of my life, perhaps influenced by the technology available in the color photography of the 1990s which is noticeably less radiant than the colors available today in our digital images.

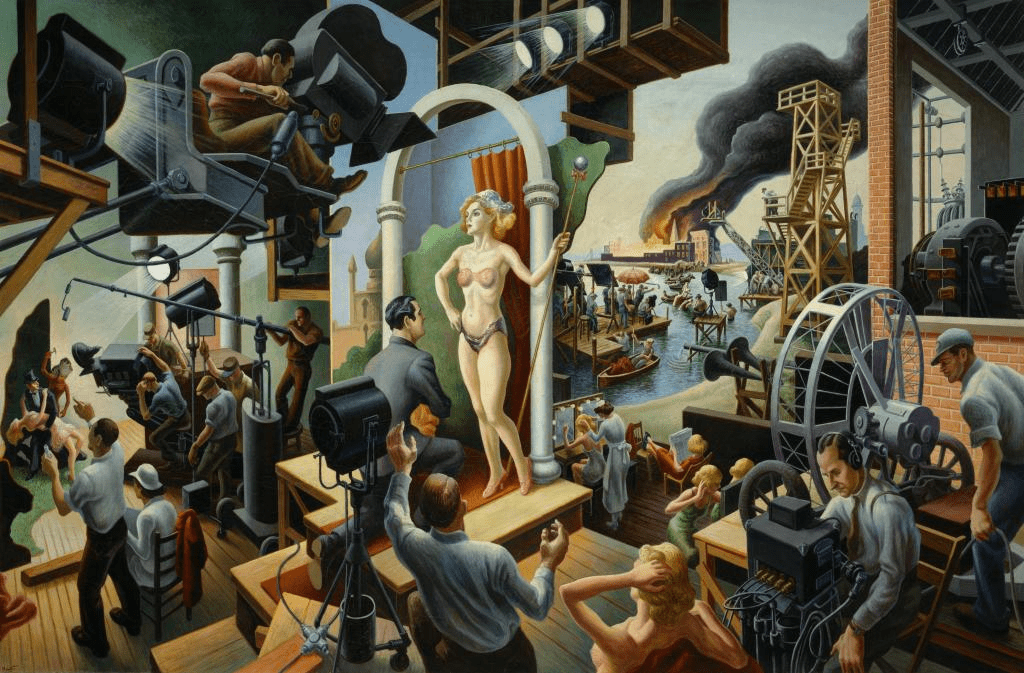

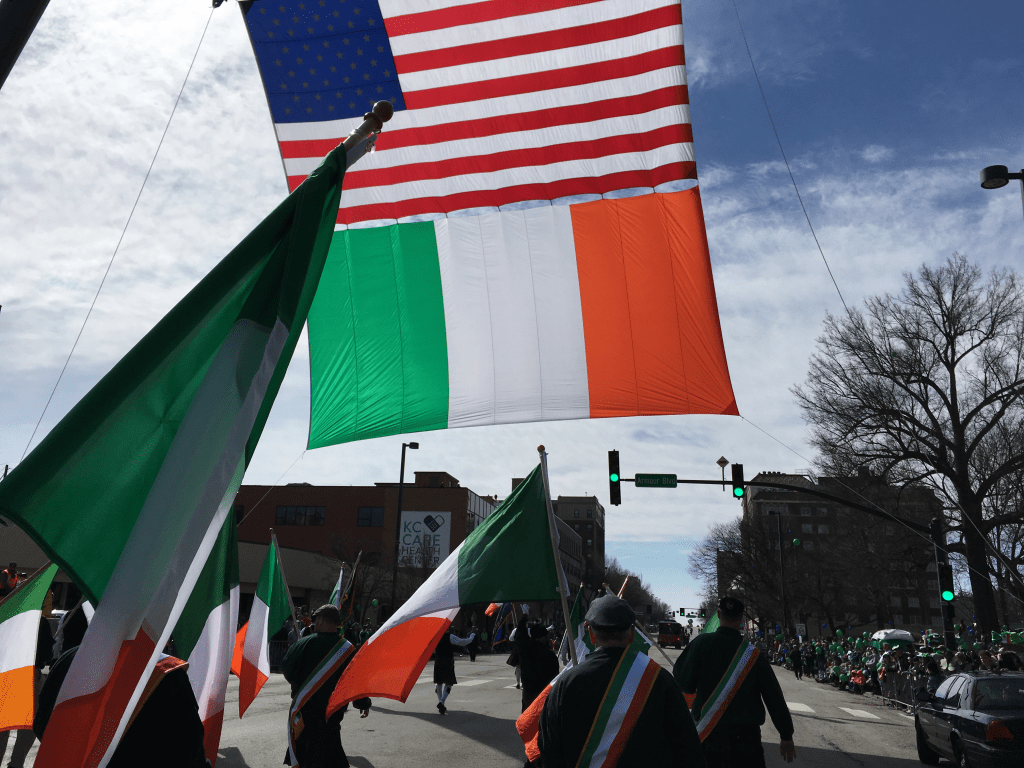

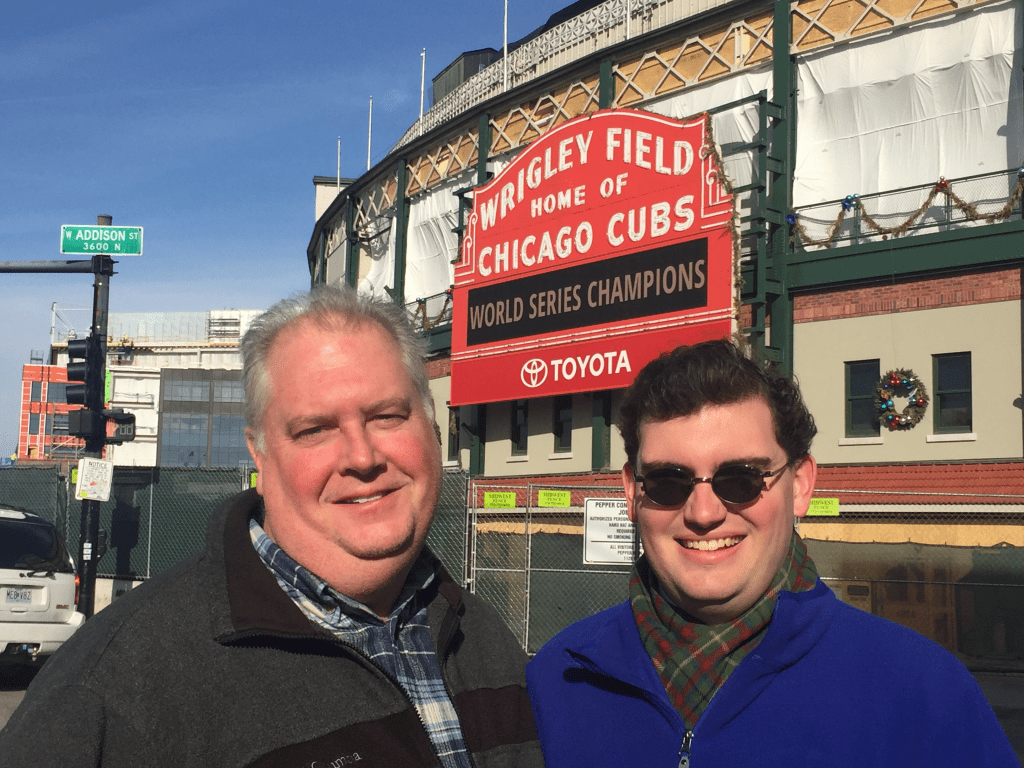

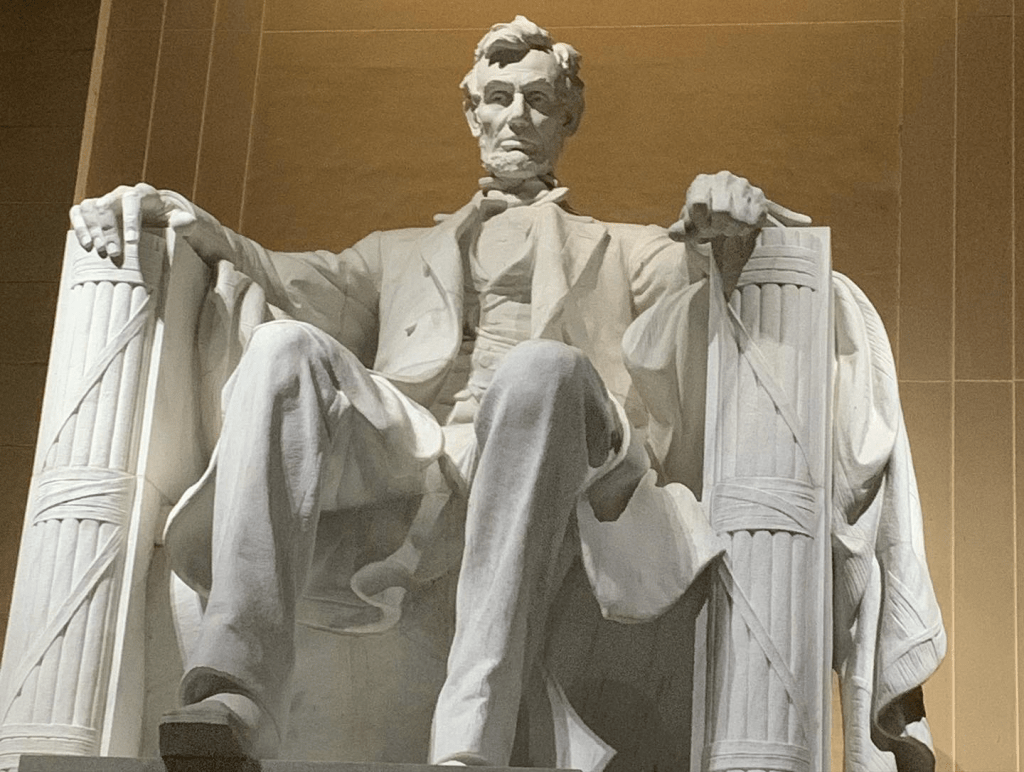

Art at its most fundamental level is a means of communication. It transmits memories from the creator, a historian of their own sort, to their patrons in posterity. Whether that art is expressed in painting or sculpture, sketching or cartoons, music or poetry, theatre or film, and in every form of literature both fiction and non-fiction alike, it is still at its core a transmission of knowledge and information. Through art the dead are able to speak to us still. In art we can experience something of the world that others live, that they see and hear and think. In the paintings of Thomas Hart Benton (1889–1975), in my opinion the greatest Kansas City artist to date, we can see echoes of American life as he understood it in the first half of the twentieth century. I can truly say that his art has influenced how I understood the Depression, World War II, and the Postwar years in a way that is best described by the fact that having grown up in Kansas City going to the Nelson and the Truman Library I saw his art far more often than many other Americans might well have. Through his paintings, Benton communicated ideas about what it means to be American, and the place of the Midwest in general and this part of Missouri in particular in the wider fabric of this diverse country of ours.

So, what sort of message will we in the 2020s leave for future generations? What do we want to communicate to them? In the last couple of weeks, I’ve been thinking of the Stephen Foster song “Hard Times Come Again No More.” Written in 1854 at a time when my home region was embroiled in the Border War known more commonly as Bleeding Kansas, one of the last preludes to the American Civil War of the 1860s, I’ve always thought of “Hard Times” as a song not of the nineteenth century but of the Great Depression, something that I could imagine being sung by farmers fleeing the Dust Bowl here in the prairies for new lives elsewhere. Still, the fact that the stories surrounding that song can speak to different times with common troubles speaks to the power of art. Maybe it’s high time we restore “Hard Times” to the charts, after all what better description of the present could there possibly be?